Cover crops are used in arable rotations to protect the soil between cash crops (e.g. wheat, barley). Cover crops need to be removed before cash crops can be planted, and this is commonly done by spraying environmentally-harmful herbicides. Here, we conducted a large-scale field trial to test whether using cover crops that die naturally in the frost is better for earthworms, spiders, and beetles, and associated ecosystem functions (e.g. soil compaction). The aim is to design and test the ecological benefits of cover crop mixes that can be removed with minimal herbicide use. This experiment was co-designed with 15 farmers, LEAF, and Oakbank.

Dr Amelia (Millie) Hood is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Reading. She’s interested in co-designing sustainable farming solutions with farmers in the UK, and using large ecological experiments to test them.

Q&A Dr Amelia Hood

- Did you use existing survey methods for the groups that you monitored?

The methods used were not new, scientists have previously used quadrants to study plants, vortices to study beetles and spiders and soil monoliths to study earthworms. The Showcase project designed protocols using these sampling methods that were used to ensure that the way the sampling was done was consistent across all of the sampling within the Showcase project. For example, with vortice sampling this means standardising factors such as number of seconds the vortice is used, the size of the area sampled and the distance between sample points. - Do you know what percentage of farms are already using cover crops?

This is information that would be really valuable but, unfortunately, I don’t have access to this information. This would be a great project. A possible way of doing this would be to collaborate with the major cover crop suppliers and see which are their most popular mixes. You’d also need to consider the motivations behind the use of cover crops, as farmers have different motivations (including for pollination, reducing nitrate leaching or improving soil structure) and this would impact which mixes they would look to use. - Are there alternatives to using chemicals to remove the cover crop?

There are two main ways to kill off the cover rop. The first is use of herbicides. The amount of spraying can be reduced by grazing, rolling off or planting winter sensitive species. The second option is manual removal, which would be the method used by organic farms. There are disadvantages to both of these methods. Herbicides result in chemical run-off and contamination. Manual removal through tilling will lead to increased soil compaction. There is a lot of debate in the scientific and farming communities about which methods are less destructive for the environment and there is no easy answer. I’ve noticed that farmers that I’ve worked with seem to be getting more responsive, and are thinking more about interventions, for example tilling only when they feel it is needed rather than tilling at a set frequency each year. - Did the farmers get paid for taking part in this research?

No, participation in this research was voluntary and we are extremely grateful for the farmers that allowed us to undertake this research on their land! - What is the next step in this research?

Continuity is a really big issue in the world of research. Research grants are usually 3-5 years and arable rotations can be as long as 8 years. Some funding bodies do support long-term experiments, particularly as the value of these is recognised with long-term experiments contributing disproportionately to policy and practice. It can sometimes be tricky to get repeat funding for continuing or extending a project, as there can be an emphasis on supporting new and snazzy projects. I will be continuing working on co-design with farmers and will be looking at agroforestry where you plant rows of trees in arable fields.

Literature References

- Brennan (2014) A Comparison of Drill and Broadcast Methods for Establishing Cover Crops on Beds: https://journals.ashs.org/hortsci/view/journals/hortsci/49/4/article-p441.xml

- Klebl et al (2024) How values and perceptions shape farmers’ biodiversity management: Insights from ten European countries: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320724000570?via%3Dihub

- Michalko et al (2018) Habitat niches suggest that non-crop habitat types differ in quality as source habitats for Central European agrobiont spiders: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167880920304345

- Nivelle et al (2016) Functional response of soil microbial communities to tillage, cover crops and nitrogen fertilisation: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0929139316302190?via%3Dihub

- Shackelford et al (2019) Effects of cover crops on multiple ecosystem services: Ten meta-analyses of data from arable farmland in California and the Mediterranean: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837718312584

- The Royal Society (2020) Soil structure and its benefits: An evidence synthesis: https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/soil-structures/soil-structure-evidence-synthesis-report.pdf

Further Info

- Linking Environment And Farming (LEAF): https://leaf.eco/

- Showcase Project: https://showcase-project.eu/

- Showcase Butterflies entoLIVE: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/2024/01/22/showcase-butterflies/

- Six Inches of Soil documentary: https://www.sixinchesofsoil.org/

- UK Beetle Recording: https://www.coleoptera.org.uk/

- Earthworm Society of Britain: https://www.earthwormsoc.org.uk/

- Earthworm crowned UK invertebrate of the year by Guardian readers: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/apr/15/earthworm-crowned-uk-invertebrate-of-the-year-by-guardian-readers#:~:text=The%20 common%20 earthworm%2C%20the%20 soil,invertebrate%20of%20the%20year%20competition.

- Cotswold Seeds: https://www.cotswoldseeds.com/

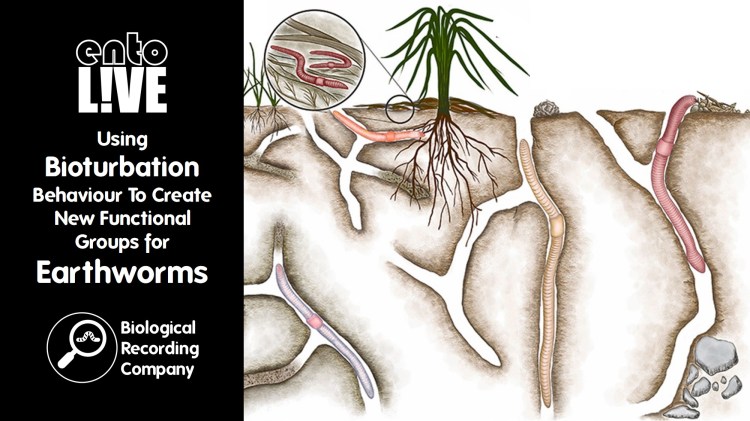

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk