Rivers in the UK are facing an unprecedented threat from human disturbance but it can be challenging to identify the pollutants that are driving biodiversity loss in a particular location through traditional water testing methods. However, the invertebrates living in our waterways are particularly sensitive to pollution and the impacts can clearly be seen in their populations long after any particular incident. SmartRivers is a pioneering programme run by WildFish that builds on the work of The Riverfly Census using surveys of freshwater invertebrate populations to identify the challenges facing freshwater systems.

This project enables community groups, trusts, and other organisations to benchmark and monitor the health of their own rivers. The evidence collected by the SmartRivers programme allows for both local and national engagement on a range of issues to better protect our valuable freshwater habitats. Dr Sam Green gives an overview of the methods used to monitor freshwater invertebrate populations, the work we do, and how you can get involved. He will also discuss the power of citizen science in addressing gaps in government monitoring efforts and highlight some case studies demonstrating the importance of data collected from WildFish’s SmartRivers programme.

Q&A with Dr Sam Green

Dr Sam Green is a freshwater ecologist at WildFish primarily supporting SmartRivers. WildFish is the only independent charity in the UK campaigning for wild fish and their habitats. We identify and lobby against the key threats driving the decline in wild fish populations, from various forms of pollution to open-net salmon farming. Ultimately, our goal is for fresh and coastal water habitats that are clean, healthy, biodiverse, and able to support sustainable populations of wild fish.

- What percentage of UK rivers are being monitored using the SmartRivers methodology?

This is variable by year as it depends on the funding of individual hubs. In a given year, some hubs will cease and some will expand their programme. The short answer is probably not enough! - How long does it take to process one sample?

Again, this is variable depending on what is in the river, if the group undertake their sampling as a single group versus pairs and the method by which the specimens are being identified. To do the kick sampling is just 3 minutes plus 1 minute of hand-searching so the time spent in the river is relatively low. Depending on how many sites a hub monitors, they can generally do their sampling in a day. The time-heavy component is the identification – if you are in a perfect chalk stream habitat you could be collecting thousands of mayflies. for those hubs that do the ID in-house, they tend to get together as a group and usually take a full day to get through the sample for a single site. - Do you have quality assurance procedures in place to verify the species identifications?

Quite a lot of our hubs do opt for the ‘sample and send’ due to the time commitment that is required for ID and because they have funding to do so. These specimens would be identified by a professional entomologist. For the hubs that undertake all of the identification themselves, one in five samples are randomly selected for quality control. These are sent to a professional entomologist and we then organise a follow-up meeting with the hub to go over any discrepancies and provide guidance for the group. - Do you use the data from the Riverfly Monitoring Initiative data in your analysis?

The two schemes complement each other in terms of monitoring rivers, but ARMI data and SmartRivers data do different things. The acute issues monthly bankside monitoring sampling is designed to pick up pollution events and uses family-level identification. SmartRivers uses species-level identification with monthly monitoring and twice-annually deep dives into the chronic pressures on rivers. - Is SmartRivers able to detect impacts from pet flea treatments?

Although I’ve focused on sewage release in this talk, SmartRivers can detect other pressures and pet flea treatments are one that we’ve been discussing a lot recently. There are pet flea treatments that you can buy on Amazon that contain neonicotinoids that are banned for agricultural use, and the impact on rivers is amplified when this is a ‘spot-on’ treatment rather than a tablet. this will get picked up in our chemical stress score. To use a hypothetical, if you were monitoring a stretch of river that you care about and you know there is an area where lots of dogs are entering the water, you could monitor sites upstream and downstream of this to identify any impact. Up to 90% of chemicals entering our waterways are from medicine – human and veterinary. - Is the SmartRivers data publicly available?

Yes, via Cartographer – though there is obviously a lag as we process data and add it each year. Instructions for accessing this can be viewed in the video below.

Literature references

- Haase et al (2023) The recovery of European freshwater biodiversity has come to a halt: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06400-1

- Salmon and Trout Conservation (2016) Riverfly Census 2015: https://wildfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2015-Report_Riverfly-Census.pdf

- Salmon and Trout Conservation (2019) Riverfly Census 2019: National Outcomes and Policy Recommendations: https://wildfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Riverfly-Census-National-Outcomes-2015-1.pdf

- WildFish (2023) SmartRivers: Our Progess to Date: https://wildfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/SmartRivers-Progress-Update-2023.pdf

- WildFish (2023) SmartRivers: What your data told us in 2022: https://wildfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2022-SmartRivers-data-update_271123.pdf

- WildFish (2021) Riverfly Census Revisited: A National Emergency: https://wildfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2021-Riverfly-Census_200722.pdf

Further info

- WildFish website: https://wildfish.org/

- SmartRivers webpage: https://wildfish.org/project/smart-rivers/

- Riverfly Census webpage: https://wildfish.org/project/smart-rivers/

- Freshwater invertebrate ID guides from the FSC: https://www.field-studies-council.org/product-category/publications/?fwp_natural_history_courses=freshwater-invertebrates

- Freshwater ecology training courses from the FSC: https://www.field-studies-council.org/courses-and-experiences/subjects/freshwater-ecology-courses/

- Aquatic Insects Special Interest Group from the RES: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/membership-and-community/special-interest-groups/aquatic-insects/

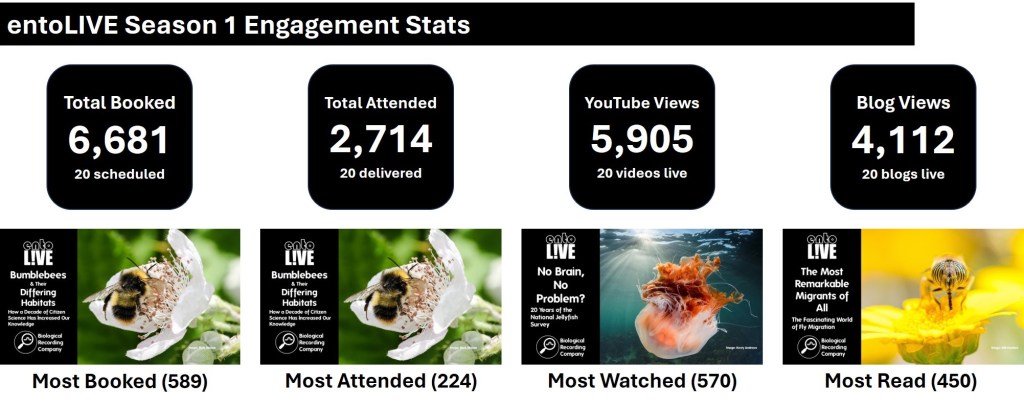

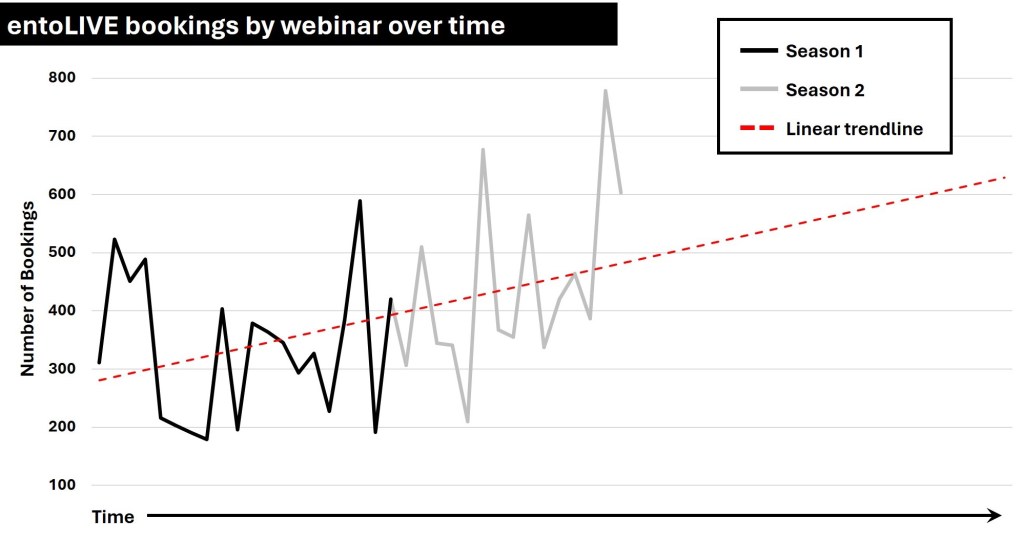

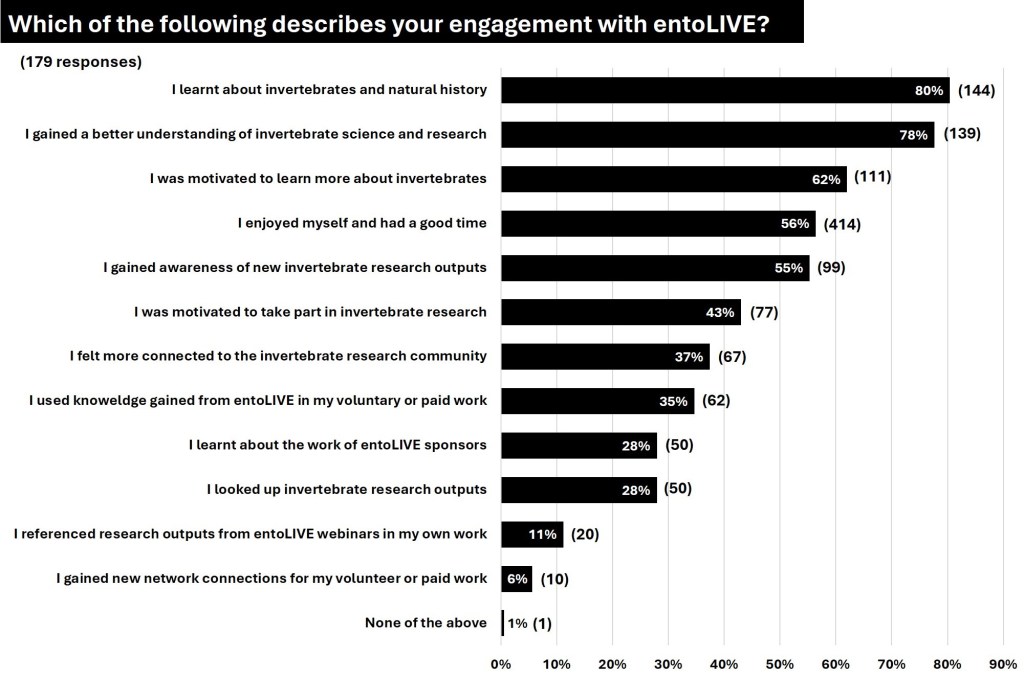

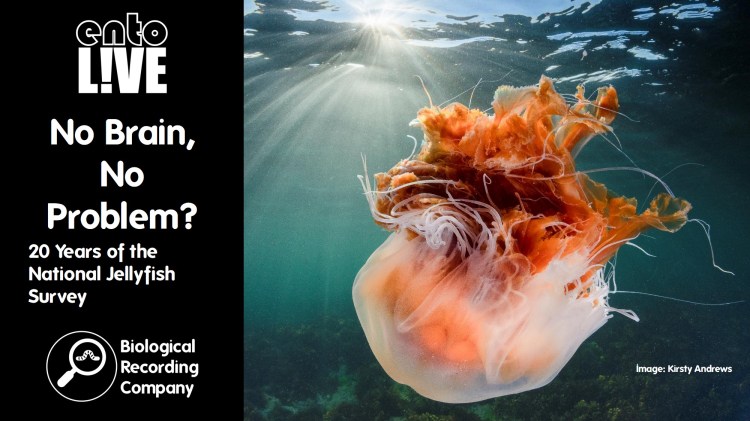

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is only possible due to contributions from our partners.

- Find out about more about the British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk/

- Browse the list of identification guides and other publications from the Field Studies Council: https://www.field-studies-council.org/shop/

- Check out environmentjob.co.uk for the latest jobs, volunteering opportunities, courses and events: https://www.environmentjob.co.uk/

- Check out the Royal Entomological Society‘s NEW £15 Associate Membership: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/shop/membership-and-fellowship/associate-member/