More Moths Please! Breeding and Reintroducing the Dark Bordered Beauty

The Dark Bordered Beauty (Epione vespertaria) is a striking moth that, within the UK, is currently restricted to just three sites; two in Scotland and one in York. To help restore this species and safeguard it for the future, RZSS, in partnership with the Rare Invertebrates in the Cairngorms Project, is running a conservation breeding programme providing hundreds of eggs, caterpillars, and moths for release into new sites in the Cairngorms National Park. Helen will give more information on this remarkably rare species, provide the latest news on how the conservation programme is progressing, and detail some of the challenges faced by her team in trying to breed a moth species that is so rarely seen in the wild

Q&A with Georgina Lindsay

Georgina Lindsay is a conservation manager at the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS). She manages all of RZSS’ native invertebrate breeding and reintroduction programmes, including dark bordered beauty moths, pine hoverflies, medicinal leeches, and pond mud snails, as well as the field surveys for species such as blood red longhorn beetles and small scabious mining bees. She also oversees the Biodiversity Action Plan for Highland Wildlife Park, including areas such as forestry management and wading bird nest monitoring.

1. Do Dark-bordered Beauty Moth larvae only feed on Aspen? How do we know?

We know that Dark-bordered Beauty Moth larvae feed on Aspen (Populus tremula) at the two Scotland sites because they are almost exclusively found on this host plant there. At the one site in England, in Yorkshire, Creeping Willow (Salix repens) appears to be an alternative known host plant for the larvae. All our conservation breeding work in Scotland has so far used Aspen but we are interested to potentially trial feeding of Scottish larvae on Creeping Willow in the future.

2. How big of a stand of Aspen is needed to support a Dark-bordered Beauty Moth population?

The short answer is we don’t know. Aspen stands size varies between all the sites we work on – both founder sites and release sites. At the Strensall site in Yorkshire, there is no Aspen, and they rely on Creeping Willow, which is an alternative larval food plant here. In the conservation breeding programme, we’re finding that the caterpillars only need a relatively small amount of Aspen to grow to maturity. At our facility we’ve found that 20 caterpillars can be easily supported by six small suckering Aspen trees. This suggest that it’s not the quantity of food per se which is the limiting factor behind their scarce distribution, but instead that disconnected aspen stands are limiting natural dispersal and the colonisation of new sites.

3. Do Dark-bordered Beauty Moth larva only pupate in moss?

In our conservation breeding programme for the Dark-bordered Beauty Moth, we used a bed of Sphagnum moss to provide an area for the caterpillars to pupate. The choice to do this was informed by using similar substrate to that found at the Strathspey founder site. That being the case, it is certainly possible that the moth can pupate on or in other substrates. We have noticed in some of our enclosures that the larvae have successfully pupated on bare ground. It’s also possible that they can pupate within soil, however we have not trialled this due to foreseen difficulties with re-locating pupae within the soil (given they might burrow down into it).

4. Is there a pheromone lure for Dark-bordered Beauty Moths?

Not at the moment. The process of creating a pheromone lure can be quite complex; for example, you need to collect a lot of adult individuals. It’s not something we have spoken much about yet in the context of the Dark-bordered Beauty Moth because so far we have had success with locating adults at known sites using standard light-trapping techniques and transects. Pheromone luring could potentially be a possibility down the line though.

5. Is research into the ecology of this species ongoing?

Whilst my personal focus is on the conservation breeding and reintroduction programme, as a team and steering group focused on conserving the Dark-bordered Beauty Moth we are very keen to find out everything there is to know about the ecology of this moth. Interesting potential ecological research questions are often brought up in steering group meetings. For example, nearly all the current knowledge of feeding preferences is based on observation of the larvae ex situ in the breeding facility. How might feeding preferences differ in situ? If any prospective Master’s or PhD students are interested in working with us to answer questions like this we would welcome you to get in touch. You can contact the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) at conservation@rzss.org.uk.

Further Info

- RZSS Conservation: https://www.rzss.org.uk/conservation

- The Pine Hoverfly: Bringing Them Back From The Brink Of Extinction entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2023/03/23/pine-hoverfly/

- Invertebrate Translocation and Reintroduction Virtual Symposium: https://courses.biologicalrecording.co.uk/courses/invertebrate-translocation-virtual-symposium

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

Protected: Terrestrial Harvestmen

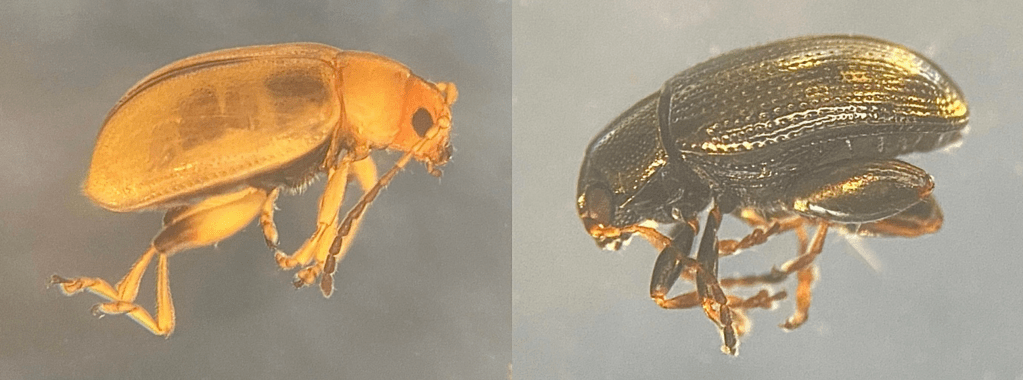

Getting to Know Weevils

Weevils are one of the UK’s most diverse groups of beetles, with around 550 species currently known to occur here. You will find weevils every time you go and look for insects, but they have a reputation for being difficult to identify. In this talk, Mark introduces the different groups present in the UK, and outlines how you can get to know them better.

Q&A with Mark Gurney

Mark Gurney is one of the organisers of the UK Weevil Recording Scheme and is responsible for the production and maintenance of a range of identification guides for the British species.

1. How can I identify a weevil I have found?

I’ve produced a range of identification guides for the different groups of UK weevils, all of which you can find here: tinyurl.com/weevilguides. My photo albums for UK weevils may also be helpful and can be found here: tinyurl.com/weevilalbums. There is also a Facebook page (not created by me!) where you can pose identification queries: Weevils of Britain. If you have a photo you can add it as a record to iNaturalist or iRecord.

2. What’s the best time of year to look for weevils?

Looking at the group as a whole, the annual peak in diversity, numbers, and activity is around April-May-June. That being said, if you only look during the Spring there are some species you may miss, and many species have population peaks later in the year. Ultimately, there are weevils to be found at any time of year. This even includes during winter as most species live over winter as adults. You have to put in more effort to find weevils during winter, though, as those that are around are less active. Grubbing around beneath vegetation or within grass tussocks is one method that can work well in the colder months, as can sifting leaf litter.

3. What do weevils eat?

As larvae, many weevils feed on a specific group of closely related plants (e.g. one species, genus or family of plants). Knowledge of host plant can therefore be a good clue for identifying the weevil species found. There are, however, some groups of weevils which are more generalist ‘polyphagous’ feeders, such as the broad-nosed weevils (family: Curculionidae; subfamily: Entiminae). Adult weevils may remain on the same plant they fed on as larvae, but they can and do move to other plants. For example, a species which feeds on legumes in summer might move to shrubs during autumn for shelter over the winter.

4. Are there any non-native weevil species in the UK?

Currently we recognise 547 total species of weevil (excluding the bark beetles) as established in the UK. At least 50 of these are non-native. Many of the non-native species are broad-nosed weevils or weevils associated with decaying wood and timber. A lot of new species are coming in through the horticultural trade.

5. How well studied and recorded are weevils?

There is still loads for us to learn and find. Speaking personally, it’s a bad year if I don’t find at least one weevil species new to my county, just by going around looking in the area where I live. The opportunity for anyone to make a difference by contributing is huge. By simply putting your records on iRecord or iNaturalist you will undoubtedly be putting new dots on the maps. There are also likely a fair few new species waiting to be found in the UK, both new arrivals and long-overlooked native species. With climate change and ever-increasing global trade, we are finding new weevil species to the UK every year. There are also some gaps regarding feeding preferences, i.e., there are some species for which we do not currently know the plants the weevil feeds on, so opportunity to get involved there too.

Further Info

- Mark Gurney’s weevil identification guides: tinyurl.com/weevilguides

- Mark Gurney’s weevil photo albums: tinyurl.com/weevilalbums

- Weevils of Britain Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/142476362952752/

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

From Strandline to Science: The Journey of a Shark Eggcase

The Great Eggcase Hunt encourages people to get out on the beach in search of mermaids purses – the eggcases of sharks and skate. Each species has a distinct design so, once found, you can identify which species it once belonged to, before recording them to the Shark Trust. Find out how the Great Eggcase Hunt has evolved over the past 22 years, what it has discovered during that time, and how you can get involved as a citizen scientist.

Q&A with Cat Gordon

Cat Gordon is the Senior Conservation Officer at the Shark Trust – a UK conservation charity working globally to safeguard the future of sharks, skates and rays. She leads the Community Engagement programme and is responsible for citizen science initiatives such as the Great Eggcase Hunt and the Basking Shark Project. She’s previously been involved in developing a number of conservation planning documents for highly threatened species, and is now working on developing a new project called Living with Sharks.

1. What triggers eggcases to pop open?

When the developing shark or skate is ready to emerge, the eggcase will naturally open along the top seam (between the upper two horns or upper tendrils). The growth of the embryo within the eggcase causes the capsule to pop open (pre-opening) once the developing shark or skate reaches the appropriate size – almost like they’re bursting out. They will then need to wiggle their way out of the capsule to break free. The eggcase will only ever open naturally along that top seam. If you find an eggcase with a hole or split elsewhere this will have been caused by predation, e.g., by a crab or mollusc, or if washed ashore it could be from a bird pecking the eggcase capsule.

2. What determines the shape and size of an eggcase?

The general shape is determined by which taxonomic family or order it belongs to. There are five orders and 13 families that are oviparous (egg-laying). However, the exact shape and features (e.g. whether there are keels or tendrils) are unique to each species. Skate eggcases are usually square or rectangular in shape, often with a pointed horn on each corner; catshark eggcases are usually oblong shaped, almost like a bowling pin and may have tendrils extending from the corners; horn sharks have spiral shaped eggcases like a corkscrew; carpetsharks are rounder in shape and may have very short horns; and chimaeras are spindle or leaf shaped.

Beyond that, it is also worth noting that environmental conditions (e.g. water temperature) may impact characteristics of the eggcase, particularly size and colour, with the latter being quite variable amongst the eggcases of some species (such as the Smallspotted Catshark). It is also true that the larger species generally have larger eggcases, for example, the Flapper Skate reaches 2-3m in length and its eggcase capsule is amongst the largest that can be found at around 20cm.

3. Is it okay to take eggcases home and keep them?

As far as we know, empty eggcases do not serve a secondary purpose in the seashore environment, unlike seaweed which decomposes and provides vital habitats and food sources for many organisms, as well as contributing to nutrient cycling. In fact, eggcases don’t seem to break down at all, we’ve had many eggcase hunters attempt to compost them in home compost bins, but they come out the same as they go in! We therefore believe it’s acceptable to take empty eggcases home if you wish to and if anything, it will prevent duplicate counting if someone finds and reports that same eggcase after you. That being said, if taking part in the Great Eggcase Hunt, you never have to collect the eggcases, and so it is always personal choice.

If you do wish to collect eggcases, make sure you are 100% certain they are empty. Admittedly, the shark/skate embryo inside doesn’t stand a good chance of surviving once its eggcase has washed up on the beach, but there is always a chance so we’d advice that you return any you suspect have content to the sea, ideally anchored down in a secure spot.

4. Is it worth uploading photos of eggcases that you saw several years ago?

Absolutely! If you’ve got photos of an eggcase with a reliable date and location, you can record it to the Great Eggcase Hunt at www.sharktrust.org/greateggcasehunt or via the Shark Trust citizen science app, regardless of when it was from. You can also submit eggcases from anywhere in the world!

5. What are the main threats to sharks and rays in British waters?

The main threat to sharks and rays is overfishing. That is true irrespective of which part of the ocean they are in. Globally, a third of all sharks, rays and chimaeras are threatened with extinction risk, and this is primarily due to overfishing. Sharks are inherently vulnerable as they are long lived, late to mature, and produce few young, meaning they are unable to replenish their populations quickly. In addition, many sharks and rays are highly migratory and so may cross multiple country borders. International collaboration is therefore required through international fishing agreements and coordination through Regional Fishery Management Organisation bodies to ensure they are suitably managed across their range. There are other threats to sharks and rays, such as habitat destruction and pollution, but they are secondary to overfishing.

Literature References

- Ellis et al. (2024) ‘The distribution of the juvenile stages and eggcases of skates (Rajidae) around the British Isles’: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aqc.4149

- Gordon et al. (2016) ‘Descriptions and revised key to the eggcases of the skates (Rajiformes: Rajidae) and catsharks (Carcharhiniformes: Scyliorhinidae) of the British Isles’: https://www.mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.4150.3.2

Further Info

- Shark Trust: www.sharktrust.org

- Great Eggcase Hunt: www.sharktrust.org/greateggcasehunt

- Eggcase ID guidance: https://www.sharktrust.org/geh-id

- Eggcase training guides: https://www.sharktrust.org/geh-training

- Eggcase Recording Hub: https://recording.sharktrust.org/ (App Store: https://apps.apple.com/sr/app/the-shark-trust/id159770154; Google Play Store: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.sharktrust.sharktrust&gl=GB)

- The Great Eggcase Hunt Celebrating 20 Years! report: https://www.sharktrust.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=c6b91890-428b-41f9-98e9-db73a86ff20a&_gl=1*1mmmkdf*_up*MQ..*_gs*MQ..&gclid=CjwKCAjwup3HBhAAEiwA7euZug_TbK-OG9S8JwQ6zFUrR2ik_Fc_5YoMA59kjtILehrFwWYbP1eejxoCFNgQAvD_BwE&gbraid=0AAAAADLDCVUJ-5t-os8sDwO7WGseLvxb_

- FSC WildID fold-out guide for shark and ray egg cases: https://www.nhbs.com/shark-and-skate-eggcases-book

- Important Shark and Ray Areas (ISRAs) E-Atlas: https://sharkrayareas.org/e-atlas/

marineLIVE

marineLIVE webinars feature guest marine biologists talking about their research into the various organisms that inhabit our seas and oceans, and the threats that they face. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for marine life is all that’s required!

- Upcoming marineLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/cc/marinelive-webinars-3182319

- Donate to marineLIVE: https://gofund.me/fe084e0f

- marineLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/marinelive-blog/

- marineLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE-t2dzcoX59iR41WnEf21fg&feature=shared

marineLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company with funding from the British Ecological Society.

- Explore upcoming events and training opportunities from the Biological Recording Company: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/o/the-biological-recording-company-35982868173

- Check out the British Ecological Society website for more information on membership, events, publications and special interest groups: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/

Learn more about British wildlife

Syrph-ing the Continents: Hoverflies, Our Unsung Agricultural Heroes

Syrphidae, commonly known as hover flies or flower flies, are an important family of true flies. This talk explored the diverse ecosystem services these flies provide throughout their life cycle, from pest control to pollination. A major focus is on hoverflies’ remarkable ability to migrate long distances, distributing these services across vast geographic areas.

While many questions remain about the migratory behaviour of species within this family, recent advances in technology and research methods are discussed that offer promising new insights. These developments give us hope for what lies ahead in uncovering the secrets of these small but mighty insects.

Q&A with Samm Reynolds

Samm Reynolds is a PhD candidate at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. She studies native pollinator conservation in agriculture throughout southern Ontario and has a particular interest in native bees and syrphids (hover flies). Her goal is to understand pollinator-habitat interactions at a species level and to bring this research to the public through education campaigns and pushing for improved pollinator protection policy.

1. How far do hoverflies migrate?

The longest distance recorded for single hoverfly migration, based on stable isotope analysis, is a staggering 3,000 kilometres. This puts the maximum distance observed for hoverfly migration on par with that observed for the migration of dragonflies and butterflies. Remember that wind plays a crucial role in facilitating such long-distance movement – these migrations are definitely not entirely self-propelled! Such long-distance migration is far from the case for all hoverfly migrations, of course, and research generally suggests that the distance migrated is highly variable both between and within species.

2. Do both sexes of hoverflies migrate?

There is evidence to suggest that it is predominantly female hoverflies who migrate, or at least who migrate the furthest. There are definitely some males that migrate, but evidence shows that they aren’t as well equipped for long distant flying. This is because females are often more cold tolerant and also utilise something called ‘oogenesis-flight syndrome’ whereby they build up fat deposits rather than developing their ovaries which gives them long-term endurance for long-distance flights. When collecting hoverflies mid-migration, whilst the exact sex ratio varies by species, ratios are most often skewed towards females, especially at the “end point” of their migration.

3. How can we make agricultural habitats more welcoming for hoverflies?

The primary recommendation that we are making for agriculture right now is to maintain semi-natural habitats as part of farmland. Features like hedgerows are immensely useful for hoverflies, as are piles of rotting wood (which should ideally be left out, rather than cleared away), as are diverse local floral resources, as are forest edges. It is often feasible to conserve these features even on intensely farmed plots of land by constructing and maintaining them on marginal land, small pockets and along field boundaries. It’s also recommended to provide flowering resources for the entire season, hoverflies may not often stray too far and so having access to floral resources for their whole life cycle within a fairly small radius is really important.

Literature References

- Reynolds et al. (2024) ‘A comprehensive review of long-distance hover fly migration (Diptera: Syrphidae)’: https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/een.13373

- Jeekel and Overbeek (1968) ‘A migratory flight of hover-flies (Diptera, Syrphidae) observed in Austria. Beaufortia’: https://repository.naturalis.nl/pub/505147/BEAU1968015196001.pdf

- Shannon (1926) ‘A preliminary report on the seasonal migrations of insects’: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25004127.pdf

- Menz et al. (2019) ‘Quantification of migrant hoverfly movements (Diptera: Syrphidae) on the West coast of North America’: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsos.190153

- Stefanescu et al. (2013) ‘Multi-generational long-distance migration of insects: studying the painted lady butterfly in the Western Palaearctic’: https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/21064/1/N021064PP.pdf

- Jia et al. (2022) ‘Windborne migration amplifies insect-mediated pollination services’: https://elifesciences.org/articles/76230.pdf

- Kanazawa et al. (2015) ‘First migration record of chestnut Tiger butterfly, Parantica sita niphonica (Moore, 1883) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Danainae) from Japan to Hong Kong and longest recorded movement by the species’: https://bioone.org/journals/The-Pan-Pacific-Entomologist/volume-91/issue-1/2014-91.1.091/First-migration-record-of-Chestnut-Tiger-Butterfly-iParantica-sita-niphonica/10.3956/2014-91.1.091.short

- Bauer et al. (2024) ‘Monitoring aerial insect biodiversity: A radar perspective’: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rstb.2023.0113

- Hu et al. (2016) ‘Mass seasonal bioflows of high-flying insect migrants’: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.aah4379

- Gao et al. (2020) ‘Adaptive strategies of high-flying migratory hoverflies in response to wind currents’: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2020.0406

- Wotton et al. (2019) ‘Mass seasonal migrations of hoverflies provide extensive pollina- tion and crop protection services’: https://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdfExtended/S0960-9822(19)30605-0

- Ouin et al. (2011) ‘Can deuterium stable isotope values be used to assign the geographic origin of an auxiliary hoverfly in south-western France?: Geographic origin of an auxiliary hoverfly’: https://analyticalsciencejournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/rcm.5127

- Clem et al. (2023) ‘Insights into natal origins of migratory Nearctic hover flies (Diptera: Syrphidae): new evidence from stable isotope (δ 2 H) assignment analyses’: https://nsojournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/ecog.06465

- Dällenbach et al. (2018) ‘Higher flight activity in the offspring of migrants compared to residents in a migratory insect’: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.2017.2829

- Massy et al. (2021) ‘Hoverflies use a time-compensated sun compass to orientate during autumn migration’: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2021.1805

- Svensson and Janzon (1984) ‘Why does the hoverfly Metasyrphus corollae migrate?’: https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1984.tb00856.x

- Clem et al. (2022) ‘Do Nearctic hover flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) engage in long-distance migration? An assessment of evidence and mechanisms’: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ecm.1542

- Hart and Bale (1997) ‘Cold tolerance of the aphid predator Episyrphus balteatus (DeGeer) (Diptera, Syrphidae)’: https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-3032.1997.tb01177.x

- Hondelmann and Poehling (2007) ‘Diapause and overwintering of the hoverfly Episyrphus balteatus’: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00568.x

- Doyle et al. (2022) ‘Genome-wide transcriptomic changes reveal the genetic pathways involved in insect migration’: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/mec.16588

- Francuski et al. (2013) ‘Landscape genetics and spatial pattern of phenotypic variation of Eristalis tenax across Europe’: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jzs.12017

- Hondelmann et al. (2005) ‘Restriction fragment length polymorphisms of different DNA regions as genetic markers in the hoverfly Episyrphus balteatus (Diptera: Syrphidae)’: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bulletin-of-entomological-research/article/abs/restriction-fragment-length-polymorphisms-of-different-dna-regions-as-genetic-markers-in-the-hoverfly-episyrphus-balteatus-diptera-syrphidae/C1CD4F21556C1F978808841AF4BD24DC

- Raymond et al. (2013) ‘Lack of genetic differentiation between contrasted overwintering strategies of a Major Pest predator Episyrphus balteatus (Diptera: Syrphidae): implications for biocontrol’: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0072997&type=printable

- Raymond et al. (2013) ‘Migration and dispersal may drive to high genetic variation and significant genetic mixing: The case of two agriculturally important, continental hoverflies (Episyrphus balteatus and Sphaerophoria scripta)’: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0072997&type=printable

- Liu et al. (2019) ‘Genome-wide developed microsatellites reveal a weak population differentiation in the hoverfly Eupeodes corollae (Diptera: Syrphidae) across China’: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0215888&type=printable

- Davis et al. (2023) ‘Crop-pollinating Diptera have diverse diets and habitat needs in both larval and adult stages’: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/eap.2859

- Orford et al. (2015) ‘The forgotten flies: the importance of non-syrphid Diptera as pollinators’: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2014.2934

- Landry and Parrott (2016) ‘Could the lateral transfer of nutrients by outbreaking insects lead to consequential landscape-scale effects?’: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/ecs2.1265

- Fisler and Marcacci (2022) ‘Tens of thousands of migrating hoverflies found dead on a strandline in the south of France’: https://publications.goettingen-research-online.de/handle/2/125027

- Lv et al. (2023) ‘Changing patterns of the east Asian monsoon drive shifts in migration and abundance of a globally important rice pest’: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/gcb.16636

Further Info

- The Most Remarkable Migrants of All: The Fascinating World of Fly Migration entoLIVE: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2023/03/13/fly-migration/

- Syrphidae migration video: https://youtu.be/30u0dXZ0bjo

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

Seagrass Conservation: Growing #GenerationRestoration in Europe

Seagrass conservation plays a critical role in maintaining planetary health. This presentation explores this role, before turning to how the recently founded European Seagrass Restoration Alliance (ESRA) is seeking to overcome existing barriers to the conservation, restoration and re-establishment of European seagrass meadows by providing a platform for the ESRA community to collaborate and engage in knowledge exchange. ESRA was founded to meet noth the challenges and opportunities presented by UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, and the EU Nature Restoration Law. In order to deliver on current marine restoration ambitions, unprecedented transnational collaboration, and the rapid development and deployment of novel innovations will be required.

Q&A with Dr Richard Lilley

Dr Richard Lilley started his research career studying sustainable supply chain management in small-scale capture fisheries. Here, seafood supply chains – on which local food security depends – are reliant on healthy natural coral reefs, seagrass meadows and mangrove forests. Becoming fascinated by the critical importance of seagrass meadows in particular, as both havens for biodiversity and nursery grounds for many commercially important fish species, Richard first cofounded a UK NGO called Project Seagrass (2013), before turning his attention to scaling up seagrass restoration in Europe (2024).

1. What is the minimum salinity for seagrass?

The answer depends on how you define the term seagrass. Different definitions mean that some scientists recognise around 60 species of seagrass worldwide whereas others recognise 72. Following the strict definition, seagrasses are flowering plant species which complete their entire reproductive cycle within the marine environment.

However, some scientists also include plant species which are not fully marine and are found in more brackish environments, e.g., estuaries. I explained in the talk that in Europe we generally recognise four species of seagrass (Posidonia oceanica, Cymodocea nodosa, Zostera marina and Zotera noltii). If you choose to follow a more expansive definition of seagrass then you could add a few extra species to that list, e.g. Ruppia maritima. These species are those that tend to be found in the freshwater-saltwater transition zone, places like estuaries or saltmarshes.

2. How are seagrass meadows designated for protection?

Legal protection for seagrass meadows varies by country. Sometimes it’s automatic. For example, in Scotland, all seagrass meadows are automatically protected as ‘Priority Marine Features’. However, for the meadow to qualify as a ‘feature’ it needs to cover an area of at least 5 metres by 5 metres in area – it can’t just be a single transient plant. Other countries have different laws. And, often the process of designation is a frustrating one. One unique challenge with designating seagrass meadows for areal protection is that some meadows move slowly over time due to the dynamism of the underlying sediment. Thus, the edges of a meadow may shift, shrink or expand over a span of years. This shifting process has been recognised for some of the Zostera noltii and Zostera marina meadows in British waters. However, it is less of a problem in the Mediterranean with Posidonia oceanica seagrass meadows because that species is very robust, slow-growing and long-lived, hence Posidonia oceanica meadows tend to have clear and relatively fixed edges.

3. What factors determine which seagrass species grow where?

It depends on many things. On a local scale, the most important factor is probably light availability, as regulated by water clarity, which is in turn determined by the amount of sediment in the water column. Posidonia oceanica can be found up to depths of 50 metres in the clearest waters of the Mediterranean, in contrast Zostera noltii and Zostera marina might only be found down to around 1–2 metres in the turbid mouths of major European estuaries or even in the intertidal zone. At a broader scale, tidal range is another key factor. The Mediterranean famously only has a tiny tidal range, hence in this environment there is relatively little physical stress imposed on seagrasses by the movement of water. This contrasts with, for example, the Atlantic, where the tidal range is much greater and therefore there is constant turbulence in the water to which seagrasses must adapt. Tidal differences and the availability of light for photosynthesis are key factor as to why the Mediterranean features a different dominant seagrass species to the coasts of the British Isles.

4. Is climate change negatively affecting the health of European seagrass meadows?

Yes, unfortunately, anthropogenic climate change is clearly impacting our seagrass meadows. That is because seagrass meadow persistence at a given site is dependent on the ambient water temperature. At some seagrass sites which are at the southern edge of a seagrass species ranges, we are seeing notable shifts in the seagrass community composition as warming waters begin to favour certain species over others. In Étang de Berre in France, for example, the dominant species prior to the 1960s was Zostera marina. This lagoon is right at the southern edge of Zostera marina’s global range, so as the climate has warmed, Zostera marina has notably declined at the site and has been replaced by the more warmth-tolerant Zostera noltii. Conversations are now being had, from a restoration perspective, about whether restoring Zostera marina beds is a worthwhile venture here. In a few decades, might the waters be simply too warm in summer for it to survive?

5. Has active restoration of seagrass meadows been successful so far?

It depends on how you qualify success. In terms of ecological success – i.e. has the restoration worked? – the success rate is variable. Some projects see excellent outcomes, e.g. >90% survival of seedlings after the first year of planting. Other projects have had very little success so far. It is worth nothing though that many of these projects are still in their infancy. What is consistently exciting is that success by other metrics, particularly in terms of civic engagement and public involvement with restoration and marine stewardship, seems to be getting better all the time. More and more people are being connected with ecosystem restoration every year. At least in the early years of these projects, this is arguably a more important goal. Restoration is always experimental in nature, and some failures should be expected along the journey. We need to be better embracing uncertainty in marine restoration which means shifting from fixed goals to more flexible outcomes. In my opinion the path to eventual long-term success is facilitated by the engagement of a community of dedicated restoration practitioners and we are excited that this community is steadily growing.

Literature References

- Unsworth et al. (2022) ‘The planetary role of seagrass conservation’: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abq6923

- Unsworth et al. (2018) ‘Seagrass meadows support global fisheries production’: https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12566

- Unsworth and Cullen (2010) ‘Recognising the necessity for Indo-Pacific seagrass conservation’: https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12566

- Preston et al. (2025) ‘Seascape connectivity: evidence, knowledge gaps and implications for temperate coastal ecosystem restoration practice and policy’: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44183-025-00128-3

- Wedding et al. (2025) ‘Five ways seascape ecology can help to achieve marine restoration goals’: https://research.rug.nl/en/publications/five-ways-seascape-ecology-can-help-to-achieve-marine-restoration

Further Info

- The Seagrass Consortium: https://www.seagrassconsortium.org/

- European Seagrass Restoration Alliance (ESRA): https://esra-europe.eu/

- Project Seagrass: https://www.projectseagrass.org/

- The Sea Rangers: https://searangers.org/

- Seagrass Spotter: https://seagrassspotter.org/

- Seagrass Restorer: https://seagrassrestorer.org/

- Society for Ecological Restoration Marine Restoration Working Group: https://ser-europe.org/mrwg/

- BiodivRestore Knowledge Hub: https://www.biodiversa.eu/engagement/biodivrestore-knowledge-hub/

- The unexpected, underwater plant fighting climate change (TED Talk): https://www.ted.com/talks/carlos_m_duarte_the_unexpected_underwater_plant_fighting_climate_change

- From Roots to Recovery: Welsh Capital to host symposium Integrating Communities, Science, and Action for UK Seagrass: https://www.projectseagrass.org/blogs/conferences/from-roots-to-recovery-welsh-capital-to-host-symposium-integrating-communities-science-and-action-for-uk-seagrass/

- Etang de Berre website: https://etangdeberre.org/

- Lewis Michael Jefferies photography: https://lewismjefferies.com/

- The Ocean Agency, Ocean Image Bank: https://www.theoceanagency.org/ocean-image-bank

marineLIVE

marineLIVE webinars feature guest marine biologists talking about their research into the various organisms that inhabit our seas and oceans, and the threats that they face. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for marine life is all that’s required!

- Upcoming marineLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/cc/marinelive-webinars-3182319

- Donate to marineLIVE: https://gofund.me/fe084e0f

- marineLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/marinelive-blog/

- marineLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE-t2dzcoX59iR41WnEf21fg&feature=shared

marineLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company with funding from the British Ecological Society.

- Explore upcoming events and training opportunities from the Biological Recording Company: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/o/the-biological-recording-company-35982868173

- Check out the British Ecological Society website for more information on membership, events, publications and special interest groups: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/

Learn more about British wildlife

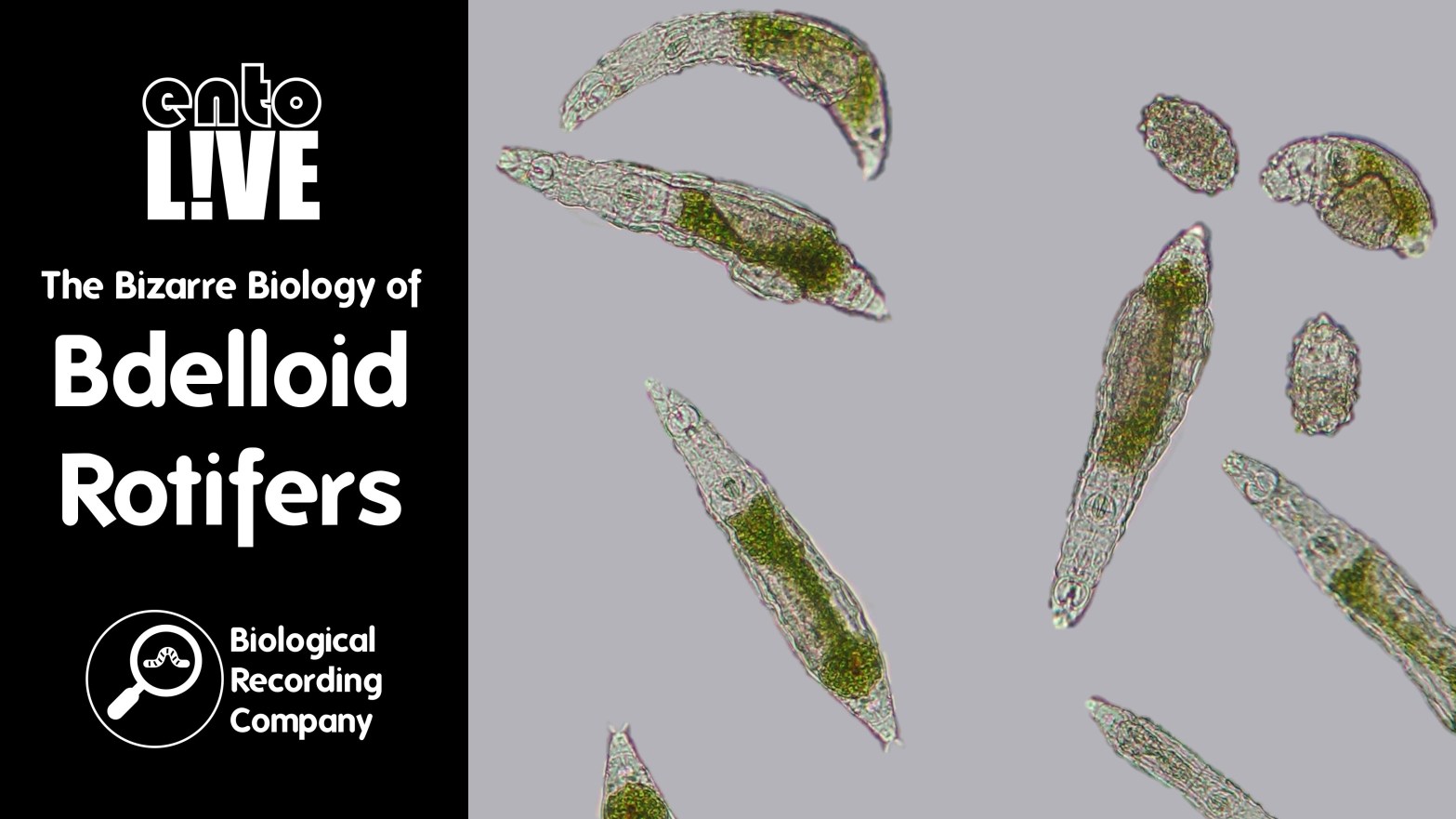

The Bizarre Biology of Bdelloid Rotifers

Bdelloid rotifers are tiny filter-feeding animals that live in freshwater habitats worldwide: in ponds, streams and lakes, even where the water sometimes dries up or freezes, like moss, soil, puddles and ice sheets. They are among the most resilient of all animals, and also have some of the strangest biology.

Unlike other known animals, all bdelloid rotifers are females, with no sightings of males in the 300 years since they were discovered — rotifer mothers lay eggs that hatch into genetic copies of themselves, without sex, sperm or fertilisation.

Another surprise is that bdelloid rotifers have been stealing DNA from other organisms on a massive scale by a process called horizontal gene transfer, so that about one in ten of their genes have been copied from different kinds of life, including bacteria, fungi and even plants.

Among these stolen genes, we recently discovered that bdelloid rotifers have copied dozens of recipes for antibiotics from bacteria, which the rotifers now use to fight off their own diseases. This unusual defensive strategy could lead to short-cuts in the race to develop new drugs against antibiotic-resistant infections in human patients, and might also shed light on the strangely sexless lifestyle of these animals.

Q&A with Dr Chris Wilson

Dr Chris Wilson is a Lecturer in Biology at the University of Oxford. Originally from Kent, he completed undergraduate studies at St Anne’s College and a doctorate at Cornell University in the USA before returning to the UK, where he has held research fellowships and teaching positions at Imperial College London and St Hilda’s College, Oxford. He is interested in the causes and consequences of sexual versus asexual reproduction, which he addresses by studying the evolution, ecology and genomics of microscopic freshwater rotifers and their natural enemies, particularly pathogenic fungi.

1. If rotifers reproduce asexually, how do scientists define species?

We usually think of a species as a group of organisms that are capable of reproducing to produce fertile offspring. It turns out that even though rotifers don’t reproduce sexually, it is still possible to robustly define them into discrete species. First and foremost, this can be done based on morphology. Namely, there are consistent, clustered morphological forms which exist within the diversity of rotifers. These clustered forms are distinct from one another – it’s not just a continuous spectrum of variation. We think these discrete forms arise because the environment selects for particular shapes of rotifers’ body parts (e.g. their so-called ‘teeth’ and ‘toes’). The most suitable of these morphological forms are then preserved under natural selection. For greater precision, or as a supplement to the morphological species concept, DNA can be used. Sequencing of bdelloid rotifer DNA has corroborated that there are indeed distinct, clustered genetic sequences within the broader spectrum of variation, matching what we might generally refer to as species.

2. You mentioned rotifers stealing genes from bacteria, protists and plants. Do they also steal genes from other animals?

It’s a great question. It’s very hard to tell if rotifers have been stealing genes from other animals. In contrast, plant DNA, for example, sticks out like a sore thumb amongst the genome of a rotifer – it is clear it doesn’t belong there. Other animal DNA, if hidden amongst a rotifer’s genome, would be much less obvious. We would love to look more closely at this question. My personal guess, for what it’s worth, is that bdelloid rotifers are almost certainly stealing genes from other animals. A harder, follow-up question, would be which genes are being stolen, and what are these new genes doing?

3. How hard is it to identify rotifer species?

Generally, it is very difficult. For a start, bdelloid rotifers are soft-bodied, which means that their body parts (particularly the so-called ‘wheel organs’) are often tucked away internally and not visible. It is these body parts which are essential to view for species identification. In practice, this means you must be fast, i.e., make every effort to minimise the time taken between extracting a sample containing rotifers in the field and viewing it under the microscope in the laboratory. Preserving rotifers is an even harder job because as soon as they are disturbed they contract, hiding their characteristic features internally. The only identification key for rotifers is in German and is around 50 years old, which adds another challenge. There are only a handful of people around the world who are really good at identifying bdelloid rotifers to species level. Some of the other rotifer groups with harder bodies are more easily identified.

4. Has the process of horizontal gene transfer generally been consistent within species?

Yes, generally it has been. This is because most of the horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers occurred a very long time ago. Horizontal gene transfer in rotifers is not quick; we estimate that it tends to happen only around once every 100,000 years. Rotifers have, of course, been around for several millions of years so over this time they have nevertheless accumulated a lot of so-called ‘foreign’ genes. Indeed, horizontally gained genes make up around 10% of bdelloid rotifer genomes, i.e., 1 in 10 bdelloid rotifers genes isn’t even an animal gene! Because of how slow this process is, many bdelloid rotifer species share the same horizontal genes which arrived hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of years ago. But, simultaneously, there are handfuls of genes which are unique to particular species and therefore have arrived more recently. These clusters appear to be consistent amongst individuals within a species.

5. How exactly does horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers work?

We don’t know! One of the great problems of horizontal gene transfer in rotifers being so rare (occurring once every 100,000 years or so) is that nobody has actually witnessed it happen. Several scientists have tried to make rotifers ‘eat’ DNA to see if it is copied into their genome, but none has seemed to stick. There are various hypotheses as to how the process works. One theory is that during desiccation, the rotifers’ genome becomes damaged, and may, during the repair stage, incorporate new genes from surrounding environmental DNA. The issue with that theory is that there are bdelloid rotifers which do not survive desiccation which still have horizontal genes. An alternative hypothesis is that it’s to do with ‘jumping DNA’ – pieces of DNA which can jump from one place in the genome to another, and perhaps even transfer from one organism to another. But while lots of animals have jumping DNA, only the rotifers have gained thousands of genes horizontally. For now, it’s a mystery, but it’s a really active research area in this field, and we’d love to know the answer in the future.

Literature References

- Wilson et al. (2024) ‘Recombination in bdelloid rotifer genomes: Asexuality, transfer and stress’: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168952524000283

- Wilson and Sherman (2010) ‘Anciently asexual bdelloid rotifers escape lethal fungal parasites by drying up and blowing away’: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1179252

- Wilson et al. (2024) ‘Tiny animals use stolen genes to fight infections – and could fight antibiotic resistance too’: https://theconversation.com/tiny-animals-use-stolen-genes-to-fight-infections-and-could-fight-antibiotic-resistance-too-234737

Further Info

- Örstan and Plewka (2017) ‘An introduction to bdelloid rotifers and their study’: https://www.quekett.org/starting/microscopic-life/bdelloid-rotifers-old

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

Falling through the Cracks: iNaturalist Invertebrate Records in the UK

iNaturalist is a rapidly growing source of biological records in the UK: In 2024, over 44,000 users generated more than 1.6 million records using the platform. With the number of records generated set to increase into the future, integrating iNaturalist into UK recording systems is essential. As of 2020, iNaturalist records meeting certain criteria have been exported into iRecord, where it is hoped they will be reviewed by verifiers.

For some groups of invertebrates, however, it would appear a large proportion of iNaturalist records are not being reviewed. One explanation for this is that concerns with the data quality of records are leading verifiers to deprioritise iNaturalist as a source. All iRecord verifiers are volunteers with large workloads and limited time, so this may be justified if the data quality of iNaturalist records is indeed lower. However, this has never been quantified.

This research sought to address this, quantifying for the first time the extent of data quality concerns across taxonomic groups of UK non-marine invertebrates. Results suggest that there are indeed systemic data quality issues with iNaturalist records, though the greatest issues in reality are not always the same issues people perceive to be greatest. Many such issues will be fixable through education and outreach to iNaturalist users.

Q&A with Joss Carr

Joss Carr is an entomologist, naturalist and biological recorder who, having just finished his MSc in Biodiversity and Conservation at Queen Mary University of London and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, is now working for the Biological Recording Company as a Junior Naturalist. Joss is also a prolific user of the citizen science biodiversity platform iNaturalist. His MSc Research Project, the subject of this talk, focused on quantifying data quality concerns with biological records of invertebrates derived from iNaturalist.

How do I change my record licenses?

One of the key points I touched on in the webinar is the importance of iNaturalist users setting up their licenses in a way that permits unrestricted sharing of their observations with biodiversity data aggregators and conservation organisations in the UK. In practice, this means setting your licenses to CC-0 (public domain) or CC-BY (attribution). The default license (CC-BY-NC, an attribution non-commercial license) is not recommended, as this license greatly restricts data use. Indeed, many data users will wholesale ignore all records with this license as it would be technically illegal for them to use them. Fortunately, iNaturalist makes changing your licenses straightforward. The easiest way to do it is in the website (i.e. not the app), by going to Account Settings -> Content & Display -> Licensing, and then changing the default licenses for your observations, photos and sounds to CC-0 or CC-BY. Note that these three aspects are licensed separately. The most important one to change is your record license, but ideally change your photo and sound license too. The choice between CC-0 and CC-BY is a lot less important, instead simply reflecting whether you wish users of your data to credit you by name when they do so (CC-BY) or not (CC-0).

How do I change the name associated with my iNaturalist account?

Another key thing for iNaturalist users to do, which I stressed in my talk, is to change your display name on iNaturalist. The reason why this is important is because many users of iNaturalist data require a ‘proper’ name of the recorder to be associated with the record, primarily so they can learn to recognise and trust competent recorders. A ‘proper’ name is in the format [forename] + [surname]. Records associated with usernames or initials are far less likely to be accepted or used (although see my answer to the next question below). Changing your display name is, again, easiest within the iNaturalist website. Go to ‘Account Settings’ -> ‘Profile’ -> ‘Display Name’ and change this to your first name and surname.

What is the debate about recorder names?

A hot topic! Before the advent of photography-based biological recording, the name of the recorder responsible for the biological record was an essential part of each record because it allowed for the trustworthiness of the record to be assessed based on the known competence of that recorder. This legacy of traditional biological recording continues today; many data aggregators continue to value recorder names as crucial parts of biological records. Recently, however, some have begin to question the necessity of providing this piece of information if a unique user ID and photo are already provided. Providing one’s real name comes with privacy and security concerns, not least given individual’s records tend to be associated with sites they frequent, or even their homes and gardens. With a verifiable photo and unique user ID, and a means through which to contact the recorder, everything needed to assess the correctness of the record is arguably already provided. Necessitating the provision a recorder’s true name may not provide any supplementary value, but rather may instead put privacy-conscious recorders off from submitting records.

What happens to observations that never reach Research Grade on iNaturalist?

Short answer – almost certainly nothing. By which I mean these records are unlikely to be used to inform biodiversity science and conservation in the UK. That is unless, of course, a researcher or conservationist specifically goes to iNaturalist in search of these ‘unverified’ records. For many taxonomic groups on iNaturalist, a very large proportion of observations fall into this box; i.e. they have not made it to Research Grade. This phenomenon occurs for two main reasons: either (1) in most cases the photos provided are insufficient to confirm a species-level identification, and/or (2) there are not enough people actively reviewing and identifying incoming observations for the group on iNaturalist. This latter explanation emphasises a key call to arms – we need more taxonomic specialists on iNaturalist! If you have detailed knowledge of a group of organisms and know how to separate similar species from one another, please, contribute to iNaturalist! Your efforts will be greatly appreciated by the community.

What is being done to redress the data quality issues identified in your research?

It’s a work-in-progress area. My research represents the first time data quality concerns with iNaturalist records in the UK have been quantified. So we now have a clear demonstration of the scale of the problem. It’s now time to turn towards finding solutions. I personally believe this is primarily an awareness problem, i.e., that the main issue is that most iNaturalist users are unaware of the importance of data quality. It’s also partly going to be an effort of changing perceptions, although hopefully that should naturally follow once data quality begins to be cleaned up. I personally advocate for a dual bottom-up/top-down approach whereby simultaneously (1) iNaturalist users take responsibility for cleaning up their own data quality and spreading the word to others to do the same and (2) the organisations responsible for biodiversity data management in the UK provide assistance and guidance to support this process as much as possible. The National Biodiversity Network (NBN) have been leading this work so far within the iNaturalistUK ‘node’, and I hope to contribute to their work over the coming years through outreach campaigns and further research.

You can read Joss’ MSc Research Project final report here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CjWjprMYHAUkSsxgv9h1bu4UHXsAULJa/view?usp=sharing

Literature References

- Mesaglio (2024) ‘A Guide to iNaturalist: An Australian Perspective’: https://ala.org.au/app/uploads/2024/04/A_Guide_to_iNaturalist_Apr2024-1.pdf (N.B. the majority of the guidance here is internationally applicable)

Further Info

- iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/home

- FAQs about iNaturalist in the UK: https://nbn.org.uk/inaturalistuk/inaturalistuk-questions-answers/

- iNaturalist 2024 global stats: https://www.inaturalist.org/stats/2024

- GBIF: https://www.gbif.org/

- GBIF’s biggest species occurrence datasets: https://www.gbif.org/dataset/search?type=OCCURRENCE

- iNaturalist 2024 UK stats: https://uk.inaturalist.org/stats/2024

- iNaturalist’s place in the UK biological recording data flow: https://nbn.org.uk/inaturalistuk/inaturalistuk-and-its-place-in-biological-recording-data-flow/

- iRecord: https://irecord.org.uk/

- iNaturalist guidance on licenses: https://help.inaturalist.org/en/support/solutions/articles/151000175695-what-are-licenses-how-can-i-update-the-licenses-on-my-content-

- NBN guidance on iNaturalist licenses: https://nbn.org.uk/news/licences-on-inaturalistuk/

- National Forum for Biological Recording Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/groups/NatForumBioRecording/

- Guidance for UK iNaturalist users: https://nbn.org.uk/inaturalistuk/inaturalistuk-hints-and-tips/

- Joss’ guidance for making high quality iNaturalist observations: https://www.inaturalist.org/journal/josscarr/100039

- Parataxonomy: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parataxonomy

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk

Learn more about British wildlife

Recording Beetles at Hogsmill Valley

Blog post by Joss Carr

This article recounts the Beetle Field Recorder Day held at Hogsmill Valley on Wednesday 4th June.

Nestled along the banks of the Hogsmill River, one of London’s few chalk streams and a tributary of the Thames, are a series of interconnected nature reserves collectively known as the Hogsmill Valley. Our mission: Survey these reserves for beetles. It was an ambitious plan, with four sites to hit over the course of the day. We would start in the south, at Six Acre Meadow, and work our way north, ending at Rose Walk. 16 naturalists rallied for the task, representing a range of experiences from beginner to dedicated enthusiast. The party was helmed by beetle specialist Wil Heeney. Equipped with sweep nets, trays, pots and cameras, we set out.

Site 1: Six Acre Meadow

The day immediately got off to a strong start at our first site: Six Acre Meadow. The dense, lush grass of the meadow was alive with insects on our visit, including plenty of beetles. Sweep netting quickly yielded several soldier beetles (family: Cantharidae), including Cantharis fusca, C. lateralis and C. figurata, as well as the common Malachite Beetle (Malachius bipustulatus) and its slightly less well-known cousin Cordylepherus viridis. The distinctive, shining green Swollen-thighed Beetle, Oedemera nobilis, was also found. By far the most abundant beetle, however, was the grey-green Oedemera lurida, which close to every single participant managed to find within a few minutes.

As can be expected in any meadow, ladybirds (family: Coccinellidae) were also abundant, with the 24-spot Ladybird (Subcoccinella vigintiquattuorpunctata) particularly prolific. 7-spot Ladybird (Coccinella septempunctata), 2-spot Ladybird (Adalia bipunctata) and mating 22-spot Ladybird (Psyllobora vigintiduopunctata) were also found.

The meadow also proved very good for weevils. The bulky and prickly Sciaphilus asperatus, the neat black Rhinoncus perpendicularis and the extravagantly patterned Nanophyes marmoratum were all found from sweeping the grass. Zacladus exiguus was swept from a large patch of Cut-leaved Crane’sbill (Geranium dissectum) on the meadow edge, upon which it feeds.

In terms of smaller beetles, two nice flea beetle species were found from sweeping: the yellow Aphthona lutescens and the pitch-black Chaetocnema concinna. Flea beetles are a tribe (Alticini) within the family Chrysomelidae (the ‘leaf beetles’) which are distinctive for their greatly enlarged hind femorae (essentially their ‘thighs’) which are adapted for jumping; hence ‘flea beetle’ (see photos below). Though very common, they are a challenging group to identify as most are very small (<5 mm) and often require dissection to identify.

Ironically, likely the best find from our visit to Six Acre Meadow in terms of rarity was not a beetle but two leafhoppers (family: Cicadellidae). What immediately caught the eyes of a few participants upon arriving in the meadow was a large patch of Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria). Sweeping this yielded two leafhopper species which are found only on Meadowsweet as a host plant: the small and spotted Eupteryx signatipennis and the larger Macrosteles septemnotatus. Due to their strict requirements for large patches of their host plant, both these hoppers are rarely recorded. As per the NBN Atlas, the day’s records represent the first ever London record for E. signatipennis and the second ever for M. septemnotatus.

With our ambitious schedule for the day, it was soon due time to depart Six Acre Meadow and head onwards. In the ever-distracted fashion of naturalists, however, a shout from one participant standing in a bramble bush quickly brought everyone over. She had noticed several jewel beetles (family: Buprestidae) flying between the bramble flowers. Most infamous for being wood-boring pests of timber plantations, jewel beetles are also – as the name suggests – stunningly beautiful beetles that, with their metallic and iridescent colouring, resemble jewels. The jewel beetle found on the brambles was a gorgeous metallic green one: Agrilus angustulus.

Site 2: Southwood Open Space

Despite being little more than 300 metres north of Six Acre Meadow, our second site – Southwood Open Space – was distinctly different in character. Where Six Acre Meadow had been lush and green, Southwood Open Space, like many parks around London this summer, was very dry. The vegetation character of the meadow was also notably different. Where tufts of Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) and Meadow Crane’s-bill (Geranium pratense) had dotted Six Acre Meadow, Southwood Open Space’s most notable plant was the surprisingly abundant Wild Onion Allium vineale.

The beetles found, however, were more or less the same. Among the larger beetles, novelties from the grassland itself were limited to the fourth soldier beetle species of the day in Cantharis decipiens, the 14-spot Ladybird Propylea quattuordecimpunctata and the green weevil Phyllobius roboretanus.

Perhaps the most interesting beetle find at this site was the co-occurrence of three species of very similar Protapion weevils swept from a large patch of White Clover (Trifolium repens). The Protapion weevils are a tricky bunch, with 10 British species all found on clovers and all black with orange legs. To distinguish them is usually a microscopy job, looking at details of the different segments of the legs as well as the shape of the rostrum (the weevil’s ‘nose’).

Likely the ‘rarest’ find at this site was Phalacrus corruscus, a tiny (2mm long) shiny black beetle and a member of the family Phalacridae (the ‘Shining Flower Beetles’), a family of beetles which are often found in sweep net samples. Many refrain from collecting these species given the high-power microscopy needed to identify them through examining details of the legs and elytra, however when one does succeed in doing so you are often met with a relatively ‘rare’ find (in the sense of an infrequently recorded species). The day’s record was the fifth ever for London.

Besides the meadow itself, a brief shake-down of an English Oak (Quercus robur) and Hybrid Crack Willow (Salix × fragilis) on the edge of the field yielded a few nice species including the leafhopper Alebra albostriella and the plant bug Phylus melanocephalus from the former, as well as the ever-present Willow Flea Beetle Crepidodera aurata from the latter.

Site 3: Elmbridge Meadows

Hugging the Hogsmill River for just shy of a kilometre, Elmbridge Meadows – our next site – acts as a crucial ‘green corridor’ in the borough. What it lacks in width it makes up for in interesting habitat. The Hogsmill is lined here with gorgeous old willows (Salix spp.) and poplars (Populus spp.), and a diverse sward of shrubs line the footpath as it snakes north. It was here that many of the days’ most exciting finds were made.

The first of these excitements was a moth! And if your natural reaction to that is to question why a moth deserves mention in a blog about beetles (fair enough), that is because this was not just any old moth, but rather a Hornet Moth (Sesia apiformis). Without much question at all this is one of the most charismatic and attractive of all the British Lepidoptera, and quite rare too. The Hornet Moth is a clearwing moth, part of the family Sesiidae which features 16 UK species which are at most uncommon and several of which are stupidly scarce. Without concerted search effort using pheromone lures, the average naturalist in the UK can expect to see only a handful of these gorgeous moths in a lifetime.

As you might guess from the name, Hornet Moths are Batesian mimics of Hornets (Vespa crabro). In flight or from a distance you could quite easily be fooled, especially because they are a similar size. Adult Hornet Moths are generally only ever found on or near poplars (Populus spp.) – the larvae feed on the wood pulp at the base – and almost exclusively in June. That is to says the conditions we saw ours were exactly right. Check out this beauty!

Back to beetles now, and the theme of mimicking black-and-yellow buzzing things nevertheless continued. Sweeping of Hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) umbellifers alongside the riverbanks yielded another gorgeous insect: the Wasp Beetle (Clytus arietus). This is another species which is not often seen given it is reliant on good quality deadwood habitat. In this case it mimics wasps in the genus Vespula (i.e. the Common and German Wasp).

Other beetle highlights from Elmbridge Meadows included:

- Two common leaf beetles (family: Chrysomelidae): Gastrophysa viridula found on dock (Rumex sp.) and Plagiodera versicolora found beneath willow (Salix sp.).

- The first ground beetle (family: Carabidae) of the day: the common Harpalus affinis, found running across the footpath

- The fifth soldier beetle (family: Cantharidae) of the day, Cantharis pellucida, found on a bramble thicket

- The metallic blue flea beetle Altica lythri, swept from vegetation along the riverbank and dissected under the microscope for identification

- The long-nosed weevil Ceutorhynchus obstrictus

- A nice selection of host-specific apionid weevils swept from Common Mallow (Malva sylvestris): Aspidapion aeneum, Aspidapion radiolus, Malvapion malvae and Pseudapion rufirostre

The only other thing of note in Elmbridge Meadows on our visit was the remarkably large numbers of Harlequin Ladybirds (Harmonia axyridis). Close to every single leaf of the bramble thicket which lined each side of the footpath had either a larva, adult or cluster of eggs on it. It seems to have been a very productive year for the species.

After a quick lunch where we delighted in watching damselflies dance over the river, we headed out of Elmbridge Meadows and towards the last site for the day: Rose Walk.

Site 4: Rose Walk

By this point – having been out and about for nearing 5 hours – fatigue was beginning to set in, and so recording levels dropped a little such that only the most interesting specimens garnered attention. Fortunately, a few last-minute beetle delights were nevertheless offered up by Rose Walk. Fittingly, the first of these was a Rose Chafer (Cetonia aurata), with its gorgeous iridescent green elytra shining in the afternoon sun. The chafer beetles, of which Cetonia aurata is the most common and well-known, represent several subfamilies within the family Scarabaeidae. They are a nice group of beetles to get to know as a beginner as all the species are large and relatively easy to tell apart once learnt. For those interested, Wil Heeney – who led the Field Recorder Day – is running a training webinar about these beetles, including the Rose Chafer, on the 15th of September. Sign up here!

Given how dry this summer has been in southern England, deadwood has fallen off most naturalists’ radars. Nevertheless, a particularly promising log was noticed right towards the end of the day and, as if to see us off, yielded one of the largest and most loved of the British beetles: the Lesser Stag Beetle (Dorcus parallelipipedus).

All in all, the Field Recorder Day was a resounding success, with 16 participants generating 137 records of 89 species in total, including 64 records of 42 beetle species. Records were spread across the four sites as follows:

- Six Acre Meadow: 43 records of 41 species (including 22 records of 22 beetle species)

- Southwood Open Space: 39 records of 30 species (including 22 records of 16 beetle species)

- Elmbridge Meadows: 42 records of 34 species (including 16 records of 13 beetle species)

- Rose Walk: 11 records of 9 species (including 6 records of 4 beetle species)

Thanks very much to everyone who attended and recorded beetles and other interesting species. It was a very fun day and we hope to see people again at similar future events, which you can sign up for here.