Ant foragers are champion navigators capable of accurately repeating long journeys through complex cluttered terrain. While social cues, such as chemical trails, can help navigation in some species. Most ants are capable of individual navigation, where each forager has a remarkable sense of direction, allied to sophisticated landmark learning, such that they can navigate huge distances between their nest and foraging areas.

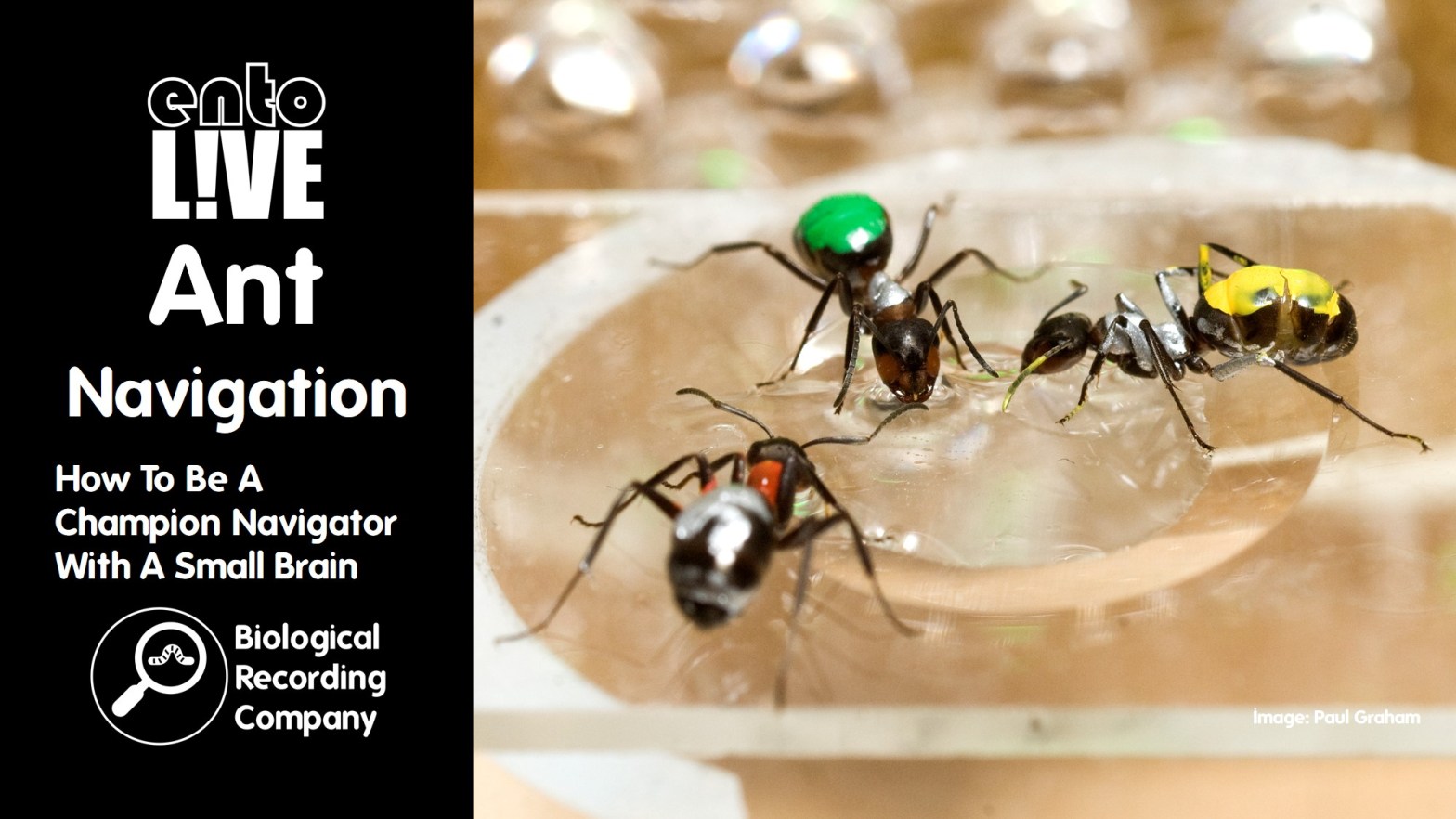

Q&A with Prof Paul Graham

Prof Paul Graham first became interested in Artificial Intelligence during a Psychology degree, specifically the prospect of capturing aspects of biological intelligence by mimicking insects. This led to a PhD at Sussex with Prof Tom Collett, where he studied spatial cognition in ants with the hope of understanding enough about ants to be able to build ant-inspired robots. 25 years later and he’s still studying ants and realising there is a lot to know before we can hope to build a robot half as smart as an ant. His ongoing research is interested in how neural and sensory mechanisms are tuned to an animal’s natural environment to produce their remarkable foraging behaviours.

- Do ants have ocelli to sense light like bees?

Some ants do, for example, the desert ants in these studies do. We don’t know for certain why these are needed as they perform similar functions to the compound eyes in ants. It’s always good to have a backup, so the information gathered via ocelli may be improving how robust the navigation system of an ant is by acting as a backup to the information gathered through the compound eye. For instance, if you cover up the compound eyes, ants can still do an approximate form of path integration (though it is much less accurate). It could be that these are a vestigial feature, or that they are still used by male ants when they fly during dispersal points in the life cycle. - Does the Earth’s magnetic field play a role in ant navigation?

There is really exciting research (From Wurzberg) into how magnetic fields are used during learning walks. The sun is a better compass than the magnetic field, but an ant can’t know in advance where their nest is going to be so they need to learn about the movement of the sun for their particular location on the planet and also for the time of year when an ant becomes a forager. In the early stages of becoming a forager, ants use the magnetic field as a scaffold to try and learn how the sun moves throughout the day. So the magnetic field is important initially and is subsumed by sun compass information later. - Do ants use social cues, like the waggle dance in honeybees, to communicate to other members of the colony where fto go and forage?

It is much less sophisticated than in honeybees. Ants will give social cues to go out and forage (such as sharing smells or actual food). This is more of a nudge to go out and forage, rather than giving information about which direction or location to visit. - If we are no better at navigation than a hamster or an ant, does this imply that, in evolutionary terms, a navigation system was optimised very early on and has not been improved much since?

It’s important to remember that there are different types of navigation behaviour. Humans have other navigation abilities at their disposal – we can build large volumes of navigation memories and we’re good at linking other memories to places (using actions, events and emotions to a location). Path integration was probably optimised long ago, and we see it regressing and improving again in species over time according to their evolutionary needs. - How does light pollution impact ant navigation?

Even nocturnal ants tend to be crepuscular, meaning they tend to need a bit of light and do most of the navigating at dawn or dusk and possibly some local foraging when it is dark. Light pollution is likely to increase the amount of time that these ants can navigate. We don’t know what the actual impact of this is though – it could benefit them as they get more foraging time or it could disadvantage them against their predators.

Literature references

- Buehlmann, Graham, Hansson & Knaden (2014). Desert ants locate food by combining high sensitivity to food odors with extensive crosswind runs: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.056

- Buehlmann, Mangan & Graham (2020). Multimodal interactions in insect navigation: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10071-020-01383-2

- Durier, Graham & Collett (2003). Snapshot memories and landmark guidance in wood ants: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-08639-002

- Graham & Cheng (2009). Ants use the panoramic skyline as a visual cue during navigation: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982209015851

- Collet & Zeil (2018). Insect learning flights and walks: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.050

- Dacke et al (2013) Dung beetles use the Milky Way for orientation: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.12.034

- Jékely et al (2008) Mechanism of phototaxis in marine zooplankton: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19020621/

- Kohler & Wehner (2005). Idiosyncratic route-based memories in desert ants, Melophorus bagoti: how do they interact with path-integration vectors?: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15607683/

- Santschi, F. (1913). Genre nouveau et espèce nouvelle de Formicide [Hym.]. Bulletin de la Société entomologique de France, 18(19), 478-478.

- Souman et al (2009) Walking straight into circles: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19699093/

- Stieb et al (2011) Antennal-lobe organization in desert ants of the genus Cataglyphis: https://doi.org/10.1159/000326211

- Santschi, F. (1913). Genre nouveau et espèce nouvelle de Formicide [Hym.]. Bulletin de la Société entomologique de France, 18(19), 478-478.

- Tinbergen & Tinbergen (1974) The Animal in Its World (Explorations of an Ethologist, 1932-1972), Volume Two: Laboratory Experiments and General Papers (Vol. 2). Harvard University Press.

- Wehner (2003) Desert ant navigation: how miniature brains solve complex tasks: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12879352/

- Wehner et al (2004) The ontogeny of forage behaviour in desert ants, Cataglyphis bicolor: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0307-6946.2004.00591.x

- Wehner (2020) Desert navigator: the journey of an ant. Harvard University Press

- Wittlinger et al (2006) The ant odometer: stepping on stilts and stumps: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1126912

Further info

- A Crap Talk About Orientation – Dung Beetles TEDx talk by Maria Dacke”: https://youtu.be/ETtEdsdkOzE

- BBC Silver Desert Ant video: https://youtu.be/mCaVvHeI8jU

- Neural Mechanisms of Insect Navigation lecture by Barbara Webb (Stanford University) video: https://youtu.be/KpaPakvEGkY

- Behaviour Special Interest Group with RES: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/membership-and-community/special-interest-groups/behaviour/

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is only possible due to contributions from our partners.

- Find out about more about the British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk/

- Browse the list of identification guides and other publications from the Field Studies Council: https://www.field-studies-council.org/shop/

- Check out environmentjob.co.uk for the latest jobs, volunteering opportunities, courses and events: https://www.environmentjob.co.uk/

- Check out the Royal Entomological Society‘s NEW £15 Associate Membership: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/shop/membership-and-fellowship/associate-member/