Farmland biodiversity is thought to be steeply declining throughout Europe, and society at large is increasingly concerned about the loss of public goods, such as iconic wildlife and cultural landscapes, yet to date few studies have been able to produce data to support or refute this claim. During this presentation, Stuart will showcase previous work establishing relationships between butterfly recorders and farmers, and how participating in monitoring on farmland influenced perceptions of biodiversity and biodiversity-friendly farming practices whilst providing valuable recorders to the record pool. Stuart will then discuss future plans to increase the scalability and capacity of this model to wider communities and taxa.

Dr Stuart Edwards is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Reading with an interest in agroecology, citizen science and sustainable farming.

Q&A with Dr Stuart Edwards

- How do you recruit participants for the project?

We piggybacked on the local Butterfly Conservation groups. Each county has a regional coordinator, and these were able to send out details for getting involved to their mailing lists. This is a challenge that we’ll need to consider for other species groups, particularly ones that don’t have regional networks. - What were the motivations for participants getting involved?

We had some recorders who really enjoyed just being out and about on farmland, and their regular walks had evolved into ad hoc recording and then on to monitoring. Some of the sites were in really beautiful parts of the country and getting involved in this project enabled people to volunteer in these wonderful habitats. - Were your records shared with other organisations?

Our survey data was submitted to the UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme website, so it will form part of the national datasets and this is also shared through County Recorders with the network of Local Environmental Record Centres. The surveys differed slightly from the UK Wider Countryside Butterfly Survey in that our transects were not in randomised squares, but at sites that we were selecting for monitoring. - Are there any plans for expanding the project?

The workshops that I’m looking to run will investigate what biodiversity data farmers want and need to make decisions for considering and improving biodiversity on their land. The results of this will impact the direction we would look to take, for example, which national citizen science programmes we could tap into to facilitate that data collection. This in turn may impact where it would be feasible to undertake the project geographically. - Why is the survey undertaken just twice per year?

Undertaking the survey twice per year does have limitations as it just gives us a snapshot of the species at the time of the survey, in contrast to the UK BMS which is a weekly survey over a set period. We opted to go for 2 surveys to balance the data requirements of the project with the amount of commitment we are asking for from our volunteers. If we asked for more surveys, this would have likely resulted in fewer surveyors.

Literature references

- Kleijn et al (2023) Ending the curve of biodiversity loss requires rewarding farmers economically for conservation management: https://showcase-project.eu/storage/app/uploads/public/63b/d0a/8f2/63bd0a8f240c2479631112.pdf

- Ruck et al (2023) Farmland biodiversity monitoring through citizen science: A review of existing approaches and future opportunities: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13280-023-01929-x

Further info

- Showcase Project: https://showcase-project.eu/

- Showcase ‘Spiders, Earthworms and Beetles: The Impacts of Cover Crop Frost Tolerance‘ entoLIVE webinar: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/734806966417

- British Butterfly Wild ID Guide from the Field Studies Council: https://www.field-studies-council.org/shop/publications/butterflies-guide/

- UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme: https://ukbms.org/

- Wider Countryside Butterfly Survey: https://butterfly-conservation.org/our-work/recording-and-monitoring/wider-countryside-butterfly-survey

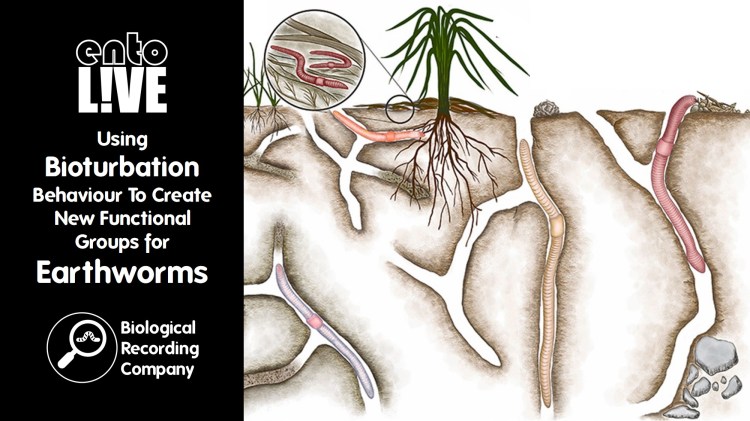

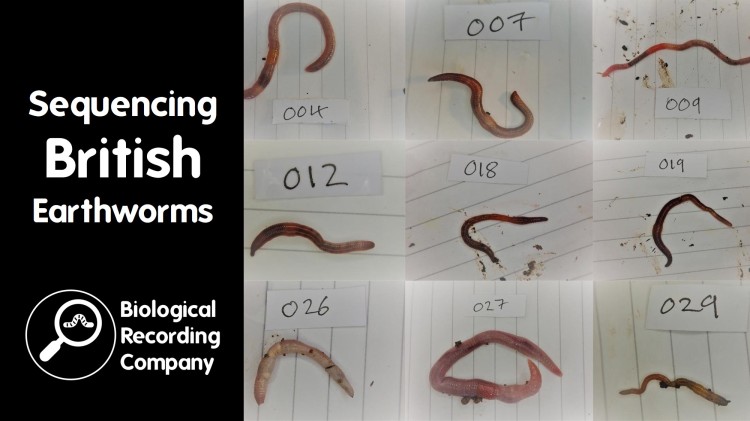

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk