Greater Lincolnshire Nature Partnership works with 49 Partners across Greater Lincolnshire to achieve more for nature. The nature partnership also hosts the Local Environmental Records Centre. This close working relationship has allowed for multiple projects, which are highlighted in this presentation.

Charlotte Phillips is the manager of the Greater Lincolnshire Nature Partnership, including the Local Environmental Record Centre. Charlotte is also a Director of ALERC and Trustee of The Wallacea Trust. With a background in both national and international conservation, Charlotte believes strongly in partnerships working across sectors to achieve current environmental goals.

Q&A with Charlotte Phillips

- Is it worth collecting records for Local Environmental Record Centres when some ecological consultants may not use them?

LERCs use data for a wide range of services and data searches for planning are just one of those services – so yes, please do submit your records to your LERC to ensure that it is getting used. The importance of local data has been highlighted through the Local Nature Recovery Strategies. Secondly, it is best practice for data searches that form part of planning applications to include data searches performed by the relevant Local Environmental Record Centre(s). Ecological consultants are using our data in our county and this is increasing each year. - What factors are you using to identify and prioritise opportunities for biodiversity mapping?

My colleague designed a model that had over 1,000 different questions/rules behind it, but the biggest thing was linking the areas that are already in a good state for nature (such as Local Wildlife Sites, Local Nature Reserves etc.). Connectivity is really important for us. We’ve excluded grade 1 and grade 2 agricultural land as this is great for farming and the chances of it being taken out of agricultural use for nature recovery is almost zero. - Are local geological sites included within Local Nature Recovery Strategies?

This will vary by area and depend on the individual Local Nature Partnership and if this is something they are considering. We have 2 steps in mapping for the LocalNature Recovery Strategy. The first step is very prescriptive to ensure all regions are mapping things in the same way – giving us comparable baseline maps. This map will just include local wildlife sites and not local geodiversity sites. The second step is to add sites that are important for (or could become important for) biodiversity. This step is very much locally driven, so if there is an argument that geodiversity sites need to be considered it would be during this step. It’s also worth noting that a site may be both a local wildlife site and a local geodiversity site – in which case it would be included in step 1 anyway. - Are you able to give us an idea of how much designing the LERC search cost?

The tool was developed in 2017 and cost GNLP around £30,000 at the time. Our developer gave us a good deal in the hope that more partners would come on the journey, but this didn’t happen. We have just put in another £20,000 recently to upgrade the tool and add the search area function. - Are there any improvements that you would make to your county’s nature partnership?

More funding would always be welcome – we could do more with more staff! We have reached the limit of what we can do with the capacity that we have. Our partners are really supportive, and we’d love to get involved with more of the projects that they invite us to get involved with. - How do you ensure that partners are not just signing up for greenwashing purposes?

This is something that we are aware needs careful attention. We’re taking our time with this to ensure that we get things right. We’ll most likely stick with our current partners and introduce a system for supporters to get involved. Supporters won’t have voting rights on what we do and would still need to be in line with the ethos of the partnership – for example aligning with our position statements on things like tree planting and climate.

Further info and links

- Greater Lincolnshire Nature Partnership: www.glnp.org.uk

- Greater Lincolnshire Environmental Records Centre: https://search.glnp.org.uk

- Greater Lincolnshire Local Nature Recovery Strategy: www.glincslnrs.org.uk

- Greater Lincolnshire LNRS Linktree: https://linktr.ee/glincslnrs?utm_source=qr_code

- FREE Local Nature Recovery Strategies: Update and Challenges virtual event: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/777642027237

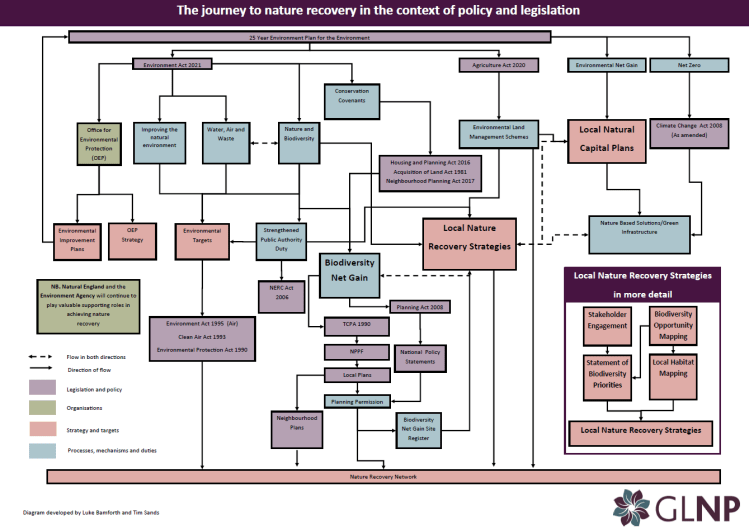

- GNLP ‘Journey to Nature Recovery’ diagram