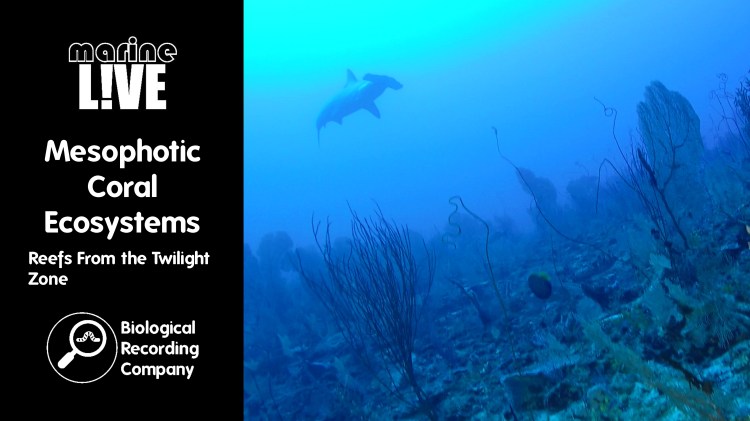

Mesophotic coral ecosystems, found roughly between 30m and 150m deep in tropical and subtropical areas, still remain poorly known. They’ve nonetheless been seen to be diverse and unique, harbouring numerous species; but are already threatened by climate change. This presentation will dive into the mysteries these ecosystems hold, including the tools being used to study them in the Chagos Archipelago, Indian Ocean.

This work was undertaken by Dr Clara Diaz with Dr Nicola Foster, Dr Phil Hosegood, Prof Kerry Howell, Dr Edward Robinson, Mr Peter Ganderton and Mr Adam Bolton from the University of Plymouth

Q&A with Dr Clara Diaz

Dr Clara Diaz is a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Plymouth investigating the ecology and resilience of mesophotic coral ecosystems

How can a reef be measured in dollars?

An ecosystem’s worth is measured by attributing economic services. For instance, coral reefs are very good at sheltering islands and coasts against waves and so it’s like an insurance that protects coasts from damage. Reefs also draw a lot of tourists, with diving activities especially. Another example is the profit from the fisheries, as the reef provides habitat and food for these commercially important fishes. An estimation of all these profits and costs are made to calculate the ecosystem service an ecosystem provides to humans.

Why do you think the corals recovered after the bleaching event?

This mass bleaching event we saw was due to the extreme deepening of the thermocline – the separation between cold and warm waters from a seasonal current. So the warm water, which is on top and in shallower waters, went very deep and stressed the coral (it was 29 degrees celsius at 100m deep!), causing this bleaching event, where the zooxanthellae (algae) were expelled from the corals. Fortunately, this warming event did not last for critically long, with the conditions coming back to normal afterwards, so the algae that had been released during the bleaching event came back to the coral. Some of the coral died unfortunately, but many survived. We were really pleased to see some of the coral recover and that they could recover after a bleaching event – if the conditions come back to normal quickly enough, corals can recover.

Have mesophotic corals’ diversity and resilience been studied in other tropical regions and if so how similar is it to the results you’ve had in the Chagos?

There are now quite a few people studying mesophotic reefs around the world, such as in the Caribbean and in the Pacific Ocean, but just not at the same scale as shallow reefs. There are a lot of similarities between the Pacific mesophotic reefs and the Indian Ocean ones, but the coral reefs in the Caribbean are quite different, i.e. with different species.

What is the one thing that we could all do, as individuals, to reduce the stress on mesophotic reefs?

One way you can help is, if eat fish, to look at how it has been fished. So, for instance, trawling destroys the habitat far more as compared to hook and line fishing. Also being aware and spreading awareness. This is an environment that is fragile, and which is very important to us and the Earth.

Literature References

- Diaz et al. (2025) Predicting the distribution of mesophotic coral ecosystems in the Chagos Archipelago: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ece3.71130

- Diaz et al. (2024) Diverse and ecologically unique mesophotic coral ecosystems in the central Indian Ocean: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00338-024-02535-3.pdf

- Radice et al. (2024) Recent trends and biases in mesophotic ecosystem research: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsbl.2024.0465

- Diaz (2023) Investigating the diversity and distribution of Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems in the Chagos Archipelago: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/bms-theses/446/

- Diaz et al. (2023) Mesophotic coral bleaching associated with changes in thermocline depth: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-42279-2.pdf

- Diaz et al. (2023) Light and temperature drive the distribution of mesophotic benthic communities in the Central Indian Ocean: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/ddi.13777

- Rocha et al. (2018) Mesophotic coral ecosystems are threatened and ecologically distinct from shallow water reefs https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaq1614

Further Info

- Introduction to Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/mesophotic.html

- Mesophotic Reefs in the Indian Ocean Region project page: https://www.marine.science/project/mesophotic-reefs-in-the-british-indian-ocean-territory/#

marineLIVE

marineLIVE webinars feature guest marine biologists talking about their research into the various organisms that inhabit our seas and oceans, and the threats that they face. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for marine life is all that’s required!

- Upcoming marineLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/cc/marinelive-webinars-3182319

- Donate to marineLIVE: https://gofund.me/fe084e0f

- marineLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/marinelive-blog/

- marineLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE-t2dzcoX59iR41WnEf21fg&feature=shared

marineLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company with funding from the British Ecological Society.

- Explore upcoming events and training opportunities from the Biological Recording Company: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/o/the-biological-recording-company-35982868173

- Check out the British Ecological Society website for more information on membership, events, publications and special interest groups: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/