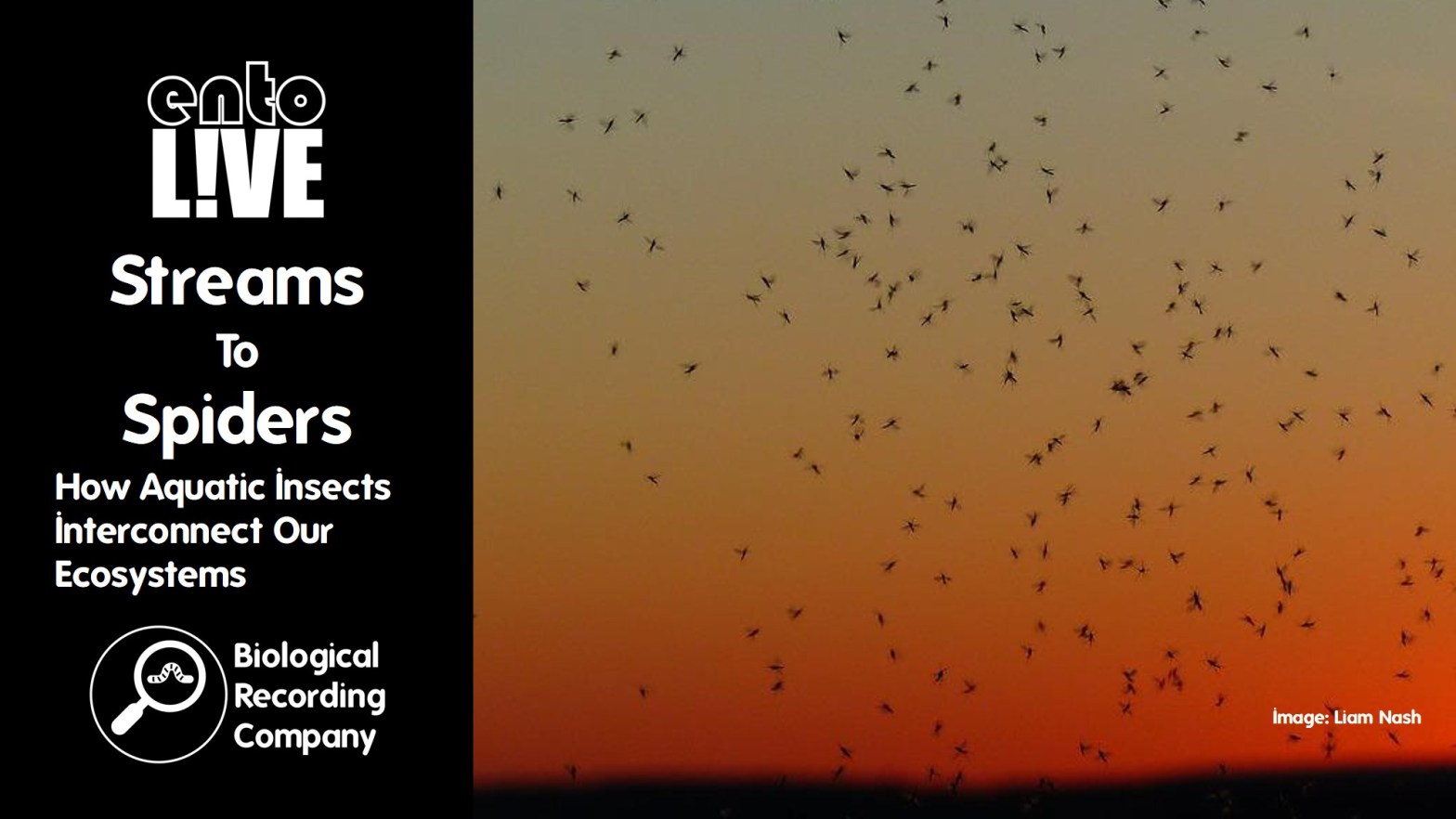

Freshwaters and forests might seem like definitively separate habitats, but they are in fact tightly interconnected by insects. These insects, such as mayflies, dragonflies and mosquitoes, develop in water but emerge onto land as winged adults, with a powerful impact on the surrounding landscape. Some feed birds, bats, lizards and spiders, others transfer microplastics and heavy metals out of rivers and others form swarms so large they are picked up by weather satellites. This talk delves into how these largely overlooked insects create an interconnected world in ways we don’t always expect.

Q&A with Liam Nash

Liam Nash is a 4th-year NERC PhD student primarily based at Queen Mary, University of London in collaboration with ZSL and the University of Campinas. He specialises in community and conservation ecology and has worked with all kinds of invertebrates in Brazil and across the UK.

- Late and reduced emergences of mayflies have been observed in my area (northeast Wales) but caddisflies attracted to my light trap don’t show the same. Have you suggestions about why this might be?

My research has looked at things from a broad perspective and looking at overall patterns, rather than focusing on individual species or groups. There could be a wide range of triggers that are impacting emergence times, and these will vary between groups (such as mayflies and caddisflies) and even between species. If we take changing climate as an example, and the impacts that this has on temperature – this could impact different species depending on the specific trigger for emergence for a given species. In some species, emergence may be triggered by the winter temperature, while others may be triggered by the spring temperature. In others still, it could be that reaching a specific temperature is a trigger or a sustained period above a temperature. Climate change affects each of these temperature variables in different ways. So, in summary, the only way to answer your question with confidence would be to study the species (or species groups) present in that area to better understand the triggers for emergence and how they might be changing over time. - Did you undertake canopy sampling within your research?

Unfortunately, the answer is no. We focused on ground-level surveys of the vegetation and looked at the lateral movement/impact of freshwater insects from the stream into the forest. Insects do, obviously, also travel upwards too and it would have been great to include surveying at different heights within the forest, but we were limited by what could be achieved within the time frame and resources that were available. Canopy surveying can be complex and would have required more equipment, making it too expensive for us to undertake. - Do you think that humidity may have an influence on insect distance away from water?

This is something that was simply out of scope for my research project. I’m aware that humidity can impact the flying ability of some insect groups so it is important, and humidity may factor into the emergence times of some species. - Did you notice if the spiders that you found were mostly from a particular group?

We looked at the overall spider community, rather than breaking it down into families or species, so I can’t give you a definitive answer to this question. Again, it would have been great to look at this in more detail if we had more capacity. However, from my own personal observations, I can say anecdotally that some of the dominant groups in the tropics in our samples were sac spiders, tangle-web and jumping spiders. The long-jawed orb weavers are known to be specialists of aquatic prey so this was not necessarily what you’d expect so near water. In the UK, I was surprised at how spread out throughout the transects these specialist spiders were – rather than being concentrated near the water. I wonder if this could be to do with the fact that the UK forests were more open and managed. - Did you consider eutrophication and the oxygen levels within the streams?

We didn’t measure oxygen levels within any of the streams, but we know that this can be important so we tried to standardise this variable by only using streams that were in some kind of protected area, in the hope that these would be less likely to suffer from eutrophication.

Literature references

- Nash et al (2023) Latitudinal patterns of aquatic insect emergence driven by climate: https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13700

- Nash et al (2021) Warming of aquatic ecosystems disrupts aquatic–terrestrial linkages in the tropics: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13505

- Al-Jaibachi et al (2018) Up and away: Ontogenic transference as a pathway for aerial dispersal of microplastics: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0479

- Armitage et al (1995) The Chironomidae: biology and ecology of non-biting midges. Springer Science & Business Media https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=DHPyCAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR10&dq=The+Chironomidae:+biology+and+ecology+of+non-biting+midges+armitage+the+behaviour+of+adults&ots=QVZOM3nfQH&sig=hZoSsR2GF4i555QMSms78RCTMO4

- Baranov et al (2020) Complex and nonlinear climate-driven changes in freshwater insect communities over 42 years: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13477

- Castro-Rebolledo and Donato-Rondon (2015) Emergence patterns in tropical insects: The role of water discharge frequency in an Andean Stream: https://doi.org/10.1051/limn/2015011

- Corbet (1964) Temporal patterns of emergence in aquatic insects: https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent96264-1

- Corkumet al (2006) Timing of Hexagenia (Ephemeridae: Ephemeroptera) mayfly swarms: https://doi.org/10.1139/Z06-169

- Finn et al (2022) Spatiotemporal patterns of emergence phenology reveal complex species-specific responses to temperature in aquatic insects: https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13472

- Hallmann et al (2020) Declining abundance of beetles, moths and caddisflies in the Netherlands: https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12377

- Henschel (2004) ‘Subsidized predation along river shores affects terrestrial herbivore and plant success’, Food webs at the landscape level. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, USA, pp. 189–199.

- Knight et al (2005) Trophic cascades across ecosystems: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03962

- Lewis-Phillips et al (2020) Ponds as insect chimneys: Restoring overgrown farmland ponds benefits birds through elevated productivity of emerging aquatic insects: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108253

- Muehlbauer et al (2014) How wide is a stream? Spatial extent of the potential “stream signature” in terrestrial food webs using meta-analysis: https://doi.org/10.1890/12-1628.1

- Nummi et al (2011) Bats benefit from beavers: a facilitative link between aquatic and terrestrial food webs: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9986-7

- Paetzold et al (2011) Environmental impact propagated by cross-system subsidy: Chronic stream pollution controls riparian spider populations: https://doi.org/10.1890/10-2184.1

- Recalde et al (2016) Unravelling the role of allochthonous aquatic resources to food web structure in a tropical riparian forest: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12475

- Richmond et al (2018) A diverse suite of pharmaceuticals contaminates stream and riparian food webs: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06822-w

- Romero et al (2021) Pervasive decline of subtropical aquatic insects over 20 years driven by water transparency, non-native fish and stoichiometric imbalance: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2021.0137

- Siqueira et al (2008) Phenological patterns of neotropical lotic chironomids: Is emergence constrained by environmental factors?: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2008.01885.x

- Stepanian et al (2020) Declines in an abundant aquatic insect, the burrowing mayfly, across major North American waterways: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1913598117

- Twining et al (2018) Aquatic insects rich in omega-3 fatty acids drive breeding success in a widespread bird: https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13156

- Van Klink et al (2020) Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax9931

- Wagner et al (2021) Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023989118

- Walters et al (2008) The dark side of subsidies: Adult stream insects export organic contaminants to riparian predators: https://doi.org/10.1890/08-0354.1

- WWF (2022) Living Planet Report 2022 – Building a nature positive society: https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-GB/

Further info

- The Hoverfly Lagoons Project: https://hoverflylagoons.co.uk/

- Adult Caddis ID guide from the FSC: https://www.field-studies-council.org/shop/publications/adult-caddis-aidgap/

- Freshwater ecology training courses from the FSC: https://www.field-studies-council.org/courses-and-experiences/subjects/freshwater-ecology-courses/

- Aquatic Insects Special Interest Group from the RES: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/membership-and-community/special-interest-groups/aquatic-insects/

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is only possible due to contributions from our partners.

- Find out about more about the British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk/

- Browse the list of identification guides and other publications from the Field Studies Council: https://www.field-studies-council.org/shop/

- Check out environmentjob.co.uk for the latest jobs, volunteering opportunities, courses and events: https://www.environmentjob.co.uk/

- Check out the Royal Entomological Society‘s NEW £15 Associate Membership: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/shop/membership-and-fellowship/associate-member/