The FSC BioLinks Project was a £1.6 million biological recording and ID training project run by the Field Studies Council with a large number of project partners and funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. This blog is the first in a series by Keiron Brown (Biological Recording Company founder and former FSC BioLinks Project Manager) sharing the successes, challenges, lessons learned and legacies of the project.

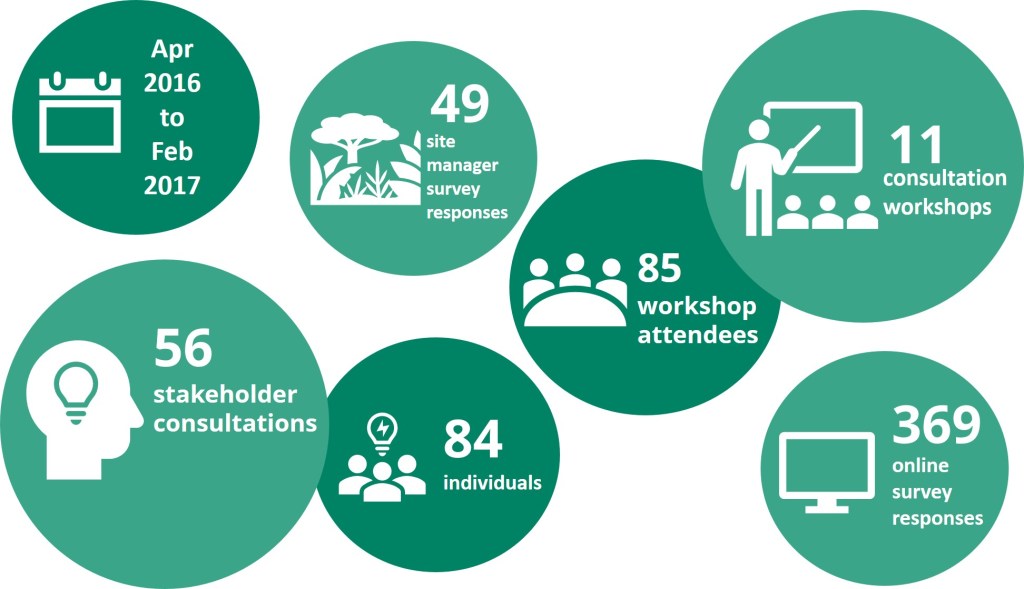

A 10-month development phase preceded the 5-year delivery phase of the FSC BioLinks project, taking place from April 2016 to January 2017 and funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. It included a comprehensive consultation to determine which species groups would be included in the project and where the training would take place, gathering information from sector professionals and potential volunteers.

Consultation activities included:

- 11 consultation workshops that engaged 85 individuals.

- 56 stakeholder consultations with sector organisations and groups.

- An online consultation survey that received 369 individual responses.

- A site manager survey that received 49 responses.

A detailed summary of the consultation results was published in the FSC BioLinks Consultation Report.

Identifying focus species groups

The project remit was to identify species groups that were both:

- Data deficient

- Difficult to identify

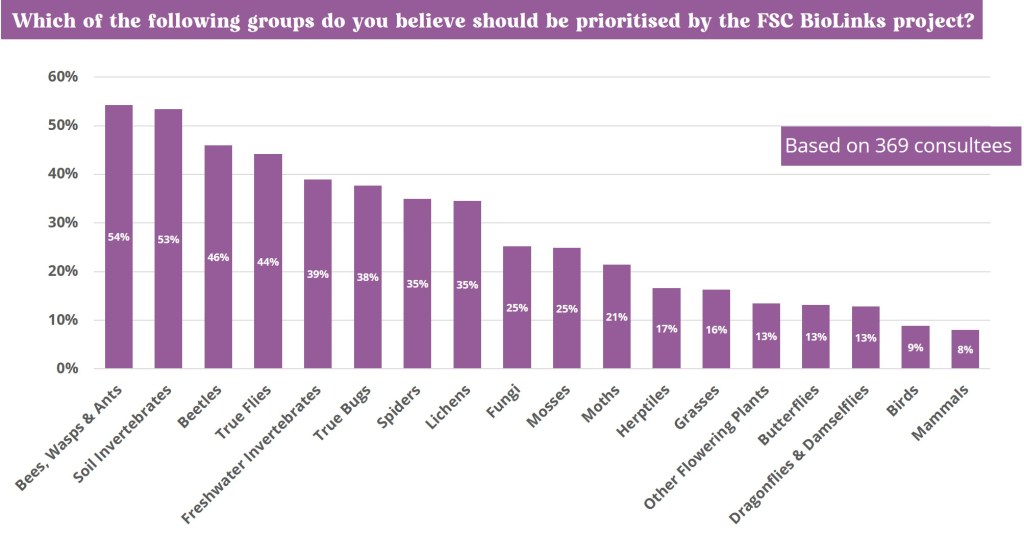

The subject of which species groups should be prioritised was explored in the consultation workshops and the online survey.

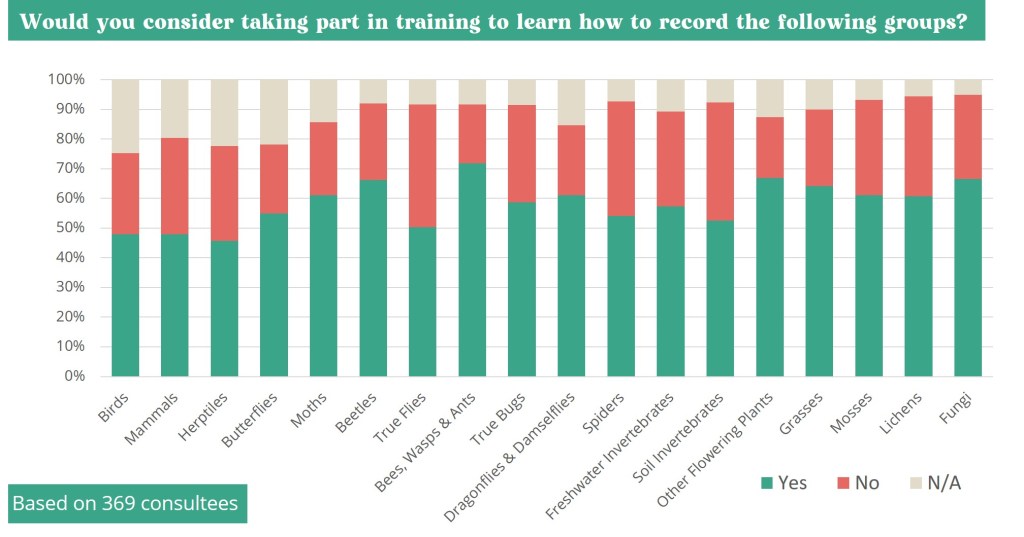

It was established that there was a reasonable level of demand for all species groups, with most of the lowest demand groups being those that are already relatively well covered through existing training programmes (likely due to the consultee’s greater experience in recording these groups) (see Figure 2).

Workshop consultees suggested that prioritisation should be based on factors such as ecological importance, seasonality, current training provision and synergy with existing projects. 12 groups were referenced repeatedly that matched the project criteria. Online survey respondents were also asked to indicate which species groups they felt should be prioritised (see Figure 3), helping to refine the list to 10 groups.

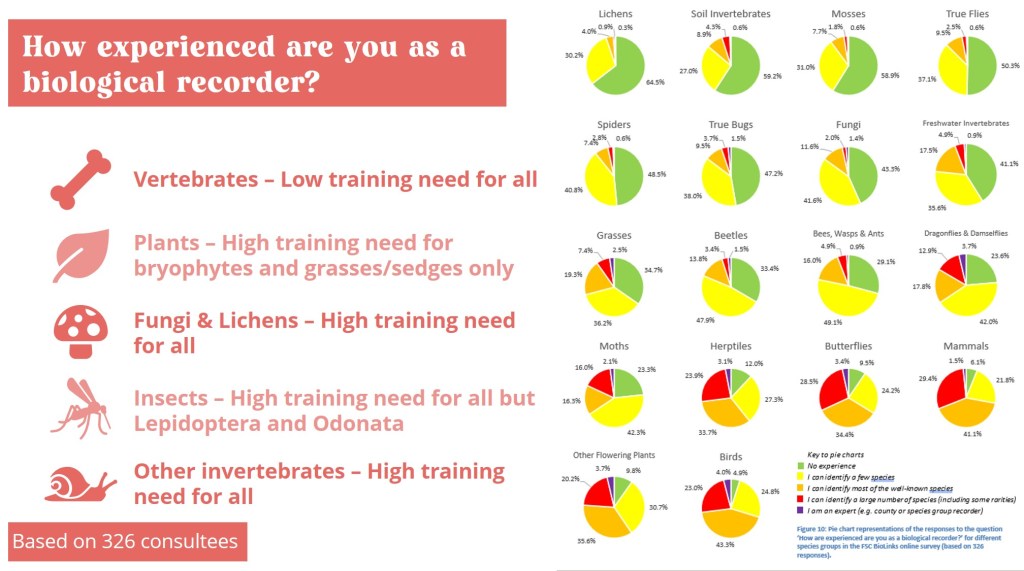

An analysis of current experience levels through the online survey confirmed that the groups with high priority also had fewer existing experienced recorders (see Figure 4).

To reduce the list of focus species groups to 8, it was decided that the project would have an invertebrate focus to reduce the cost of equipment and resources that would be needed to cover a more diverse range of focus species groups.

The following 8 focus species groups were identified for inclusion within the project:

- Aculeate hymenoptera (bees, ants and wasps)

- Arachnids (spiders, harvestmen and false scorpions)

- Beetles

- Freshwater invertebrates (riverflies and dragonflies/damselflies)

- Non-marine molluscs (slugs and snails)

- Soil invertebrates (earthworms, woodlice, centipedes and millipedes)

- True bugs

- True flies

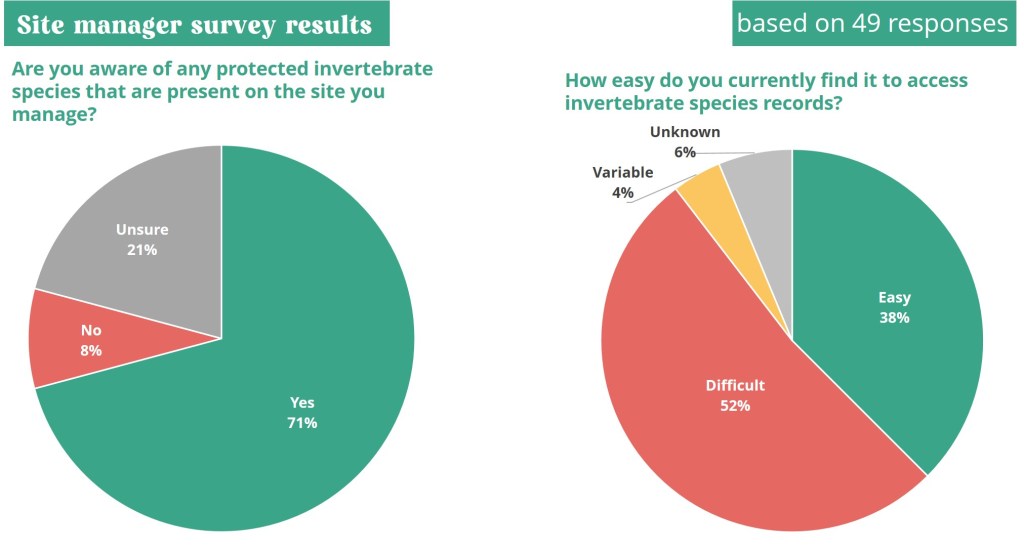

Site managers confirmed that they were aware of protected invertebrate species on the sites that they managed, but found it difficult to to access invertebrate species records (see Figure 5). This evidenced the need for more recording of invertebrates on these sites.

Although they were not included in the project training programme, the FSC BioLinks Consultation highlighted the need for future efforts to focus on:

- Fungi

- Lichens

- Mosses

- Grasses and Sedges

Identifying the locations

The BioLinks project would deliver training programmes within two regions (West Midlands and South East England) and aimed to facilitate identification training ‘hubs’ that would deliver two services to volunteers:

- Provision of a number of identification courses covering the focal taxa to allow the development of identification skills and knowledge.

- Support services for volunteers, such as access to microscopes, literature libraries, natural history collections and mentoring from experts or staff to build confidence and provide motivation.

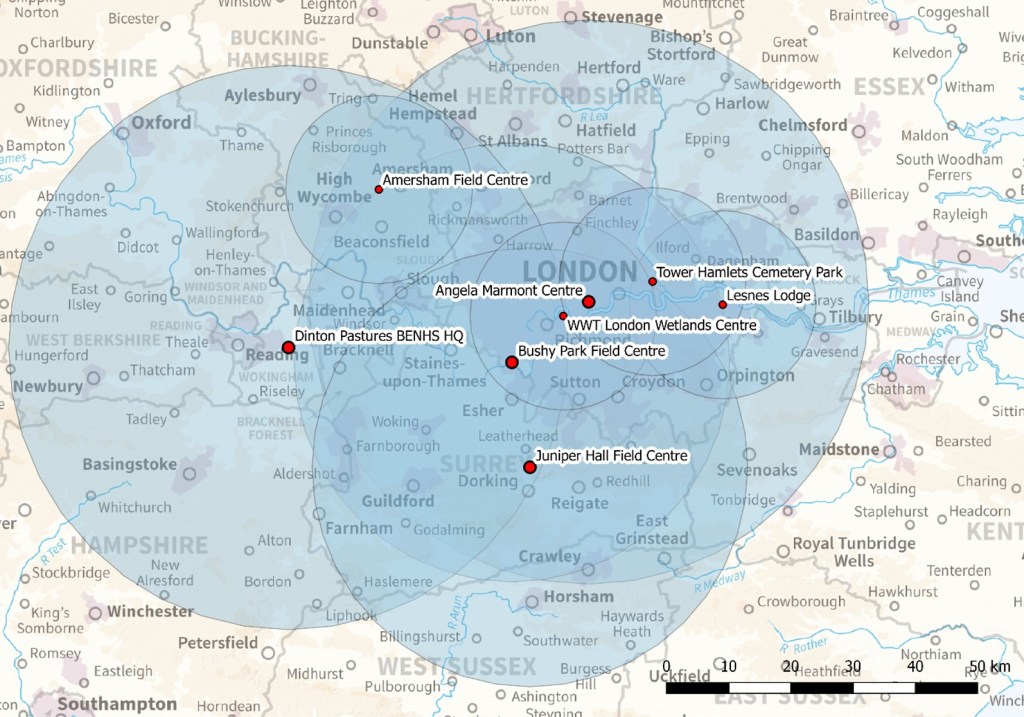

The consultation identified that the project should support existing training hubs, create new training hubs and utilise residential training centres within each of the two project regions (see Table 1).

| Hub type | West Midlands region | South East England region |

| Existing | FSC Preston Montford | BENHS Dinton Pastures |

| Emerging | FSC Bishops Wood | FSC London: Bushy Park |

| Residential | FSC Preston Montford | FSC Juniper Hall |

There was interest from a wide range of external training facilities so it was also decided that these could act as outreach training facilities and host introductory courses to help recruit local volunteers and encourage them to travel to the main hubs for further training (see Figure 6 for an example of the predicted project area and hubs within the South East England region).

Volunteer preferences

The consultation also informed who the training would be targeted at and how it would be delivered. An evidence need that was noticeably absent from the biodiversity training sector was information on learner preferences regarding the format and scheduling of training courses.

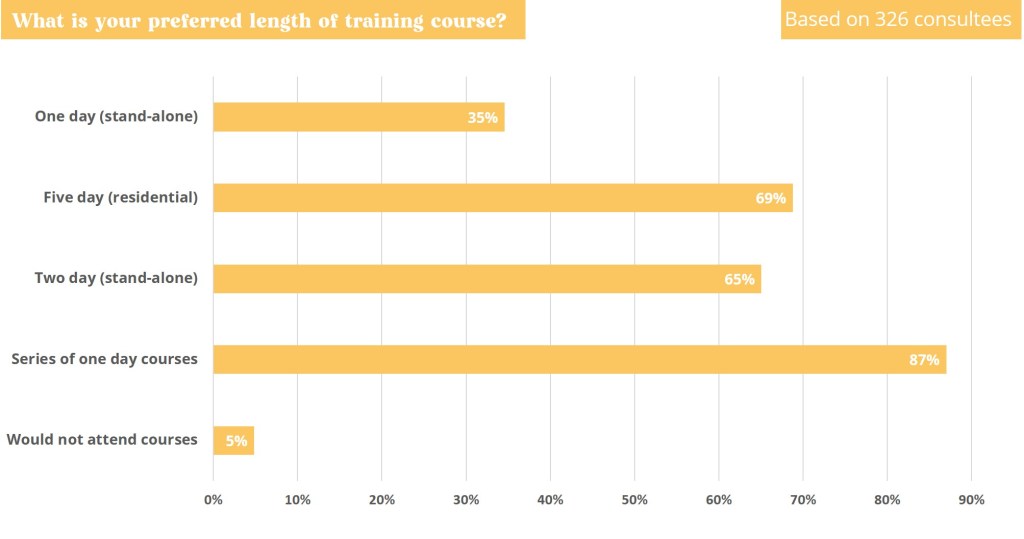

Online survey respondents showed a clear preference for training that allowed more time for knowledge and skill progression (see Figure 7), with a series of one-day courses being the most popular option and stand-alone one-day courses the least popular. This highlighted the need for a structured training programme that considered progression in a similar manner to professional CPD training programmes.

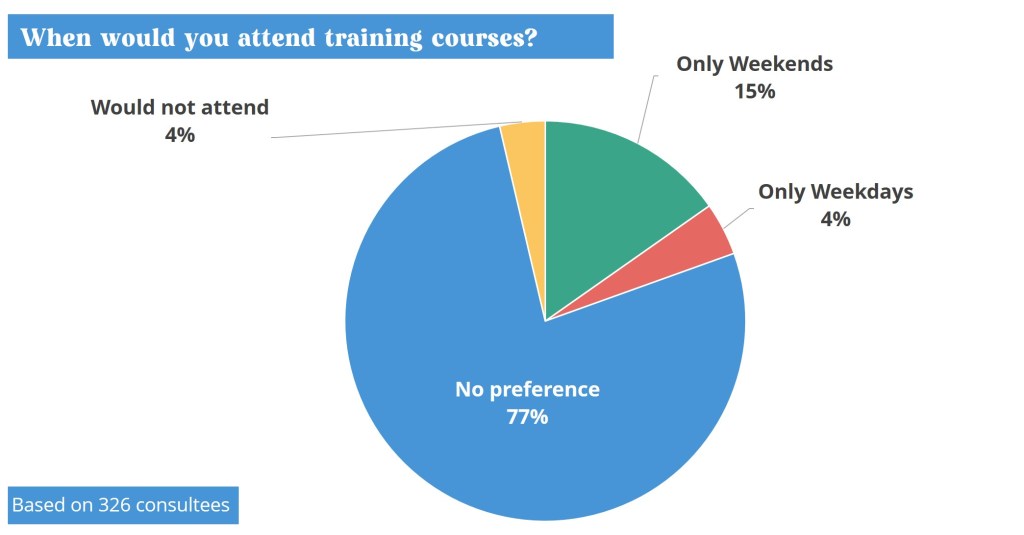

Sector professionals often articulated an assumption that training opportunities should be delivered during the weekend in order to ensure good attendance. The online survey demonstrated that this assumption was not true (see Figure 8), with 77% displaying no preference, 15% only weekends and 4% only weekdays. This highlighted the need for a variety of scheduling options to account for differing availability between individuals.

For example, when considering individuals working full-time:

- those working Monday to Friday may be attending as part of their CPD and may prefer weekday courses.

- those working Monday to Friday may be attending in their own time and prefer weekends.

- those working patterns other than Monday to Friday may prefer weekdays or weekends depending on their specific working pattern when the course is taking place and/or if they can attend as part of their CPD or not.

Structured training

Alongside the FSC BioLinks Consultation Report, the FSC BioLinks Development Plan For Training Provision was compiled. This plan incorporated both the preferences indicated by potential project participants and feedback from the relevant National Recording Schemes and Societies that were consulted.

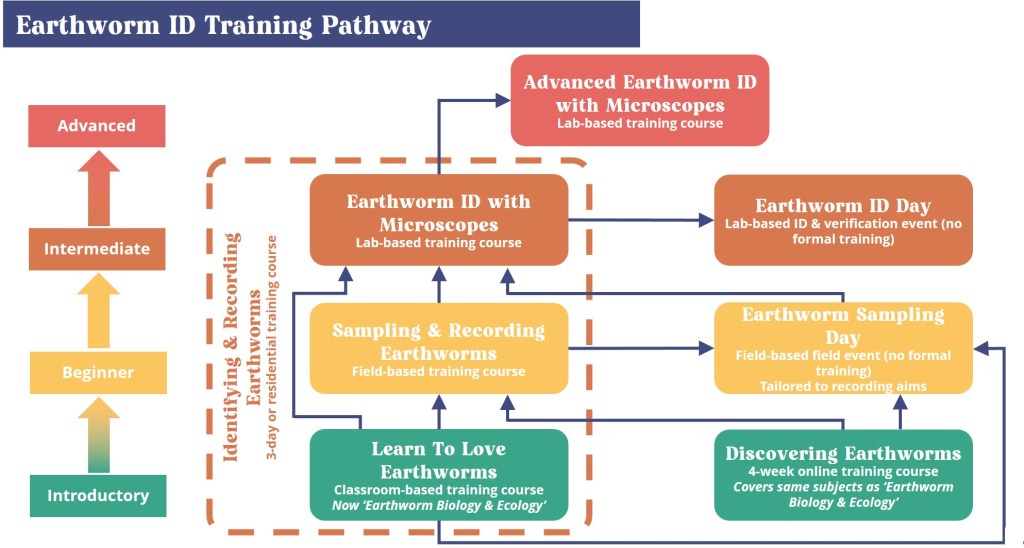

A levels system for classifying the courses within the training programme was created based on the Field Identification Skills Certificate (a botanical assessment created by the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland).

Seven levels were identified: General Public (not relevant to project activities), Introductory, Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, Regional Expert and National Expert. Within ‘The FSC BioLinks Volunteer Learning Pathway’ these levels were described in relation to learner knowledge, skills, confidence and motivation.

For each of the focus species groups identified for inclusion within the project, draft structured ID training pathways were created, identifying the courses that could be included and which levels these would sit within (see Figure 10 for earthworm example). These structured training pathways were not designed to be comprehensive (particularly for large species groups such as beetles, true bugs or true flies) and it was expected that they would evolve throughout and beyond the project. Provision of the courses within the pathways was not restricted to project activities, and other training providers were welcome to incorporate these courses within their training programmes so that BioLinks could focus on filling gaps.

Project Activity Plan

The consultation findings and training plan were pulled together into a project plan for a 5-year £1.6 million project that aimed to:

- Record under-recorded invertebrate species throughout the project regions.

- Train new and existing biological recorders in the ID of difficult-to-identify invertebrate groups.

- Strengthen the biological recording network by:

- producing publicly available resources.

- recruiting new volunteers for biological recording.

- working collaboratively and sharing lessons learned with the biodiversity sector.

The FSC BioLinks Project Activity Plan set out how this would be achieved through the delivery of a number of work packages arranged in 3 workstreams.

These would later be adapted (particularly in response to the Covid-19 pandemic) and organised into 8 workstreams (see figure 11) and will be explored in more detail in subsequent blog posts.

References

- Brown, K. D. (2018) FSC BioLinks Development Plan For Training Provision. Field Studies Council. https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/applied-ecology-resources/document/20230081529/

- Brown, K. D. (2017) FSC Biolinks Activity Plan. Field Studies Council. https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/applied-ecology-resources/document/20230030033/

- Brown, K. D. (2017) FSC BioLinks Consultation Report. Field Studies Council. https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/applied-ecology-resources/document/20203291194/