Insect Dogfights: How Aerial Combat Shapes the Patterns of Insect Flight

We might think insects use flight as simply a way to get form A to B. However, along the way they will fly through a congested airspace. In flight, insects battle for prey, territory, and mate, performing dramatic aerial dogfights. This presentation will discuss the patterns of insect aerial pursuit and combat, through the use of 3D reconstruction of high-speed aerial engagements.

Q&A with Dr Samuel T. Fabian

Dr Samuel T. Fabian is a research associate at Imperial College London. His work focusses on the ways in which insects are adapted to chase, fight, and capture each other in the air. The goal of his work is to understand the patterns of insect flight we see around us.

Why do the houseflies do territorial dances under lampshades?

It’s a great question that I don’t have an answer to. It’s something you see all over the world. The particular species that I spoke about, Fannia canicularis, probably started its evolutionary trajectory being in caves, specifically on bat guano or bird poo but why they are so interested in some visual fixture in the ceiling is a very good question. This behaviour, in some way, must increase their access to females. Its relatively common in nature for males to congregate and fight over areas where females are likely to occur. Hill-topping behaviour in butterflies is a good example. But why female houseflies would be likely to be interested in a lampshade is as yet, a mystery. It’s a really good question and it’s such a weird thing for males to do, to spend what days you have on earth, just travelling in circles under a lampshade.

How dangerous are flight interactions between insects of the same species?

I’ve talked about these chases as though they’re life and death situations, and for your predator/prey interactions, it is. But when we are talking about territorial conflicts, it varies. Sometimes, these insects really mess each other up. Demoiselles (Calopteryx sp.) are damselflies found in river habitats and will grab each other’s wings, bite each other and drive each other towards the water. However, in many flying insects it’s much less clear that they possess any way of damaging each other. For instance, with the dragonfly Trithemis aurora, they mostly just fly around each other. In the 500 or so recordings that I have of them dogfighting, not once do they touch. So, it’s a threat that doesn’t materialise into actual physical damage. You could think of it as being a ritualised conflict.

Do you see a lot of variation between different species of insects in how aggressive the flight interactions are?

Yes, there are a lot of differences. Another form of chasing is intraspecific conflict over territory. Some butterflies and dragonflies are aggressive not just towards members of their species but also towards any other members of their group. For instance, peacock and tortoiseshell butterflies chase and battle each other in the early spring, despite being different species. There are also very different behaviours when it comes to aggression. If you watch larger Emperor Dragonflies interacting, their behaviour is quite different to smaller dragonflies– they will actually smack into each other repeatedly. Some species of dragonflies will fly parallel to each other, holding themselves up in a vertical T-pose, defying gravity, and rising gently upwards until one loses and is chased away. There are likely many more interaction types waiting for formal recordings and descriptions, and there’s never been a better time to try and collect this data.

Literature References

- Fabian et al (2024) Fabian, S.T., Sondhi, Y., Allen, P.E. et al. Why flying insects gather at artificial light: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44785-3

- Fabian et al (2022) Avoiding obstacles while intercepting a moving target: a miniature fly’s solution: https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.243568

- Fabian et al (2021) Gravity and active acceleration limit the ability of killer flies (Coenosia attenuata) to steer towards prey when attacking from above: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2021.0058

- Fabian et al (2018) Interception by two predatory fly species is explained by a proportional navigation feedback controller: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsif.2018.0466

- Supple et al (2020) Binocular Encoding in the Damselfly Pre-motor Target Tracking System: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.031

- Wardill & Fabian et al (2017) A Novel Interception Strategy in a Miniature Robber Fly with Extreme Visual Acuity: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.050

- Gonzalez-Bellido et al (2016) Target detection in insects: optical, neural and behavioral optimizations: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2016.09.001

Further Info

- Sam’s website: https://www.samueltfabian.com/

- Damselflies of the UK entoLEARN course: https://courses.biologicalrecording.co.uk/courses/damselflies

- Dragonflies of the UK entoLEARN course: https://courses.biologicalrecording.co.uk/courses/dragonflies

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

Guardians of our Rivers: Monitoring Rivers with Freshwater Invertebrates

Freshwater invertebrates are powerful indicators of river health. Their presence, diversity, and sensitivity to pollution provide valuable insights into water quality and ecosystem stability. This talk will delve into the world of caddisflies, mayflies, stoneflies and freshwater shrimp – introducing these groups of invertebrate that inhabit our rivers and how they can be used to assess environmental changes, detect pollution, and guide river restoration efforts. We’ll then hear about how the Guardians of Rivers project is connecting communities with their rivers in Scotland.

Q&A with Kerry Dodd

Kerry Dodd is a Conservation Officer with Buglife Scotland and has been working on freshwater invertebrates for over 15 years. She works on the Guardian of Our Rivers project, where she enjoys surveying our rivers for invertebrates and inspiring communities to get involved in monitoring river health.

How long do the cased caddisfly larvae stay in their cases?

It depends on the family. Some make a new case at each instar (life stage), so that’s 5 cases. Some make their case larger as they grow. Glossomatidae sometimes leave their case if in still water and Microcaddis (Hydroptilidae) are caseless for the first four instars.

Do you do any chemical testing of rivers through Guardians of our Rivers?

Guardians of our Rivers monitors the health of rivers by surveying freshwater invertebrates. The freshwater invertebrates included in the survey are sensitive to water quality, stay in one place and most are found throughout the year. If there is dramatic decline in abundance across the groups, it suggests there is a problem with the water quality. It is unlikely to be due to seasonal variation or migration.

Chemical testing alone, may not pick up past pollution incidents as it gives a snapshot of the water quality at that moment. A decline in the abundance of invertebrates takes time to recover after the pollution has been washed downstream. Invertebrate surveys can pick detect past pollution incidents. However, chemical testing goes hand in hand with Guardians of our Rivers. We have groups that do the FreshWater Watch water testing (Nitrates, Phosphates and turbidity) each time they survey.

Do riverflies have any benefits to rivers aside from being prey items for other animals?

As well as being at the bottom of a complex a food chain, freshwater invertebrates help clean the watercourse. They feed by either breaking down organic matter such as plant material, detritus and algae or by filtering particles out of the water.

How can people get involved in riverfly monitoring across Great Britain?

If you are in Scotland, please email me at Kerry.dodd@buglife.org.uk to find your nearest Guardians of our Rivers group and upcoming training opportunities. In the rest of the UK, please contact The Riverfly Partnership at info@riverflies.org to find your nearest group and training opportunities.

Useful links

- Guardians of our Rivers project: https://www.buglife.org.uk/projects/guardians-of-our-rivers/

- Riverfly Partnership website: https://www.riverflies.org/

- Buglife Freshwater Hub: https://www.buglife.org.uk/resources/habitat-hub/freshwater-hub/

- The Hunt for the Northern February Red: https://www.buglife.org.uk/get-involved/surveys/the-hunt-for-the-northern-february-red/

- Guardians of our Rivers: Next Steps: https://www.buglife.org.uk/projects/guardians-of-our-rivers-next-steps/

- Riverflies: The Canary of Our Rivers entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2023/09/18/riverflies/

Event Partners

This blog was produced by the by the Biological Recording Company as part of the Tayside Biodiversity Partnership Biodiversity Towns, Villages and Neighbourhoods project.

Learn more about British wildlife

Beginner’s Guide to Creating a Wildlife Pond

Learn about the art and science of creating a wildlife pond, so that you can establish a thriving aquatic habitat that attracts diverse species of flora and fauna. We’ll explore the essentials, from selecting the ideal location and materials to designing a pond that supports a wide variety of wildlife, including amphibians, insects, and birds. Attendees will learn how to choose native plants, create safe access points for animals, and maintain water quality without disrupting the natural ecosystem. With an emphasis on biodiversity, the talk provides actionable steps and inspiration for anyone eager to transform their outdoor space into a vibrant habitat.

Q&A with Lauren Kennedy

Lauren Kennedy is the Engagement Officer for the British Dragonfly Society and happily admits to being obsessed with invertebrates and plants. She graduated in Biology at Cardiff University before going on to study a masters in Environmental Biology at Swansea University. Lauren has previously worked for Natural England, the Field Studies Council and Bumblebee Conservation Trust, whereshe focused on public engagement, working with volunteers and creating training.

What is the ideal depth for a wildlife pond?

You want your wildlife pond to have gently sloping sides, getting gradually deeper toward the centre. If it is possible to have a depth of at least 60cm at the centre this will increase the oxygen available in the water and will also help to safe guard your pond from freezing over in the winter. Many invertebrates, including dragonfly larvae, will be overwintering in your pond so we don’t want them to freeze! Take a look at our full pond creation guide for more detailed information.

How do you avoid attracting too many mosquitoes to a garden pond?

Unfortunately, mosquitoes, to a certain extent, will be a natural part of your pond ecosystem. However, with a garden pond, when you create the ideal conditions to support a variety of wildlife you will be inviting in the natural predators of mosquitoes. Setting up your variety of plants, and structuring your pond for wildlife will bring in plenty of dragonflies and they love to feast on small insects like mosquitoes.

Why is autumn the best time to undertake pond maintenance?

Autumn and winter is the least disruptive time to undertake any pond maintenance. Wildlife is far less active at this time so you won’t be disturbing key parts of their life cycle. Dragonflies for example spend the spring and summer emerging from the water leaving their larval forms behind and emerging as adults. These adults will then go on to mate and lay eggs in your pond, thus a busy time. There will still be plenty of aquatic life in your pond during the autumn and winter so remember to leave any pond material that you are clearing out on the side of the pond for a couple of days to allow any pond life to crawl back into the water.

How can people get involved with monitoring dragonflies?

We would love to hear what species you are finding visiting your garden pond, and your sightings could help inform vital conservation work and help us map how dragonfly populations are changing in the face of climate change. For identification help you can find lots of ID resources on our website and you can submit records of dragonflies through our iRecord form.

Useful links

- British Dragonfly Society Garden and Habitat Management: https://british-dragonflies.org.uk/get-involved/resources/habitat-management-and-species-guidebooks/

- Damselflies of the UK entoLEARN course: https://courses.biologicalrecording.co.uk/courses/damselflies

- Freshwater Leeches of the UK entoLEARN course: https://courses.biologicalrecording.co.uk/courses/freshwater-leeches

- Dragonflies of the UK Part 2 entoLEARN webinar: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/dragonflies-of-the-uk-part-2-tickets-1107775358919

- Dragonflies of the UK Part 3 webinar: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/dragonflies-of-the-uk-part-3-tickets-1108051785719

- Dragonfly ID help: https://british-dragonflies.org.uk/odonata/species-and-identification/

- DragonflyWatch: The National Dragonfly Recording Scheme entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2023/04/27/dragonflywatch/

- Record dragonflies and damselflies on iRecord: https://irecord.org.uk/enter-dragonfly-list

Event Partners

This blog was produced by the by the Biological Recording Company as part of the Tayside Biodiversity Partnership Biodiversity Towns, Villages and Neighbourhoods project.

Learn more about British wildlife

Microplastic Pollution and Solutions

An estimated 12.7 million tonnes of microplastics enter the environment annually. Most of this pollution is emitted to land, yet we find microplastics in all parts of the environment, even in the deep ocean. How are the microplastics distributed and transported? What impacts do they have on the environment? And can alternative plastics, such as those that are biodegradable, offer solutions to the plastic crisis?

Q&A with Dr Winnie Courtene-Jones

Dr Winnie Courtene-Jones is a lecturer at Bangor University; a marine biologist and microplastic pollution expert whose research focuses on understanding the fate and impacts of (micro)plastics to support effective solutions. Her research has led her to study microplastic pollution in a variety of terrestrial and marine environments, from coastlines to some of the most remote parts of our planet including the deep sea and oceanic gyres. A passionate science communicator, Winnie has been featured on TV, radio, and podcasts. She is an active member of the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, supporting progress towards the development of a legally binding instrument, and has spoken at these UN negotiations, along with the British and the European Parliaments.

Is buying recycled plastic products worse for the environment than buying non-plastic products?

That is a tricky question and I don’t know if I could say better or worse because there are so many aspects to understand and evaluate. What we do have to think about is that recycled plastic might have, potentially, more chemicals added into it. Not only do you have chemical residues from the plastic itself and from the recycling process, there are also specific chemicals added by the manufacturers to form the new product. For example, there are regulations preventing recycled plastics for food contact materials.

From your initial research, do you know what the bioavailability is and how it varies between the biobased and the conventional oil-based plastics?

Bioavailability, in terms of how an organism might ingest it, is another area that requires more research. To my knowledge, there haven’t been studies into whether animals have a preference for interacting with one type of plastic over another. Small plastics (microplastics) are more readily available for organisms to ingest, than larger particle sizes.

If we think about toxicity, there is evidence that there are similar, or possibly greater, impacts with biobased materials. Some work I led examined biobased textiles and their effect on earthworms and found that biobased fibres had a greater impact (on terms of mortality) across a broad concentration range, than the traditional polyester textiles. It’s not altogether clear why this is the case, and we need further research on this. Biodegradable plastics can contain more additives because the plastic can’t biodegrade too quickly- it must carry out its full function before biodegrading. It’s quite complicated and we don’t have all the parts of the puzzle in place yet.

Are there any brands of teabags that are worse than others?

I use loose leaf tea. Again, it’s complex to say which brands are better, but generally, teabags need a certain temperature to compost properly. If you compost them at home, they will not degrade properly,.they needs a heat of at least 60 degrees Celsius for the plastic (PLA – polyactic acid) to commence deteriorating. Often, the packaging does not explain how to properly dispose of your teabags, and this might be further complicated by wether or not you have industrial composting facilities available on your county/district.

Do you think it is possible for humans to ever be plastic free?

I don’t think we will be plastic free nor do I necessarily advocate for that. plastic is a sophisticated material, with use in specific applications. Reducing plastic use, simplifying materials by reducing the number of chemicals used in plastics, implementing regulations on production and limiting single use or disposable items are all ways to reduce negative impacts, and thus an overall reduction of the quantities that we find in the environment. Let’s change that 460 million tonnes of plastics produced annually to a much lower figure for the future!

Literature References

- Thompson et al (2024) Twenty years of microplastic pollution: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adl2746

- Courtene-Jones et al (2021) Source, sea and sink—A holistic approach to understanding plastic pollution in the Southern Caribbean: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S004896972104170X

- Courtene-Jones et al (2024) Are Biobased Microfibers Less Harmful than Conventional Plastic Microfibers: Evidence from Earthworms: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.4c05856

- Courtene-Jones et al (2024) Deterioration of bio-based polylactic acid plastic teabags under environmental conditions and their associated effects on earthworms: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004896972402953X

- Courtene-Jones e al (2024) Effect of biodegradable and conventional microplastic exposure in combination with seawater inundation on the coastal terrestrial plant Plantago coronopus: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749124012879

Further Info

- Info about Winnie: https://winniecourtenejones.wixsite.com/home

- Follow along with the UN Plastics Treaty: https://www.unep.org/inc-plastic-pollution

- Find out more about the Scientists Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty: https://ikhapp.org/scientist-about-us/

- Direct link to the free resources: https://ikhapp.org/materials/

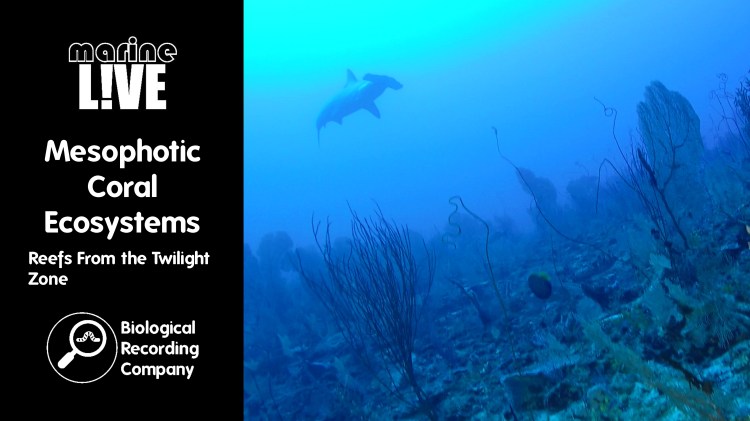

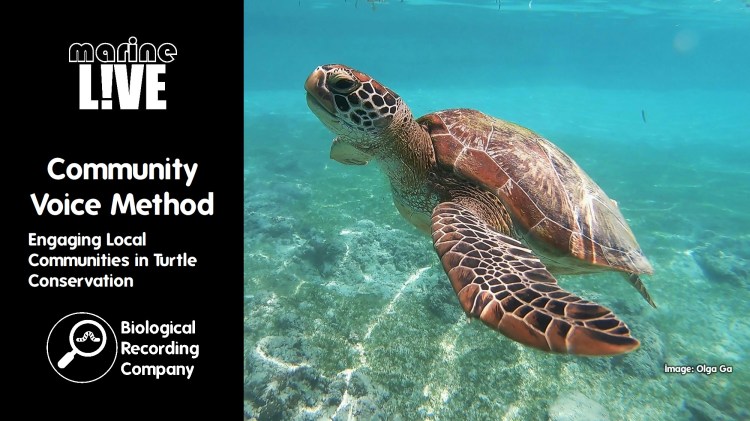

marineLIVE

marineLIVE webinars feature guest marine biologists talking about their research into the various organisms that inhabit our seas and oceans, and the threats that they face. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for marine life is all that’s required!

- Upcoming marineLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/cc/marinelive-webinars-3182319

- Donate to marineLIVE: https://gofund.me/fe084e0f

- marineLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/marinelive-blog/

- marineLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE-t2dzcoX59iR41WnEf21fg&feature=shared

marineLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company with funding from the British Ecological Society.

- Explore upcoming events and training opportunities from the Biological Recording Company: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/o/the-biological-recording-company-35982868173

- Check out the British Ecological Society website for more information on membership, events, publications and special interest groups: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/

More on marine biology

Glowing, Glowing, Gone? The Plight of the Glow-worm in Essex

The glow-worm Lampyris noctiluca (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) is thought to be declining in the United Kingdom. Yet, much of the evidence for this is anecdotal, with a shortage of standardised long-term data to investigate temporal changes in abundance. A long-term transect study from Essex has produced statistical evidence of a decline (75%) in glow-worm abundance since 2001. There is a clear signal of climate warming and drying effects on glow-worm numbers and of local site changes due to a lack of active scrub management. Conservation strategies that mitigate local population losses could be an essential buffer against climate-driven declines in south-east England.

Q&A with Dr Tim Gardiner

Dr Tim Gardiner is a children’s author, ecologist, editor, essayist, poet, songwriter and storyteller. His scientific papers, poetry and prose have been published all over the world.

How widespread are glow worms in the UK?

They’ve been recorded in many places in the UK. As you go further north, populations become more isolated (possibly due to climate). However, there are old records from the Isle of Skye where people were seeing thousands. It’s on the west coast, so a bit milder there. You can check the distribution records on the Glow-worm (Lampyris noctiluca) NBN Atlas page. You can submit your records through the Glow-worm iRecord form. The thing with distribution maps is that they only show where the recorders are and an absence of records doesn’t necessarily mean that the species isn’t there. This is where people can make a real difference – we need more people looking in the places where there are gaps, seeing if they are there and submitting records.

What kinds of numbers would indicate a healthy and sustainable glow worm population?

If you’ve seen about 40, that’s a good population, but even 20 to 30 is a decent number. Whether that’s a viable population is another question. How big does a population need to be to be completely viable in the long term? It’s definitely double figures with at regular counts of numbers in the 30s and 40s. Counts in the 100s appear to be a thing of the past. Ideally, the individuals should also be spread out rather than concentrated in a small area, to reduce the risk of someone mowing the whole lot, unintentionally destroying the population. This is where corridor habitats are important.

How successful is Glow-worm translocation?

It really is too early to tell. I’m not aware of any post-release data, and there certainly hasn’t been enough time elapsed to get any long-term data. There was a site, in south Essex, where they were moving reptiles and they discovered larvae at the same time so they also moved the Glow-worm population. In this instance, the larvae were translocated because otherwise they too would have been doomed – it wasn’t planned and it was not part of scheme to seed an area with Glow-worms. This was at least successful for a few years and there are still some glow worms in that area, but we need the accurate scientific monitoring of these translocations to be certain they work and they don’t jeopardise the population you take insects from. The people doing the translocations need to not only monitor but also to publish their results. And we need to talk about failure as much as success.

Is it known how far males will fly?

They don’t seem to fly that far; they stay quite local. One idea is that male and female larvae aggregate in certain areas and then the males and females are all there together. It makes mating a bit easier. Again, more research is needed.

Literature References

- Gardiner & Didham (2020) Glowing, glowing, gone? Monitoring long-term trends in glow-worm numbers in south-east England: https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12407

- Gardiner (2022) There Is a Light That Never Goes Out! Reversing the Glow-Worm’s Decline: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821139-7.00021-0

Further Info

- The UK Glow-worm Survey: https://www.glowworms.org.uk/

- Submit your records through the Glow-worm iRecord form: https://irecord.org.uk/enter-glow-worm-record

- Explore Glow-worm records on the NBN Atlas: https://species.nbnatlas.org/species/NBNSYS0000010994

- Reversing the Glow-Worm’s Decline article: https://www.notechmagazine.com/2021/04/reversing-the-glow-worms-decline.html

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

Amphibians

Amphibians are cold-blooded vertebrates that begin life breathing through gills in water and undergo metamorphosis to develop lungs for terrestrial living. The UK hosts seven native species of frogs, toads, and newts. This webinar will explore their life cycles and ecology, examine the threats they face, and discuss how we can support amphibians in our gardens and community spaces.

This blog features presentations from two amphibian specialists, that will explore the biology and ecology of these fascinating animals, before highlighting the threats that our amphibians face and what we can do to help them. This will be followed by an opportunity to put your amphibian-related questions to our panel!

Amphibians and their Ecology

Janet Ullman (Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Trust)

Discover the fascinating world of British amphibians, including frogs, toads, and newts. This presentation explores their unique life cycles, habitats and ecological roles. Join us to celebrate the unique role these creatures play in the natural balance of our ecosystems. Perfect for nature enthusiasts and conservation advocates alike!

Amphibian Threats and Conservation

Dr John Wilkinson (Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Trust)

Learn about the challenges facing British amphibians, including habitat loss, diseases, invasive species and roads. We’ll then explore the innovative conservation efforts aimed at safeguarding the future of our frogs, toads and newts, and highlight the importance of protecting these vital species and the steps we can all take to make a difference.

Q&A with Janet Ullman and Dr John Wilkinson

Janet Ullman is the Education Officer for Saving Scotland’s Amphibians and Reptiles (SSAAR) at the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust. SSAR aims to encourage a greater understanding of our amphibian and reptile populations and to protect, restore or create habitat features to allow our amphibians and reptiles to thrive in Scotland.

Dr John Wilkinson is a conservation ecologist who has been working with amphibians and reptiles for over 25 years. He manages Regional, Science and Training Programmes for the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust (ARC) and has a particular fascination for toads! John has also authored the Amphibian Survey and Monitoring Handbook and a number of scientific articles and technical reports focusing on herpetology.

What do amphibians eat?

Janet: Live prey only, they are sensory killing machines. The frogs and toads have those super shooting-out tongues which adhere to prey that swim, crawl, wiggle or buzz by. It’s a wide menu of insects, spiders, woodlice, earthworms (sorry Keiron), small slugs, snails and even small amphibian larvae and metamorphs. It’s pretty much the same for newts but with added small crustaceans in water and voracious predators of frogspawn and tadpoles. Newts smell their prey, whereas frogs and toads are more movement and sight.

What are the main predators of froglets?

Janet: In my experience just about everything will wolf up a froglet, but birds will be on the watch for them as soon as they realise it is that time of year. I’ve watched the carnage of mass emergence when seagulls swooped in.

Can any of the non-native newt species hybridise with our native species?

John: “Our” great crested newts are closely-related to Italian crested newts and marbled newts, and they can hybridise. Studies have shown this does happen in the UK. The important thing is to monitor where non-natives turn up and what effects they may be having.

Should we be removing a build up of leaf litter from garden ponds?

John: Sometimes, yes. A small pond will eventually disappear without management. The best time to remove excess weed and dead leaves from your ponds is late Autumn – when there will be fewer creatures in it but those that are there haven’t yet hunkered down for hibernation. Leave anything you remove on the side of the pond for a few days so any creatures can crawl back in! Check out our Creating Garden Ponds for Wildlife guide for more advice.

Is it safe to move frogspawn from non-viable puddles to a pond?

Janet: I would advise yes as long as the pond chosen as a new home is as close as possible, within 1 km is best. Do think about if it is a healthy pond to relocate too, will it have enough prey items, is it full of predators such as fish and does it have the capacity to take more spawn?

Is pollution in SuDS (Sustainable drainage systems) ponds an issue for amphibians that may colonise them?

John: A variety of pollutants from our roads (including winter salt) can turn up in SuDS, though ideally (and if the scheme is well-designed) these are filtered out by reeds and rushes that should be part of it. In some circumstances amphibians can be affected, but this will vary by the design and location of the scheme. It’s worth noting that NO SuDS ponds means nowhere for amphibians to breed, so having those ponds has to be better than not!

What is the one thing that you’d recommend people can do to help our amphibians?

Janet: This is hard, surveying is important, but seeing amphibians in urban settings is a wonderful thing and is all due to gardens and public green spaces having the right mix of habitats, especially refugia for animals to hide in, over winter and find prey. Whether in town or the countryside, good habitat is key.

John: Not everyone is able to create a pond or other habitat on their property, but there may be local community garden or park schemes where you can get involved. Otherwise, consider being an ARC volunteer and recording/monitoring your local species to help inform the efforts for their conservation.

Useful links

- Water For Wildlife free webinar: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/water-for-wildlife-get-involved-with-water-conservation-tickets-1253217329769

- ARC’s Bitesize Herpetology Modules

- Identifying UK Frogs and Toads: https://www.arc-trust.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=0845fa8a-7e68-4e96-8c01-dcd39c63a0f8

- Identifying UK Newts: https://www.arc-trust.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=9c5fca7d-ab32-4f71-8cf8-5d4ca1a7a421

- Full list of modules: https://www.arc-trust.org/training

- Register as an ARC volunteer to take part in our monitoring or other volunteering: https://www.arc-trust.org/Listing/Category/volunteer

- Find out about our National Survey Programmes and projects: https://monitoring.arc-trust.org/

Amphibian conservation in Scotland

- Tayside Amphibian & Reptile Group: https://groups.arguk.org/tayarg

- Tayside ARG events: https://www.taysidebiodiversity.co.uk/2025/02/11/2025-tayarg-programme-of-events/

- The next Amphibian Ladder Workshop will be in Stanley (north of Perth) on 21st March. This will be led by Trevor Rose the inventor of the ladders and Daniele Muir of TayARG. Contact Daniele via taysidepondsproject@gmail.com for further information. The event is suitable for adults and older teens.

- ARC in Scotland: https://www.arc-trust.org/saving-scotlands-amphibians-and-reptiles

- School citizen science project for Scotland at https://www.arc-trust.org/champhibians

- Species on the Edge project: https://www.arc-trust.org/species-on-the-edge

Event Partners

This blog was produced by the by the Biological Recording Company as part of the Tayside Biodiversity Partnership Biodiversity Towns, Villages and Neighbourhoods project.

Learn more about British wildlife

The Mind of a Bee: An Exploration of the Intelligence of Bees

Most of us are aware of the hive mind—the power of bees as an amazing collective. But do we know how uniquely intelligent bees are as individuals? Lars Chittka draws from decades of research, including his own pioneering work, to argue that bees have remarkable cognitive abilities. He shows that they are profoundly smart, have distinct personalities, can recognize flowers and human faces, exhibit basic emotions, count, use simple tools, solve problems, and learn by observing others. They may even possess consciousness. Chittka illustrates how bee brains are unparalleled in the animal kingdom in terms of how much sophisticated material is packed into their tiny nervous systems. He looks at their innate behaviours and the ways their evolution as foragers may have contributed to their keen spatial memory. Chittka also examines the psychological differences between bees and the ethical dilemmas that arise in conservation and laboratory settings because bees might feel and think.

Q&A with Prof Lars Chittka

Lars Chittka is the author of the book The Mind of a Bee and Professor of Sensory and Behavioural Ecology at Queen Mary College of the University of London. He is also the founder of the Research Centre for Psychology at Queen Mary. He is known for his work on the evolution of sensory systems and cognition using insect-flower interactions as a model system. Chittka has made fundamental contributions to our understanding of animal cognition and its impact on evolutionary fitness by studying bumblebees and honeybees.

Do solitary bees show the same navigational ability and memory as the eusocial bees?

The challenges of spatial navigation for both solitary bees and social bees are similar. They both have to navigate often long distances away from the nest and reliably return to the nest. However, with a honeybee in a colony of 60,000 individuals, if it gets lost, it will die but the colony can compensate for that because there are lots of other workers that can take over. With solitary bees, if they don’t find their back to their nest, their offspring is likely going to perish as well. So there’s additional pressure. Also, solitary bee nests are often more hidden than social bee nests so that increases the challenge. But we don’t know much about solitary bees. There is a world of unknown biology that we should explore more.

Is there any difference in the learning between queens, workers and drones?

Male bees are famously lazy. They do not contribute to any work in the colony so people are often quite ready to dismiss them. But their learning is actually not that bad, especially in bumblebees. Males do their own flower foraging and so they also remember flower colours. They are, in fact, no worse than workers in associating colours with rewards and we can also teach them to pull strings just like we can with the workers. Bumblebee queens are basically ‘janes of all trades’. They have to visit flowers, build nests, defend the brood, warm the brood, forage etc. Their brains are very large and they are also very smart learners.

Honeybees are a little different. Honeybee drones can’t feed themselves; they rely on the workers to get fed. So, they don’t have to learn about the flowers. But if they fail to find a queen to mate with, they need to return to the colony, so they need spatial learning. Their brains are actually quite large, in part because their visual systems are huge – they have very large eyes that facilitate the detection of queens. Honeybee queens, who also don’t have to visit flowers, have relatively smaller brains compared to workers in proportion to their body sizes.

How long does it take to train the bees in the experiments?

Some tasks are very simple, like getting them to associate an attractive scent or a colour with a reward. Often two or three trials are enough for the bees to remember them for hours or even, sometimes, for days. Tasks like string pulling can take hours or days to train them. Interestingly, often with these types of tasks, the fastest way for them to learn is to observe skilled conspecifics. In this case, they sometimes get it right after just a single observation (although in many cases it takes a few more). It also depends quite strongly on the individual. So, for any task were testing, we’re finding that there are quite pronounced variations between individuals.

Is there any evidence that the nectar robbing behaviour by bumblebees involves social learning?

Long spurred flowers typically require long probosces for bees to get to the nectar. But some of the shorter-tongued bumblebees will actually find a shortcut by biting a hole into the spur and extracting the nectar without pollinating the flowers. Darwin thought that this bee behaviour spread via social learning. The first person who investigated this experimentally was my former PhD student, Elli Leadbeater who found that by default, most bees will visit the flowers in the regular way, but once a single individual figures out how to nectar rob, this technique spreads quite quickly through the colony via social learning.

Are bees able to pass on negative information to the rest of the colony?

In bumblebees, we don’t know. In honeybees, the answer is yes. There are specific signals that tell the colony what kind of danger to look out for. There are also so-called ‘stop signals’ that have been investigated by James Nieh and colleagues, Bees have this famous dance language where they can advertise the coordinates, precise distances and direction of a food source to a colony. But if there is a predator present there, another bee will headbutt the dancing bees and give brief vibration pulses that function as a stop signal to interrupt the dancers’ communication to alert them to the predation threat.

Literature References

- Chittka (2023) The Mind of a Bee: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691253893/the-mind-of-a-bee

- Gallo and Chittka (2018) Cognitive Aspects of Comb-Building in the Honeybee?: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00900/full

- Woodgate et al (2017) Continuous Radar Tracking Illustrates the Development of Multi-destination Routes of Bumblebees: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-17553-1

- Woodgate et al (2016) Life-Long Radar Tracking of Bumblebees: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0160333

- Alem et al (2016) Associative Mechanisms Allow for Social Learning and Cultural transmission of String Pulling in an Insect: https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1002564

- Loukola et al (2017) Bumblebees show cognitive flexibility by improving on an observed complex behavior: https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.aag2360?casa_token=F9goXuRm8iQAAAAA%3AA3V4MFgAIeaJOsMqiVpxLvykIBuEgH5cN2Hc5hAaZTDxcqeOGFmsrCJrcN2AraE4pVdcyZ_rY3spHA

- Solvi et al (2020) Bumblebees display cross-model object recognition between visual and tactile senses: https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.aay8064

- Dona et al (2022) Do bumblebees play?: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347222002366

- Ings & Chittka (2008) Speed-Accuracy Tradeoffs and False Alarms in Bee Responses to Cryptic Predators: https://www.cell.com/AJHG/fulltext/S0960-9822(08)01019-1

- Perry et al (2017) Studying emotion in invertebrates: what has been done, what can be measured and what they can provide): https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/220/21/3856/33729/Studying-emotion-in-invertebrates-what-has-been

- Maboudi et al (2017) Olfactory learning without the mushroom bodies: Spiking neural network models of the honeybee lateral antennal lobe tract reveal its capacities in odour memory tasks of varied complexities : https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005551

Further info

- Bumblebees of the UK online course: https://courses.biologicalrecording.co.uk/courses/bumblebees

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

More on bees

Make Your Garden Alive with Deadwood

Transform your garden into a thriving ecosystem by incorporating deadwood features. This blog highlights the vital role deadwood plays in supporting invertebrates and other wildlife. Learn practical ways to add and manage deadwood in your garden, creating a natural haven that benefits biodiversity while adding rustic charm to your outdoor space.

Q&A with Caitlin McLeod

Caitlin McLeod is a Conservation Officer for Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust. Caitlin works on the Species on the Edge programme, with a focus on the East Coast of Scotland and teaches volunteers to identify and survey rare invertebrates such as the Northern Brown Argus butterfly, Small Blue butterfly and Bordered Brown Lacewing.

Can old Christmas trees be used to create log piles?

Yes! Old Christmas trees can be cut up and added to log piles, though pine and other coniferous woods tend to decompose slowly compared to deciduous wood – though they can still provide habitats. You can cut off smaller branches to use as ground cover or for mulch, improving habitat for various ground-dwelling species.

Are all tree species good for deadwood?

Most tree species are a great addition to deadwood habitats, though it is better to use a variety of species rather than just one, and there are a few things to take into consideration such as using native species, such as oak, beech, ash and elm. Conifers can also be used though they tend to acidify the soil as they break down so it is important to take this into consideration! The most important thing is to avoid using treated wood as the chemicals can harm wildlife rather than help it.

Should you drill holes into deadwood to create access for invertebrates?

Drilling holes in deadwood features such as log piles can certainly help create access for invertebrates like solitary bees and beetles, especially if you create a variety of hole sizes and depths (2-10mm diameter and 2-10cm deep). Creating holes that will collect water is also a brilliant way to support many species of hoverflies whose larvae are aquatic (2-5cm in diameter and varying depths, in a shady spot).

Is there any point in leaving small pieces of deadwod in the garden?

Absolutely! Even a small, standalone piece of deadwood can play a crucial role in the survival of many species, at the end of the day it creates habitat no matter the size. Twigs, sticks and leaf litter create habitat for species like woodlice and other decomposers, as well as providing areas of moisture and shelter for amphibians, reptiles and other animals. Over time small pieces of deadwood will also break down and enrich the soil – smaller bits of wood will decompose quicker, promoting the growth of fungi, further benefitting soil health and supporting the broader ecosystem in your garden!

Useful links

- Create Your Own Deadwood Habitats: https://www.buglife.org.uk/get-involved/create-your-own-dead-wood-habitats/

- Dead Wood Piles for Beetles: https://cdn.buglife.org.uk/2022/09/Create-a-Dead-wood-pile-for-beetles.pdf

- Deadwood (Scottish Invertebrate Habitat Management): https://cdn.buglife.org.uk/2019/07/Deadwood_1.pdf

- Managing Dead and Decaying Wood Habitats (BFTB Habitat Management Guidance): https://cdn.buglife.org.uk/2022/01/BFTB-Advice-Sheet-Managing-Dead-and-Decaying-Wood.FINAL_.pdf

- Get involved with Buglife in Scotland: https://www.buglife.org.uk/get-involved/near-me/buglife-scotland/

- Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust: https://www.buglife.org.uk/

- Don’t Stop The Rot – Dead wood invertebrates and their conservation

Event Partners

This blog was produced by the by the Biological Recording Company as part of the Tayside Biodiversity Partnership Biodiversity Towns, Villages and Neighbourhoods project.

Learn more about British wildlife

Beginner’s Guide to Garden Bird Nest Boxes

Invite nature into your garden by providing safe nesting spaces for birds. This blog explores the importance of nest boxes, how to select the ideal one for different species, considering maintenance and where to position them for maximum success. Whether you’re a seasoned birdwatcher or new to wildlife gardening, you’ll leave with practical tips to make your outdoor space a bird-friendly sanctuary.

Q&A with Hazel McCambridge

Hazel McCambridge is the lead organiser of Nesting Neighbours at the British Trust for Ornithology and works on data collection and volunteer communication as Scheme Support Officer for several projects, including the BTO Acoustic Pipeline, the Ringing Scheme and the Nest Record Scheme. She is also BTO’s Sustainability Officer and author of the Blue Tit Diary.

Is it important to clean out nest boxes regularly to prevent the spread of disease?

For nest boxes it is good to take out the old nest during the winter (legally between September – January), making sure there is no active nesting. This reduces the parasite load which can hibernate over winter and rehome themselves on the chicks once they hatch in the nest. Nest boxes can also become full up with nesting material over the years. Disease isn’t spread in nest boxes in the same way that it is on bird feeders so regular / weekly cleaning is not required.

What considerations are needed when installing a nest box camera?

You can buy nest box kits which include cameras and are fairly simple to install. There are many other small cameras available on the market, you might want to consider if you can run a cable for a wired camera or if you need an unwired camera which can connect to wifi. Remember, it is dark in the box, so it also needs to be a camera with infrared night vision. I tend to avoid the nest boxes with a perspex wall which is used to allow light in for the camera, as you lose some of the important insulation of the box. Make sure to install the camera well ahead of the breeding season (end of Feb at the latest) and ensure it is fastened very securely.

How long should you leave an unused nest box before considering moving it?

If you have considered the guidance on placement (out of direct sunlight, rain, direct flight line to the entrance hole, predator avoidance measures, distance from feeders) and it hasn’t been used after about 3 years it is worth considering if another suitable location is available. We don’t always have options, so it is worth leaving it in place if you only have one location available – in my previous tiny garden I only had one suitable option and it was eventually used after 7 years!

What is your number one recommendation for supporting garden birds?

Particularly in urban and suburban locations, birds are losing nesting locations. We are insulating houses and tidying up old trees, so providing a nest box gives a suitable space for a pair of birds to raise their family. Find guidance on nest boxes and free building plans on the BTO website. You can then add even more value to this by monitoring the nesting activity and submitting the details to Nesting Neighbours, to help us understand how climate change and urbanisation are impacting nesting birds.

Useful links

- Join the BTO Garden BirdWatch for free: https://www.bto.org/our-science/projects/gbw

- Nesting Neighbours: www.bto.org/our-science/projects/nesting-neighbours

- Providing for birds: www.bto.org/how-you-can-help/providing-birds

- Nest box building: www.bto.org/how-you-can-help/providing-birds/putting-nest-boxes-birds/make-nest-box

- Purchase the book Nestboxes: Your complete guide: www.bto.org/our-science/publications/bto-books-and-guides/nestboxes-your-complete-guide

- British Trust for Ornithology (BTO): www.bto.org

Event Partners

This blog was produced by the by the Biological Recording Company as part of the Tayside Biodiversity Partnership Biodiversity Towns, Villages and Neighbourhoods project.