Climate change is widely recognised as being one of the major long-term threats to biodiversity. Freshwater ecosystems are particularly at risk from the impacts of climate change. This talk will explore the vulnerability of freshwater invertebrates to climate change, and what mitigation measures can be used to minimise the impacts on their populations.

As Conservation Director, Craig Macadam heads up the Conservation team at Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust. He leads Buglife’s freshwater work and is particularly interested in developing conservation action for less well-known species and overlooked freshwater habitats. For the past decade, Craig has been studying the Upland Summer Mayfly (Ameletus inopinatus) and the potential impacts of climate change on this montane species.

Q&A with Craig Macadam

How can one get involved with freshwater invertebrate monitoring?

Anyone can! There are plenty of opportunities for people at all levels. The Riverfly Monitoring Initiative is really easy to get involved with. Participants are taught how to identify 8 broad groups of riverflies and monitor a site on a monthly basis.

Will riverfly monitoring scores need to change in response to climate change?

Aquatic invertebrates are monitored to provide scores for different pressures on rivers, such as organic enrichment, sediment and flow. The impact of climate change on those populations may have an impact on what those scores say so this is something that we need to be mindful of in the future.

How much species-level monitoring of freshwater insects is undertaken?

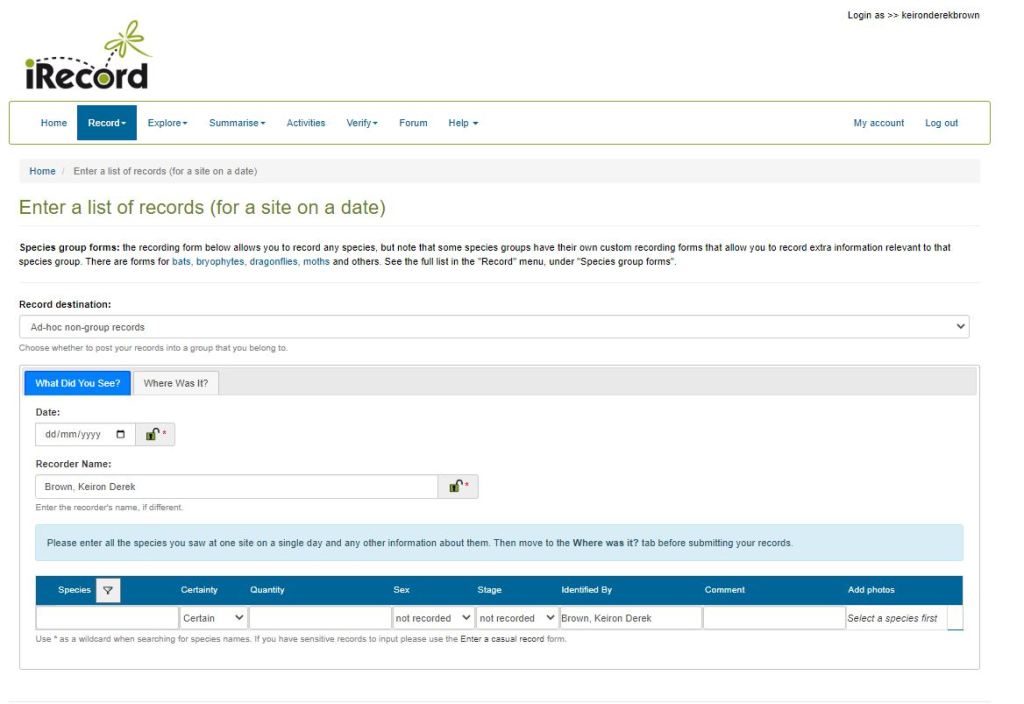

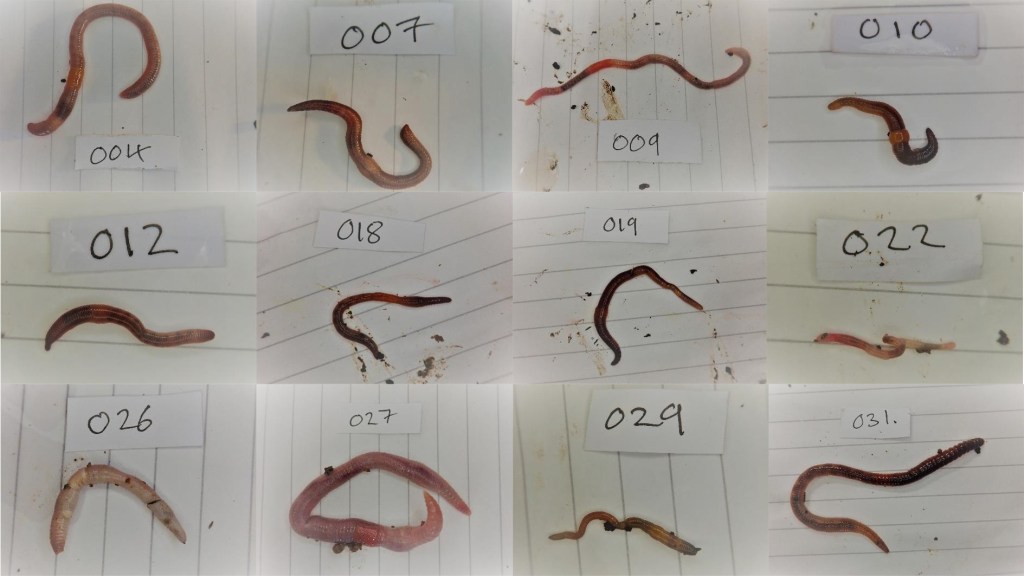

Riverfly monitoring through the Riverfly Monitoring Initiative usually goes to order or family level, rather than to species. The environment agencies of the UK do a lot of species-level monitoring and this provides the main source of data for freshwater insects to species level. However, there are also a number of opportunities for individuals to submit records. This includes some targeted surveys through specific RMI groups, and Buglife currently has a project asking people to check fenceposts along rivers for adult stoneflies. General records (of either adults or larvae) can be submitted to the Riverfly Recording Schemes via iRecord (preferably with a photo to help with verification).

What methods can be used to survey riverflies in order to establish if population changes have occurred?

There are different types of surveys that use different equipment. Generally, a standard pond net is used and it is a 3-minute sample that is used to compare sites or time periods (assuming the same method is used each time). Quantitative sampling can also be undertaken to establish the number of organisms per unit area by disturbing a set area of the bed of the river and this method is often used for population studies, though it doesn’t work so well in Scottish river systems because the substrate is too big.

What are degree days?

The standard temperature used in this study was 0°C. We were basically looking for the number of degrees above zero each day and adding them up. So if day 1 was 10°C and day 2 was 8°C, this would be recorded as 18 degree days.

Did you measure the change in diversity alongside the change in abundance?

This study focused on changes in abundance, rather than diversity. In the UK, we have lost 2 species of mayfly and 1 species of stonefly to extinction. Specialist species are often more at risk than generalist species.

Is there much hope for freshwater insects in areas where the chalk streams dry up for months on end?

Some chalk streams naturally dry up during summer and become wet again in the winter – these are known as winterbournes. This specific cycle can provide a home for specialist species, such as Scarce Purple Mayfly (Paraleptophlebia werneri) and the Winterbourne Stonefly (Nemoura lacustris), and England is a global hotspot for this type of habitat. The dry stage is just as important as the wet stages in these watercourses so it’s important that any habitat management considers both stages. You can read more about winterbourne species in The specialist insects that rely on the wet-dry habitats of temporary streams. Buglife does a lot of work on temporary water courses and does respond to threats to winterbourne specialists where we are aware of a threat. However, we are often not aware and encourage people to get in touch if they are concerned about a specific case.

Which varieties of trees should be planted alongside rivers?

Native trees such as alder rowan and willow are good species along rivers. You want trees where the leaf litter will break down quickly, so not trees with glossy leaves, such as beech.

Would adding more trees near the water increase water depletion from the river by the trees themselves?

Some trees take up more water than others. For example, willows take up a lot of water, and rowan and alder take less – you’ll often find alder along river channels. The shading that is provided by these trees is the key aspect, and water depletion from these trees should not be an issue considering these systems are generally quite damp with sufficient levels of rainfall – water is generally in good supply in these areas.

How can conservationists work with land managers to persuade allowing vegetation growth in impacted areas?

This is a big question. There are lots of different land managers, ranging from farmers to gamekeepers to ski slope managers! It’s important that we work with land managers and convince them to manage buffer strips along streams to protect the banks and provide shading, rather than managing the stream-side for the adjacent land use. This applies to lowland systems as well as upland systems.

Do UK/EU laws go far enough to help and support the conservation of aquatic invertebrates?

Trends illustrate the impact of EU laws as the abundance of invertebrates increases after the implementation of laws. For example, the introduction of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive was followed by a rise in the abundance of aquatic insects. EU laws have been good for the freshwater environment. However, we could go further and restore more of our rivers – they are currently very fragmented and natural flow processes need to be restored at a faster pace.

Literature references

- Macadam et al. (2022) The vulnerability of British aquatic insects to climate change

- Collen et al. (2012) Spineless : status and trends of the world’s invertebrates

- Hallman et al. (2017) More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas

- Hallman et al. (2019) Declining abundance of beetles, moths and caddisflies in the Netherlands

- Harvey et al. (2022) Scientists’ warning on climate change and insects

- IPBES (2019) Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

- Nash et al (2021) Warming of aquatic ecosystems disrupts aquatic-terrestrial linkages in the tropics

- Platts et al. (2019) Habitat availability explains variation in climate-driven range shifts across multiple taxonomic groups

- Shah et al. (2022) High elevation insect communities face shifting ecological and evolutionary landscapes

- Taubmann et al. (2011) Modelling range shifts and assessing genetic diversity distribution of the montane aquatic mayfly Ameletus inopinatus in Europe under climate change scenarios

- Wonglersak et al (2020) Temperature-body size responses in insects: a case study of British Odonata

Further info

- Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust

- Riverfly Recording Schemes

- The Riverfly Partnership

- Guardians of our Rivers

- freshwaterecology.info

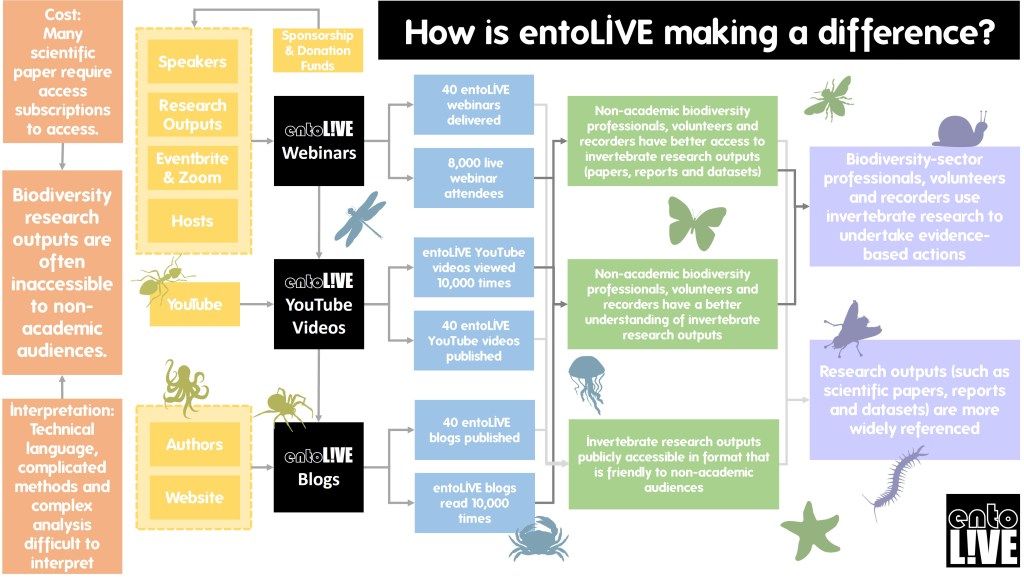

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2026

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is only possible due to contributions from our partners and supporters.

- Find out about more about the British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk/

- Check out the Royal Entomological Society‘s NEW £15 Associate Membership: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/shop/membership-and-fellowship/associate-member/

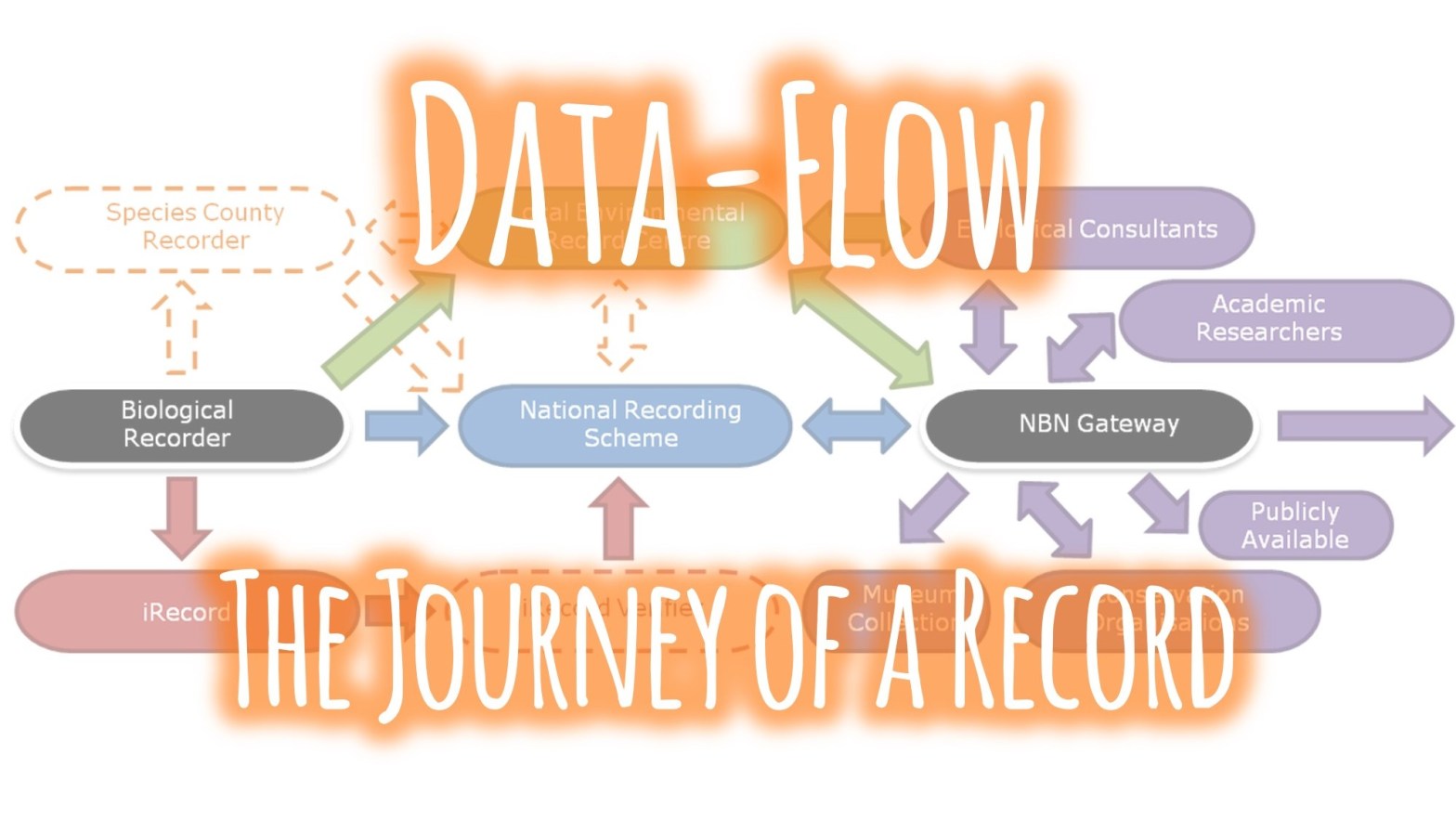

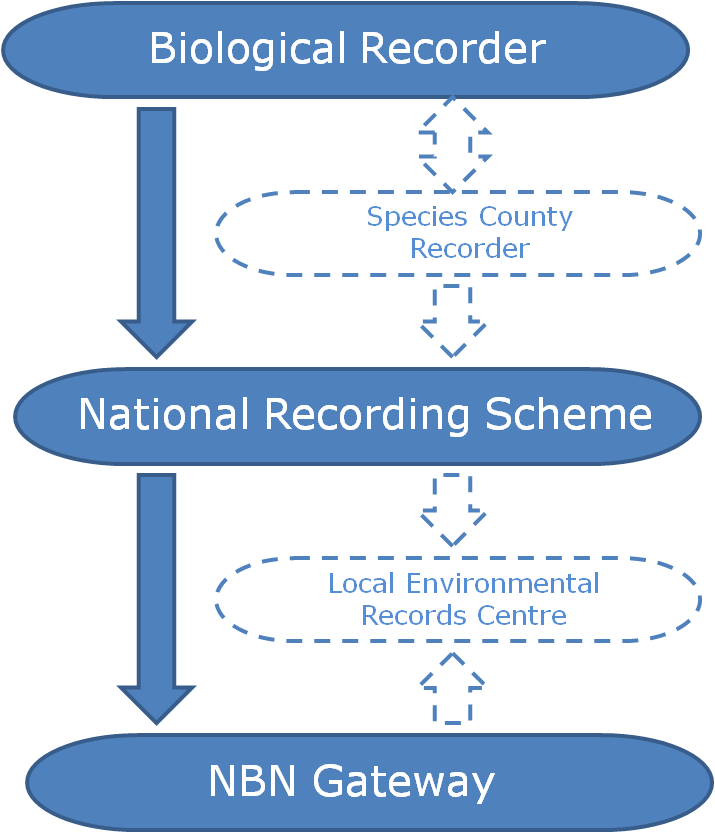

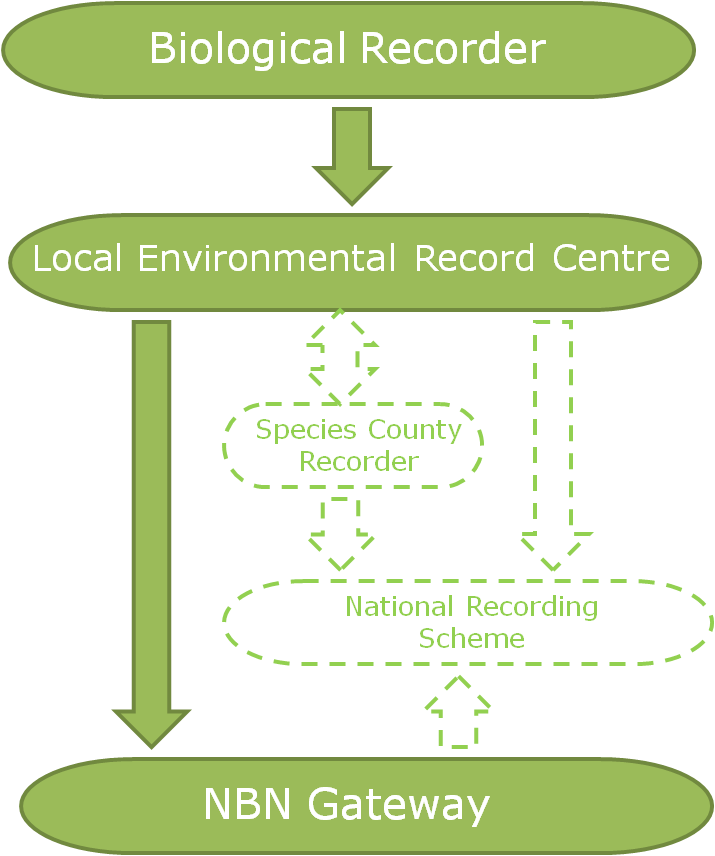

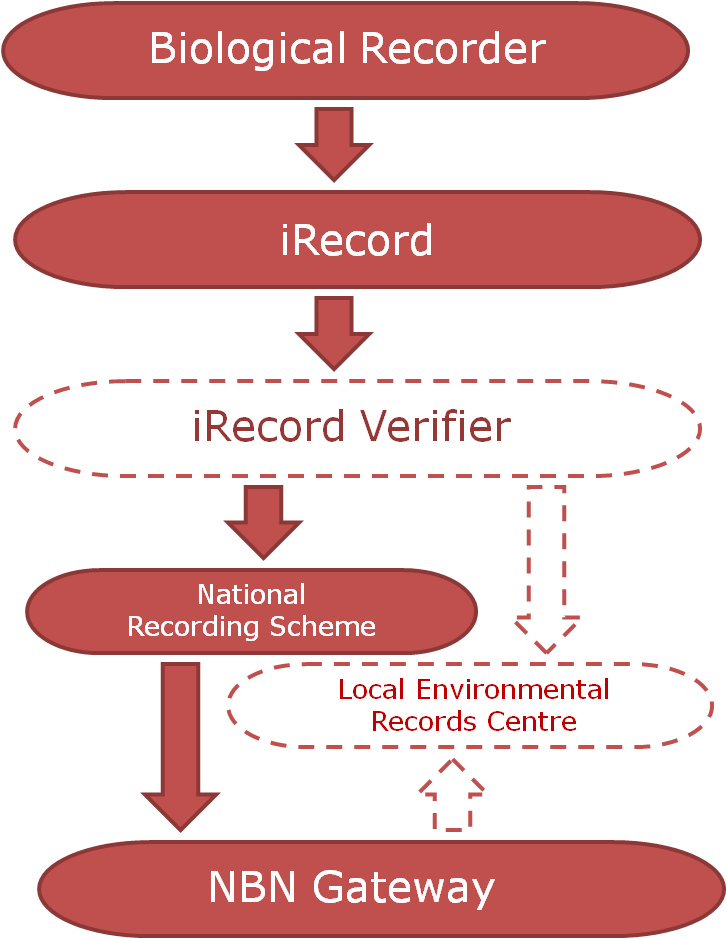

f you would like the record to be considered when decisions are made regarding the area the record was made in, you should submit your record to the

f you would like the record to be considered when decisions are made regarding the area the record was made in, you should submit your record to the  The two routes above consider the use of the record and there are valid arguments for both routes. So why not send all of your records to both the relevant NRS and the LERC? Well, ideally that’s the best option but it’s not always pragmatic for a biological recorder to be able to do this due to the amount of administration that would entail. In fact, even just sending your records to several different LERCs or NRSs can be an administration mountain!

The two routes above consider the use of the record and there are valid arguments for both routes. So why not send all of your records to both the relevant NRS and the LERC? Well, ideally that’s the best option but it’s not always pragmatic for a biological recorder to be able to do this due to the amount of administration that would entail. In fact, even just sending your records to several different LERCs or NRSs can be an administration mountain!