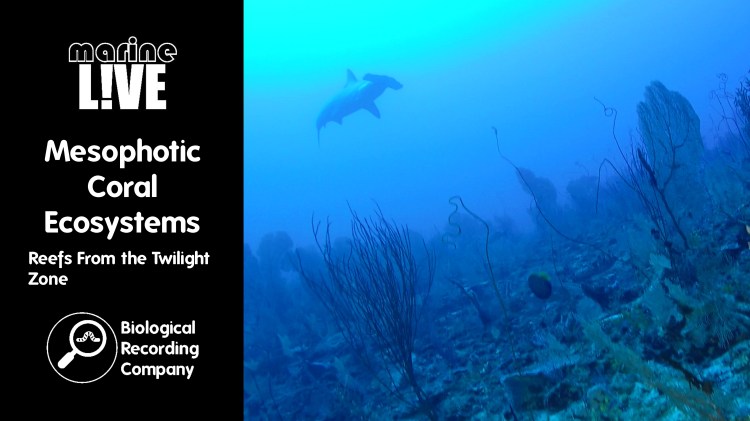

Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems: Reefs From the Twilight Zone

Mesophotic coral ecosystems, found roughly between 30m and 150m deep in tropical and subtropical areas, still remain poorly known. They’ve nonetheless been seen to be diverse and unique, harbouring numerous species; but are already threatened by climate change. This presentation will dive into the mysteries these ecosystems hold, including the tools being used to study them in the Chagos Archipelago, Indian Ocean.

This work was undertaken by Dr Clara Diaz with Dr Nicola Foster, Dr Phil Hosegood, Prof Kerry Howell, Dr Edward Robinson, Mr Peter Ganderton and Mr Adam Bolton from the University of Plymouth

Q&A with Dr Clara Diaz

Dr Clara Diaz is a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Plymouth investigating the ecology and resilience of mesophotic coral ecosystems

How can a reef be measured in dollars?

An ecosystem’s worth is measured by attributing economic services. For instance, coral reefs are very good at sheltering islands and coasts against waves and so it’s like an insurance that protects coasts from damage. Reefs also draw a lot of tourists, with diving activities especially. Another example is the profit from the fisheries, as the reef provides habitat and food for these commercially important fishes. An estimation of all these profits and costs are made to calculate the ecosystem service an ecosystem provides to humans.

Why do you think the corals recovered after the bleaching event?

This mass bleaching event we saw was due to the extreme deepening of the thermocline – the separation between cold and warm waters from a seasonal current. So the warm water, which is on top and in shallower waters, went very deep and stressed the coral (it was 29 degrees celsius at 100m deep!), causing this bleaching event, where the zooxanthellae (algae) were expelled from the corals. Fortunately, this warming event did not last for critically long, with the conditions coming back to normal afterwards, so the algae that had been released during the bleaching event came back to the coral. Some of the coral died unfortunately, but many survived. We were really pleased to see some of the coral recover and that they could recover after a bleaching event – if the conditions come back to normal quickly enough, corals can recover.

Have mesophotic corals’ diversity and resilience been studied in other tropical regions and if so how similar is it to the results you’ve had in the Chagos?

There are now quite a few people studying mesophotic reefs around the world, such as in the Caribbean and in the Pacific Ocean, but just not at the same scale as shallow reefs. There are a lot of similarities between the Pacific mesophotic reefs and the Indian Ocean ones, but the coral reefs in the Caribbean are quite different, i.e. with different species.

What is the one thing that we could all do, as individuals, to reduce the stress on mesophotic reefs?

One way you can help is, if eat fish, to look at how it has been fished. So, for instance, trawling destroys the habitat far more as compared to hook and line fishing. Also being aware and spreading awareness. This is an environment that is fragile, and which is very important to us and the Earth.

Literature References

- Diaz et al. (2025) Predicting the distribution of mesophotic coral ecosystems in the Chagos Archipelago: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ece3.71130

- Diaz et al. (2024) Diverse and ecologically unique mesophotic coral ecosystems in the central Indian Ocean: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s00338-024-02535-3.pdf

- Radice et al. (2024) Recent trends and biases in mesophotic ecosystem research: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsbl.2024.0465

- Diaz (2023) Investigating the diversity and distribution of Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems in the Chagos Archipelago: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/bms-theses/446/

- Diaz et al. (2023) Mesophotic coral bleaching associated with changes in thermocline depth: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-42279-2.pdf

- Diaz et al. (2023) Light and temperature drive the distribution of mesophotic benthic communities in the Central Indian Ocean: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/ddi.13777

- Rocha et al. (2018) Mesophotic coral ecosystems are threatened and ecologically distinct from shallow water reefs https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaq1614

Further Info

- Introduction to Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/mesophotic.html

- Mesophotic Reefs in the Indian Ocean Region project page: https://www.marine.science/project/mesophotic-reefs-in-the-british-indian-ocean-territory/#

marineLIVE

marineLIVE webinars feature guest marine biologists talking about their research into the various organisms that inhabit our seas and oceans, and the threats that they face. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for marine life is all that’s required!

- Upcoming marineLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/cc/marinelive-webinars-3182319

- Donate to marineLIVE: https://gofund.me/fe084e0f

- marineLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/marinelive-blog/

- marineLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE-t2dzcoX59iR41WnEf21fg&feature=shared

marineLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company with funding from the British Ecological Society.

- Explore upcoming events and training opportunities from the Biological Recording Company: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/o/the-biological-recording-company-35982868173

- Check out the British Ecological Society website for more information on membership, events, publications and special interest groups: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/

More on marine biology

British Springtails: How Many Species Really Are There?

Springtails – small invertebrates closely related to insects – are everywhere: in the soil, up trees, in rockpools, and even being blown around thousands of feet up in the air. They can reach densities of thousands per cubic metre of substrate, yet we know disproportionately little about them. We have a poor grasp on even the most basic level of information: which, and how many, species we have in the UK. James will put forward the case that we may be underestimating the diversity of springtails we have in the UK, and explain how we can resolve this using various sources of data, from citizen science to whole genome sequences. He will also delve into how getting a firm grasp of springtail diversity, as well as understanding how this diversity has come to be, has implications for evolutionary biology, ecology, invasion biology, and conservation.

Q&A with James McCulloch

James McCulloch is the National Recorder for springtails (Collembola), and a PhD student in the evolutionary genomics of springtails at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Cambridge.

What do you see as the main barriers in terms of recruiting people into recording springtails?

I think that the FSC springtail AIDGAP key published in 2007 was really useful for people with microscopes to identify springtails. However, beginners who purchase this key as a starting point to identify springtails could find it quite difficult because a lot of their features do rely on microscopy. But a lot of springtails can be identified from record photos. Creating a resource that is focused more on identification through photos as opposed to microscopy would be a good way to encourage new recorders.

What is the practical impact of these cryptic species on springtail recording?

When we realised how much cryptic diversity there might be in springtails, we wondered how we were going to keep track of them. A lot of people don’t have access to genetic sequencing facilities, and it could make getting into springtail recording very difficult or off-putting for new people. I think that it is still useful to record springtails that are different morphologically as morphospecies. That way we can still get a lot of data while acknowledging that they may not be species in the strict genetic sense; these data will still be useful given that cryptic species are likely to be similar ecologically.

Do you need fresh specimens for genome sequencing?

Ideally the specimens should be alive until they go into the lab. They are then flash frozen at -70 degrees. This prevents the DNA from breaking down into smaller chunks and we can get longer reads that are much easier to piece together into a genome. Short-read genome sequences can be used for population genomic analysis, which can tell us about population movements and gene flow, for example, and these can be assembled from dead specimens stored in high concentration ethanol for a short time. These are most useful when there is already a high-quality long-read reference genome for that species or a closely-related species, though the pace of methodological advancements will make it easier to assemble good reference genomes from dead specimens in the near future.

Has there been any progress in using eDNA in the study of springtails?

I am not aware of any eDNA work on springtails specifically. Since springtails occur at such high densities in soil, it isn’t totally unreasonable to consider studying them from an eDNA perspective. However, we don’t have a comprehensive DNA database for springtails yet so we wouldn’t be able to confidently identify a lot of the genetic sequences that we would see in the eDNA samples.

Literature References

- McCullock (2025) Entomobrya petri sp. nov.: A new species of springtail found in the British Isles: https://doi.org/10.25674/476

- Hutchinson and McCulloch (2024) Fasciosminthurus quinquefasciatus (Symphypleona: Bourletiellidae), New to Britain: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379733637_Fasciosminthurus_quinquefasciatus_Symphypleona_Bourletiellidae_New_to_Britain

- Du et al. (2024) Revisiting the four Hexapoda classes: Protura as the sister group to all other hexapods: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2408775121

- Chen et al. (2019) Structure and functions of the ventral tube of the clover springtail Sminthurus viridis (Collembola: Sminthuridae): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330711582_Structure_and_functions_of_the_ventral_tube_of_the_clover_springtail_Sminthurus_viridis_Collembola_Sminthuridae

- Yu et al. (2014) Whole-genome-based phylogenetic analyses provide new insights into the evolution of springtails (Hexapoda: Collembola): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1055790324001611

- Whalley and Jarzembowski (1981) A new assessment of Rhyniella, the earliest known insect, from the Devonian of Rhynie, Scotland: https://www.nature.com/articles/291317a0

- Potapov et al. (2023) Globally invariant metabolism but density-diversity mismatch in springtails: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-36216-6

- Hensel et al. (2013) Tunable nano-replication to explore the omniphobic characteristics of springtail skin: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/245540698_Tunable_nano-replication_to_explore_the_omniphobic_characteristics_of_springtail_skin

- Lukić et al. (2018) Setting a morphological framework for the genus Verhoeffiella (Collembola, Entomobryidae) for describing new troglomorphic species from the Dinaric karst (Western Balkans): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328285277_Setting_a_morphological_framework_for_the_genus_Verhoeffiella_Collembola_Entomobryidae_for_describing_new_troglomorphic_species_from_the_Dinaric_karst_Western_Balkans

- Lukić et al. (2019) Distribution pattern and radiation of the European subterranean genus Verhoeffiella (Collembola, Entomobryidae): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/zsc.12392

- Dukes et al. (2022) Specific and intraspecific diversity of Symphypleona and Neelipleona (Hexapoda: Collembola) in southern High Appalachia (USA): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364257425_Specific_and_Intraspecific_Diversity_of_Symphypleona_and_Neelipleona_Hexapoda_Collembola_in_Southern_High_Appalachia_USA

- Zhang et al. (2025) Diversification of alpine soil animals corroborates uplifts and environmental changes of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and Himalayas: Insights from molecular phylogeny and cryptic diversity of the Isotoma quadridentata Complex (Collembola: Isotomidae): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/zsc.70004?af=R

- Martin et al. (2019) Recombination rate variation shapes barriers to introgression across butterfly genomes: https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.2006288

- Chernova et al. (2009) Ecological significance of parthenogenesis in Collembola: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S0013873810010033

- Riparbelli et al. (2006): Centrosome inheritance in the parthenogenetic egg of the collembolan Folsomia candida: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16906420/

- Hart et al. (2025) Genomic divergence across the tree of life: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2319389122

Further Info

- Checklist of the Collembola of the world: https://www.collembola.org/

- A Key to the Collembola (Springtails) of Britain and Ireland: https://www.field-studies-council.org/shop/publications/springtails-aidgap/)

- AJC Springtails: https://collembolla.blogspot.com/

- Ed Phillips’ springtail photographs: www.edphillipswildlife.com/collembola-springtails

- Frank Ashwood Springtail photographs: https://www.frankashwood.com/macrophotography/collembola

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

AI-powered Bioacoustics with BirdNET

How can computers learn to recognise birds from sounds? The Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Chemnitz University of Technology are trying to find an answer to this question.

Their research has led to the development and evolution of BirdNET – an artificial neural network that has learned to detect and classify avian sounds through machine learning.

This webinar provides an introduction to BirdNET, how it works and and how the use of BirdNET can be scaled to generate huge biodiversity datasets (with a case study from Wilder Sensing).

BirdNET: Advancing Conservation with AI-Powered Sound ID

Dr Stefan Kahl (Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Chemnitz University)

Learn about how BirdNET was built with Dr Stefan Kahl. He’ll cover some basics about AI for sound ID, present a few case studies that have used BirdNET at scale and then conclude with some thoughts on the future of AI in bioacoustics.

Dr Stefan Kahl is a computer science post-doc at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Chemnitz University in Germany, working on AI algorithms for animal sound ID. He is lead of the BirdNET team, where they develop state-of-the-art tools for anyone interested in large-scale acoustic monitoring.

How did you handle species with multiple distinct call types?

We put all of the files from one species into a folder and told the AI model that this is one species. That has worked relatively well, these models are able to distinguish different call types for the same species so we can do calls, we can do songs, we can do all kinds of call types. We know that these feature vectors embed these call types, and we can re-construct it. So, after you’ve run BirdNET, instead of the class scores if you take these embeddings, you can do a clustering and cluster out these different call types and you’ll end up with a nice visualisation.

Sometimes what people will do, if they are interested in something specific like mating calls, you can train a custom classifier, as long as it is a category. So, if you can categorise it, it can become a model. So, if you want to run a call type model instead of a species model you can. One category of call types which is challenging is flight calls. Not all of the species have sufficient flight call data and flight calls tend to be short. I would exclude those.

How did you settle on the three second segments for the sampling?

We wanted to reduce the input size as these models are computationally expensive. So, the bigger the input, the more computationally expensive, so we want the smallest spectrogram you can have that still retains all the detail.

During my PhD, I did an empirical study looking at the average bird song length and the literature gave a time of two seconds. I added half a second before and after to have some wiggle room and that’s why we chose three seconds. We know some people are using five seconds and that is usually fine if you have longer context windows that might help with call sequences. Sometimes three seconds is not good enough as you need a temporal component to it.

Do recordings need to be added to Xeno-canto or can you access recordings from Merlin and other systems?

Merlin doesn’t currently leverage user’s observations, i.e., Merlin is not collecting data that we can use. We have access to recording submitted to eBird and Macaulay Library, though Xeno-Canto is a bit faster to allow non-bird uploads. The best The best way for users of BirdNET-Pi is BirdWeather (get a device ID and hook it up to the BirdWeather platform).

Is there a way to reduce the number of false positives in BirdNET?

Yes, you can also use false positives to train a custom classifier and then BirdNET will (hopefully) learn to separate target from non-target sounds. So basically, using those “negative” samples to train a model.

What is needed to scale BirdNET fast?

More data. Plus anecdotal evidence on how people are using it, so we can learn what we need to tackle to make it more useful.

Do you know if anyone is using BirdNET to look at the relationship between anthropogenic noise and species abundance?

Not abundance but disturbance – there’s a project going on in Yellowstone National Park looking at the impact of snowmobiles on bird vocalisation. They found that engine sounds are a significant disturbance and needs to be managed, i.e., birds will stop vocalizing for extended periods of time, even well after the snowmobiles have passed.

What data augmentation techniques do you use (if any) to expand your training dataset?

MixUp (mixing multi recordings into one) is the most important and most effective augmentation. We had a student look into augmentations a while ago.

A Scalable Platform for Ecological Monitoring

Lorenzo Trojan (Wilder Sensing)

How can we measure the impact of wildlife restoration, assess biodiversity loss, and evaluate the effectiveness of environmental policies? Passive bioacoustic monitoring offers a powerful solution, enabling continuous, large-scale coverage of ecosystems. To fully harness its potential, we need a scalable, robust software platform capable of handling vast audio datasets, detecting key biological sounds using AI, and extracting ecological insights such as species richness and assemblage trends.

This presentation explores the challenges of biodiversity monitoring with passive audio recorders, the processing and analysis of large-scale acoustic data, and the technologies that make this approach viable and impactful. We’ll also showcase how the Wilder Sensing Platform is purpose-built to meet these demands—providing researchers, conservationists, and policymakers with an intuitive, scalable, and efficient tool for biodiversity monitoring and ecological surveys.

Dr Lorenzo Trojan is a technologist with a PhD in Astrophysics and over a decade of leadership experience in high-growth tech startups. His expertise spans remote sensing, cloud computing, DevOps, and AI. As CTO of Wilder Sensing, he leads the development of a scalable platform for ecological monitoring, driven by a commitment to innovation, inclusivity, and impact.

Useful links

- BirdNET website: https://birdnet.cornell.edu/

- BirdNET GitHub repository: https://github.com/birdnet-team

- BirdNET Analyzer documentation: http://birdnet.cornell.edu/analyzer

- Identifying Bird Sounds with the BirdNET Mobile App: https://www.youtube.com/embed/f144CSEoYuk

- What’s that bird song? ID birds by sound with BirdNET: https://www.youtube.com/embed/MQHunTLt1TI

- Kahl et al. (2021) BirdNET: A deep learning solution for avian diversity monitoring: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1574954121000273

- Pérez-Granados (2023) BirdNET: applications, performance, pitfalls and future opportunities: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ibi.13193

- Wilder Sensing website: https://wildersensing.com/

- Sign up for the Wilder Sensing e-newsletter: https://2e428x.share-eu1.hsforms.com/2XxP8d_6lRSmBIKH7uwruXQ

- Contact Wilder Sensing: https://wildersensing.com/contact/

Wilder Sensing ecoTECH blogs

- How Can We Use Sound to Measure Biodiversity: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2024/07/09/bioacoustics-1/

- Can Passive Acoustic Monitoring of Birds Replace Site Surveys blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2024/09/17/bioacoustics-2/

- The Wilder Sensing Guide to Mastering Bioacoustic Bird Surveys: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2024/11/26/bioacoustics-3/

- Bioacoustics for Regenerative Agriculture: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2025/03/31/bioacoustics-for-regen-ag/

- AI-powered Bioacoustics with BirdNET: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2025/07/08/birdnet/

Event partners

This blog was produced by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with Wilder Sensing, Wildlife Acoustics and NHBS.

- Sign up for the Wilder Sensing e-newsletter: https://2e428x.share-eu1.hsforms.com/2XxP8d_6lRSmBIKH7uwruXQ

- Watch the Wildlife Acoustics video: https://youtu.be/kjtluiV3DiM

- The Song Meter Micro 2 is now available for only £155.99 from NHBS (previously £245): www.nhbs.com/song-meter-micro-2

- BirdMic Parabolic Microphone with Audio Interface: www.nhbs.com/birdmic

- Check out the NHBS Field Guide Sale: www.nhbs.com/spring-promotions

More for environmental professionals

Protected: Flower-Insect Timed (FIT) Counts

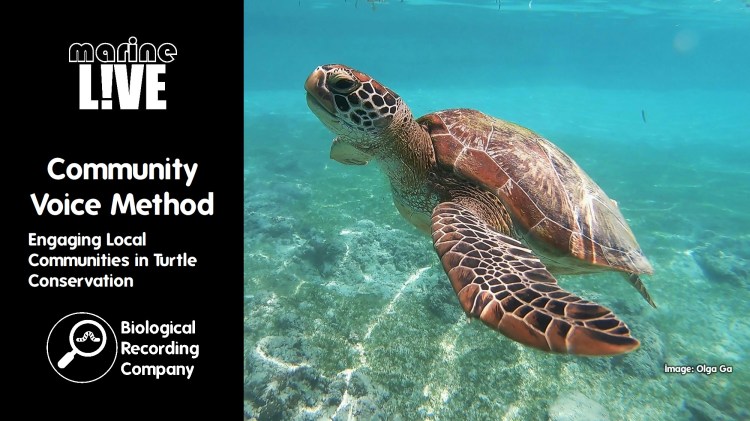

Community Voice Method: Engaging Local Communities in Turtle Conservation

Hear about how the documentary film-based Community Voice Method (CVM) has been used to engage Caribbean Island communities in developing marine turtle conservation policy. The methodology will be discussed along with experiences of its applications in various communities across the Caribbean UK Overseas Territories. We’ll explore the challenges and opportunities of using this method, and provide case studies on the application of CVM in supporting population recovery.

Q&A with Amdeep Sanghera

Amdeep Sanghera is the UK Overseas Territories Conservation Manager at the Marine Conservation Society. He is a trained social scientist with experience in marine turtle conservation, tropical fisheries research and community-based conservation. Amdeep initially joined MCS in 2008 as the Turks and Caicos Islands Turtle Project Officer, and was based out in the Caribbean, helping to deliver conservation measures for the island’s marine turtle populations. As part of a team, Amdeep enabled the island’s fishing communities to shape these laws through the Community Voice Method (CVM) documentary film tool. Building on this, Amdeep is now focusing on the Caribbean UK Overseas Territories, employing the CVM as part of partnership projects to work with communities to improve the management of turtle populations.

How were the participants chosen for the consultations and workshops?

Because we wanted to develop resilient solutions that reflected community values, the workshops were open to everyone. This wasn’t just about just turtle conservation and so we wanted to nestle this within the wider issues that were happening on these islands. By having wider participation, we could get solutions that would be more widely accepted. We did, however, target some groups, like the fishing community and local conservationists, to make sure that their voices were heard.

Why was the Community Voice Method used?

We’d heard about this method through academic research and that it had some very good results. We spoke to the stakeholders about it and they were very keen to try it. It worked really well because not only did the fishermen that I spoke to feel that they had a voice, it also helped to bring a lot of trust. Now that the territory partners are seeing the results, they want training in this method.

Has the Community Voice Method had a direct impact on protecting turtles and turtle conservation?

Community Voice Method is a long-term process for developing trust with communities and looking to work with them to create conservation solutions. Community Voice Method has given the communities a voice, a platform, and really does empower them. We’ve been going back to the Turks and Caicos to speak to the fishermen and they’ve been telling us that they’re no longer catching the large turtles, that they understand that they are the breeders and should be protected. We can triangulate that with community perceptions and the fact that compliance has really risen. And we are now seeing turtle nesting happen in places where the project has never detected it before. We think the nesting turtle population could be in the early stages of recovery, and I think this is due to fishers and enforcement officers working with the new laws. I think CVM has had a significant role in bringing about this shift, and resulting turtle conservation.

Literature References

- Cumming et al. (2021) Putting stakeholder engagement in its place: How situating public participation in community improves natural resource management outcomes: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10708-020-10367-1

Further Info

- Marine Conservation Society: https://www.mcsuk.org/

- Community Voice Method: http://communityvoicemethod.org/

- Community Voice Method Explained video: https://vimeo.com/150885111

- Turtles in Montserrat – Listening to Local Voices video: https://vimeo.com/778198665

- MCS Community Voice Method videos: https://www.mcsuk.org/ocean-emergency/people-and-the-sea/community-voice-method/

marineLIVE

marineLIVE webinars feature guest marine biologists talking about their research into the various organisms that inhabit our seas and oceans, and the threats that they face. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for marine life is all that’s required!

- Upcoming marineLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/cc/marinelive-webinars-3182319

- Donate to marineLIVE: https://gofund.me/fe084e0f

- marineLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/marinelive-blog/

- marineLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE-t2dzcoX59iR41WnEf21fg&feature=shared

marineLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company with funding from the British Ecological Society.

- Explore upcoming events and training opportunities from the Biological Recording Company: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/o/the-biological-recording-company-35982868173

- Check out the British Ecological Society website for more information on membership, events, publications and special interest groups: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/

More on marine biology

Protected: Social Wasps of the UK

Recording Beetles at Tolworth Court Farm

Blog post by Joss Carr

This article recounts the Beetle Field Recorder Day held at Tolworth Court Farm on Friday 25th April in collaboration with Citizen Zoo and London Natural History Society.

It was a gloriously sunny Friday morning when twenty-four intrepid naturalists ventured to Tolworth Court Farm in South-west London in search of beetles. We were a mixed group, including representatives from three organisations: the Biological Recording Company, Citizen Zoo and Rewilding Britain (the latter of which had sent along two photographers to capture the day). Our leader for this Field Recorder Day was beetle specialist Connor Butler.

Between the participants, a wide range of expertise was represented, with some individuals having never taken a concerted look at beetles before and others having spent years studying them.

Wild Tolworth

The site of choice – Tolworth Court Farm – is a 43-ha Local Nature Reserve (LNR) in the borough of Kingston. Managed by Citizen Zoo as a rewilding site through the ‘Wild Tolworth’ project, Tolworth Court Farm features an exciting range of habitats from open meadows with long grass, to woodland, to the chalk stream of the Hogsmill River, and a small patch of boggy marsh. It has been called one of London’s leading nature reserves, and rewilding efforts are set to include the introduction of a herd of Sussex cattle to reinstate a semi-natural grazing regime for the benefit of the site’s plant life and invertebrates and the expansion of the boggy area into a larger area of wetland.

Citizen Zoo are also incredibly keen to engage biological recorders and the local community with volunteering on the site. Such community engagement has the dual benefits of not only helping understand and better inform conservation management but also helps remedy some of the anti-social behaviour (such as fly-tipping) that the site was previously known for. Research suggests individuals responsible for such behaviour are less likely to commit such acts if there is a regularly present volunteer body on site.

The aims of the day were to:

- engage volunteers with the Wild Tolworth rewilding project and the Tolworth Court Farm Fields site.

- educate volunteers and inspire their interest in beetles.

- generate biological records which contribute to building understanding of the site to inform conservation management.

In regards specifically to biological recording, all volunteers were encouraged to record their findings, either on paper sheets which they could be later digitised through uploading to iRecord via the London Natural History Society activity, or via direct upload to the iRecord app.

Grassland Beetles

After a successful rendezvous and brief introduction to the site (from Citizen Zoo) and to the basics of beetles (from Connor), the group ventured into the main site ‘Tolworth Court Farm Fields’ where volunteers immediately got to work amongst the long grass and in the hedgerows. Armed with sweep nets, pooters and collection pots, a wide range of species – including a range of beetles – were quickly revealed. The overhead sun, mild temperature and low wind made for a perfect day for observing insects.

Some of the species collected from the long grass included 24- and 14-spot ladybirds (Subcoccinella vigintiquattuorpunctata and Propylea quattuordecimpunctata) as well as a nice range of Apionid weevils such as Oxystoma craccae and Oxystoma pomonae (from Common Vetch Vicia sativa) and Protapion fulvipes.

The much larger broad-nosed weevil Liophloeus tessulatus was also a delight to see. Connor was able to provide useful tips and tricks for the identification of different families and more generally help newcomers learn about some of the beetles they had collected.

The group opted for an early lunch beneath the shade of a large English Oak (Quercus robur) at the margin of the Seven Acres field. In the time-honoured fashion of naturalists – who cannot take a break much longer than 10 minutes before getting back to looking at wildlife – some volunteers soon turned to the hedges behind the lunch spot where several insects were active. The Mirid plant bug Dryophilocoris flavoquadrimaculatus was common here, having likely descended from the oak above which is its host plant.

Woodland Beetles

After finishing our lunch the party then moved on to a small area of woodland further into the site. Connor was keen to explore the deadwood habitats present, and indeed several deadwood specialist beetles were found, including the black ground beetles Nebria brevicollis and Abax parallelelepipedus, both common in this habitat.

Whilst others occupied themselves in the woodland, some volunteers turned to a small but promising-looking grassy patch on the woodland margin. Excitingly this turned up the tortoise beetle Cassida vibex, which gave Elliot Newton (Citizen Zoo) the chance to delight everyone with his ‘favourite fact’ about the fecal shield produced by tortoise beetle larvae which they used to defend themselves. This grassy patch also yielded the uncommonly recorded vetch-feeding bean weevil Bruchus atomarius as well as its more common sister species Bruchus loti.

Marsh Beetles

The group then moved onwards down to the small marsh area that will be expanded into a bigger wetland through the Wild Tolworth project.

The underside of an old artificial refugium for reptile surveys revealed several individuals of the click beetle Agriotes lineatus as well as several Turtle-bugs Podops inuncta. Mick Massie took some excellent photos of these species shown below.

Sweep-netting of the grasses and sedges in this area also revealed some interesting marsh specialist beetles including numerous Microcara testacea (a species of marsh beetle), Coccidula rufa (the Red Marsh Ladybird) and Bembidion biguttatum (a small ground beetle which favours muddy ground near water). A definite highlight was Elaphrus riparius, a species only found at the margins of freshwater (Hackston, 2024).

Riverbank Beetles

The final site of the day was down on the banks of the Hogsmill River, a lovely chalk stream that was breathtakingly clear and alive with riverflies on our visit. The river banks were cloaked in Pendulous Sedge Carex pendula and Cow Parsley Anthriscus sylvestris, the latter yielding one of the days most exciting finds of the day in the form of the longhorn beetle Phytoecia cylindrica, which feeds on Anthriscus sylvestris and other umbellifers. Numerous other insects including damselflies and hoverflies were also recorded here. Right before departing we were bid farewell by the final beetle of the day, an Orange Ladybird Halyzia sedecimguttata sitting calmly on a leaf overhanging the bridge that leads out of the site.

The Results & Next Steps

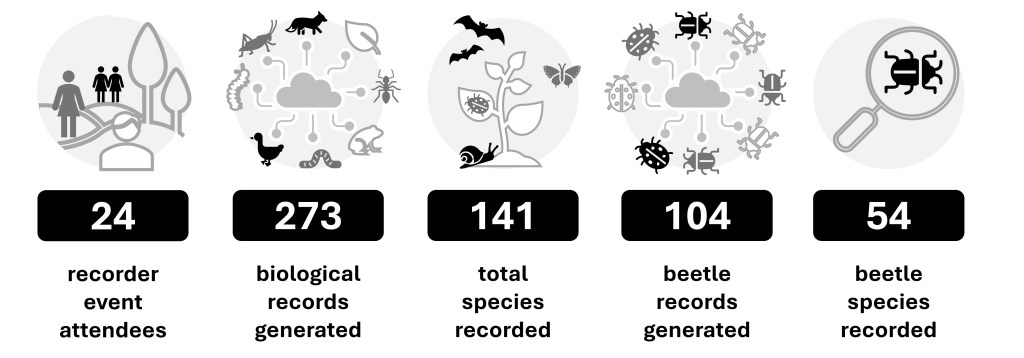

All in all it was a very productive day with 24 volunteers engaged and 273 biological records generated of 141 species in total, including 104 records of 54 species of beetle.

Several species found represent new records for the site which will continue to contribute towards building a picture of the biodiversity present in order to inform future conservation.

Thank you very much to all who attended and and contributed valuable data to the project. As always, our data is gathered through iRecord so that it is automatically accessible to Greenspace Information for Greater London (GiGL) and the relevant National Recording Schemes & Societies.

What’s next? We’ll be returning to Tolworth Court Farm in July for a Fly Field Recorder Day with Martin Harvey and in October for a Fungi Field Recorder Day with Dr Mark Spencer, plus we have other days planned at more sites across London. You could also sign up to our Longhorn Beetles of the UK online course to expand your beetle knowledge!

Learn more about British wildlife

Insects That Live In The Sea: Why Are There Are So Few?

Insects are everywhere – but only on land and in freshwater. Around a million species of insect have been described, but less than 2000 live in close association with the sea, with only a handful of chironomid flies and hemipteran water skaters living fully marine lives. Even then, it can be argued that these fully ocean-going species live on top of the sea rather than in it. Why have insects been so unsuccessful at colonising the oceans? In this presentation, we will look at those few insects that have managed to make some sort of accommodation with the sea, and speculate on why they are so few of them.

Q&A with Prof Stuart Reynolds

Stuart Reynolds is an Emeritus Professor of Biology at the University of Bath, and is an Honorary Fellow and Past President of the Royal Entomological Society. He is interested in everything about insects, from ecology to immunology, and behaviour to genomes. But he is especially fascinated by the astonishing evolutionary success of insects in colonizing almost every terrestrial and freshwater habitat.

Is there a name for the semi-circle shaped tree diagram?

It’s a phylogenetic tree, specifically an arc-style or semi-circular phylogenetic tree. These diagrams visually represent the evolutionary history and relationships between different species, organisms, or genes from a common ancestor.

Are there any marine insects in land-locked seas, such as the Salton Sea in California?

There are a lot of insects that are adapted to very salty conditions like you find in the California Sierra lakes and the Dead Sea. They do well in these hypersaline conditions because there aren’t that many fish. There are, of course, inland seas that are not hypersaline, but I don’t know if there are marine insects there. People haven’t studied them yet.

How is climate change likely to affect marine insects?

Sea levels will go up with climate change, but those insects, like the Halobates spp, that live out at sea should be fine. They’ll just float. The ones that live on the shoreline, they’ll simply migrate up the shoreline. So, I don’t think I’d expect big changes.

Do you think that the crustacea and insects have a common ancestor in the sea or from land?

The macroevolutionists are pretty clear that insects and crustaceans are indeed very closely related. The ancestral hexapod is thought to have arisen from a rather obscure class of crustacea called the Remipedia. These are crustacea that live in caves with brackish water. It looks, from DNA evidence, as though all hexapods are derived from this obscure order. The Remipedia live in salty water so the question really is if the ancestor of all hexapods today migrated into fresh water and then to land, or whether the colonisation of land by insects took place directly from brackish and salty water with freshwater habitats being colonised secondarily from the land, or whether the ancestral hexapods first entered fresh water and only later crawled up onto the land.

Accompanying Antenna Article

Join the Royal Entomological Society to receive the quarterly Antenna magazine: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/membership-and-community/membership/

Literature References

- Gosse (1855) A Manual of Marine Zoology of the British Isles Part I, p 178, London, J. van Voorst: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/22491#page/7/mode/1up

- Plateau, F. (1890) Journal de l’Anatomie 26, 236–269: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/178223#page/246/mode/1up

- Cheng (1976) Marine Insects: https://escholarship.org/content/qt1pm1485b/qt1pm1485b.pdf

- Tihelka et al. (2021) The evolution of insect biodiversity: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.057

- Pak et al. (2022) The evolution of marine dwelling in Diptera: https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7935

- Tang et al. (2022) Maritime midge radiations in the Pacific Ocean (Diptera: Chironomidae): https://doi.org/10.1111/syen.12565

- Page et al. (2004) Phylogeny of “Philoceanus complex” seabird lice (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00227-6

- Leonardi et al. (2022) How Did Seal Lice Turn into the Only Truly Marine Insects?: https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13010046

- Edwards (1926) On Marine Chironomidae (Diptera); with Descriptions of a New Genus and four New Species from Samoa: https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1926.tb07127.x

- Chang et al. (2021) Navigation in darkness: How the marine midge (Pontomyia oceana) locates hard substrates above the water level to lay eggs: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246060

- Templeton (1835) Description of a new hemipterous insect from the Atlantic Ocean (Halobates streatfieldiana): https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/48195#page/252/mode/1up

- White (1883) Report on the pelagic Hemiptera procured during the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger in the years 1873-1876. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/12810019#page/5/mode/1up

- Chang et al. (2024) Skimming the skaters: genome skimming improves phylogenetic resolution of Halobatinae (Hemiptera: Gerridae): https://doi.org/10.1093/isd/ixae015

- Mahadik et al. (2020) Superhydrophobicity and size reduction enabled Halobates (Insecta: Heteroptera, Gerridae) to colonize the open ocean: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64563-7

Further Info

- WoRMS (World Register of Marine Species): https://www.marinespecies.org/

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk