1-4 billion hoverflies migrate into and out of southern Britain each year. Despite the fact that these migratory insects help control pest species (such as aphids) and provide important pollination ecosystem services, migratory flies do not receive anywhere close to the same attention within research as migratory vertebrates such as birds, whales and turtles. An Exeter University study on insect migration is addressing this knowledge gap.

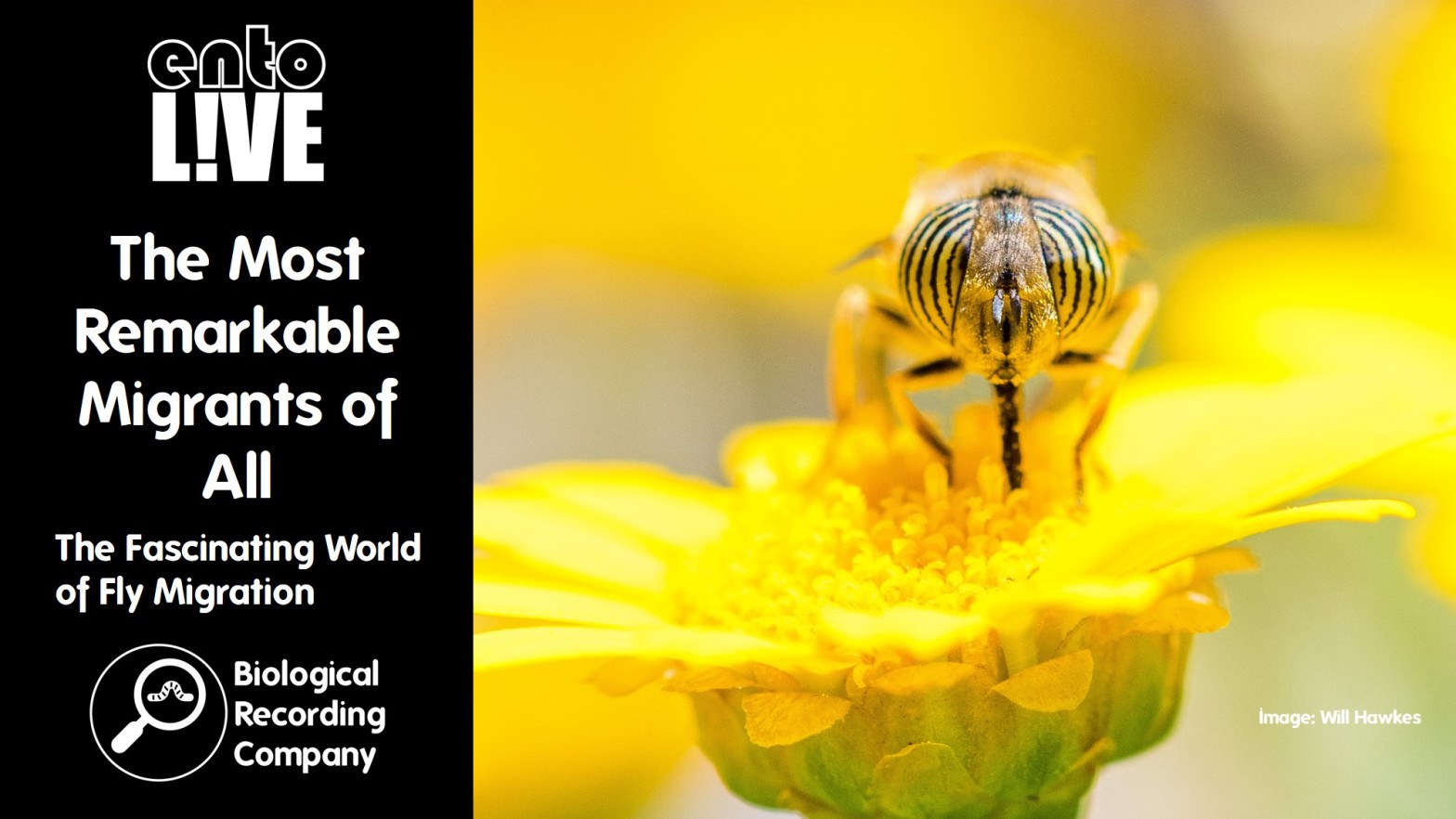

Dr Will Leo Hawkes is an insect migration scientist from North Wales, based at the University of Exeter. He travels to insect migration hotspots around the world to study this most remarkable of natural phenomena.

Q&A with Dr Will Leo Hawkes

Are you able to estimate the biomass of migratory flies?

Yes, it is possible – the two species of hoverflies which my supervisor recorded going over southern England recorded about 4 million which is 80 tonnes per year. We recorded all insects going through the Pyrenees and about 90% of those were flies. We estimated well over 100 tonnes of insects per year for the whole of the Pyrenees per year, based on the single pass that we monitored and scaled up. However, I think that our estimation is probably a big underestimate and I think the numbers and biomass are probably much greater.

Is there any evidence that some migratory flies “fatten up” before migration?

Yes – they get really fat with round bodies that look like they are about to burst! The autumn migrants are always so much bigger than the summer migrants. Migratory generation adults tend to be stronger flyers with better immune systems and improved visions – like little “super flies”! The development of a fly into a migratory fly is determined when they are third instar larvae and depends on the length of light in the day while in the third instar of development. If these specific conditions are present in the third instar, their genetics will shift and cause the development of a migratory adult.

What is known about current migratory fly numbers when compared to historical populations?

One really exciting study was undertaken in southwest Germany by Wolf Gatter. Hoverflies migrating through the mountains here were studied in exactly the same way for more than 40 years between 1978 and 2019. Terrifyingly they found that migratory aphid-eating hoverflies (like marmalades) have declined by 97%. This finding is likely mirrored across other sites like the Alps and the Pyrenees. Having been to these sites and seen how many insects fly through now, it’s actually hard to imagine that this is a fraction of what there used to be. The only bit of hope is that migratory flies have so many generations and may be able to recover quickly if the issues that are causing the declines are dealt with. The truth is that we have so little data on migratory flies that it’s hard to make overarching statements as what is happening in Germany may not be typical of other sites. This is why it is important to have systematic studies that are repeatable

Have you used the big dataset created by the UK Hoverfly Recording Scheme in your research?

In our Pyrenees study, we used the Hoverfly Recording Scheme data to find out when these migratory peaks occurred and compared this to data on lots of environmental variables to look for any correlations. We found that the best predictor of large-scale migration was increased autumnal temperatures (i.e. there were higher numbers coming through during warmer autumns). This dataset is an amazing resource and so useful, with fellow researchers using the data extensively to better understand hoverflies. This is why it is important that biological recorders and the general public submit their hoverfly records to iRecord (preferably with a photo). There are some great ID resources out there too, such as Steven Falks’s hoverfly Flickr albums and Britain’s Hoverflies WILDGuide.

What do locust blowfly larvae eat when in the UK?

The Locust Blowfly (Stomorhina lunata) mostly lay its eggs in locusts, but may be laying its eggs in native Orthoptera found in the UK. Most migratory species tend to be generalists rather than specialists and are often flexible with their behaviours.

Did you use tech such as image processing or AI to count the flies from the video frames?

I’d love to be able to tell you it was all automated – that would have made my job so much easier. We tried so hard to make it automatic but because of the strong winds there was too much movement and it had to be done by manually. It took forever and I had many long days in a dark room counting the flies in each frame of the footage! For each sampling trip, I’d have a couple months in the Pyrenees in the sun, followed by just over a month of counting flies from the footage and another month of identifying the flies that we caught in the lab.

Is it understood why the return journey is in one generation?

It’s not understood entirely but I think it’s because in autumn everything starts dying off so it makes more sense in terms of energy to make the long trip to an area where there is a lot more food available. Flies are quite flexible and if we experience an Indian summer and there are plenty of flowers still blooming they will stay around a bit longer.

Does the large investment that goes into migration make migratory insects more prone to population decline and extinction in the event of man-made or natural catastrophic events?

Most migratory species are generalists in nature and so can survive on a wider range of foods than specialists. This actually tends to make them quite flexible when faced with difficult conditions. This doesn’t mean they are immune to risk and pesticides are known to be a problem. Specialist species, such as the Pine Hoverfly (Blera fallax) that will be featured in an entoLIVE later this month, are much more at risk as they are less mobile. A single Drone Fly (Eristalis tenax) lays about 200-400 eggs, with the survival rate for individual flies relatively low. Many of these flies will die because they fly off in the wrong direction and it is only the ones that make the big journeys to the correct place that will survive.

Were the flies on Marion Island known to be there previously or was this an accidental finding?

I think it was purely accidental. Some researchers went to the island and identified some good spots to sample flies and set up Malaise traps (flight interception traps that look like a tent). The migratory blowflies just happened to be passing at that time and were found in the traps!

How do you know how many generations complete the various legs of the journey?

There is still a lot we don’t know. What we do know, we know from general observations and citizen science projects, such as when there is an influx of a particular species. Butterfly migrations are better understood than other insect groups and have been used as a proxy for a lot of fly migration work. It would be great if we could put little trackers on the backs of these insects and work out where they go (and how far they go) in the spring. The spring and autumn migrations are completely different from each other, with the big autumn migrations being mostly females and the spring migrations being an approximately 50/50 split. I’ve also only ever seen the pathogens (the fungi coming out of the bodies) on the spring migrants and I think this is probably due to them spending longer in certain places or having more generations (or just the males are more prone to infection). It really is a wonderful field of study to be part of as it is only just beginning and i can probably count on my hands the number of people looking at insect migrations. There is still huge voids in our geographic knowledge of insect migration, such as in South America and Western Asia. We need more fly migration researchers.

Can flies be said to be gregarious in migrating, like locusts?

This is a question I really want to answer with a study. We don’t really know but when I was in Cyprus we had hundreds of thousands of dragonflies just appear one day. They were swarming around and eating the flies and other insects and then they just left. Then a few days later we saw a group of similar numbers heading back the opposite way. This has also been reported anecdotally from Borneo with distinct groups of migrating dragonflies. I suspect that if any insect is going to display this social behaviour it is most likely to be dragonflies. Flies don’t arrive in swarms, but they do arrive at peak times together and it kind of makes sense for them to arrive together for mating. I’d like to see more work into the possibility of social behaviour in flies.

While using the flight simulator to quantify the hoverfly’s flying direction, what criteria did you set up to identify the fly as a migrant?

We caught the flies as they were flying through a mountain pass nearly 2300m up in the Pyrenees. They were all heading south and there is simply not enough habitat up in this location for the hoverflies to exist if they were doing anything but passing through.

Could it be that where there are concentrations of insect-eating birds there will be more insects then?

No one has direct evidence for this yet, but I’m sure that the birds will use concentrations as fuel. Birds are clever too and so I’m sure they can target the insects year after year. In fact, the amur falcons which migrate across the Indian ocean are thought to do so because they are following globe skimmer dragonflies which do the same migration!

How does a hoverfly fly?

A great question, they’re amazing fliers, they flap their wings so fast which allows them to hover. They are also incredibly efficient fliers, using barely any energy as they fly as they can burn fat directly to turn into fuel. Rather than having to break the fat down first like us humans have to do.

Where does your interest in flies come from?

I’ve always adored insects, ever since I was very little crawling around the garden insects were the subject of my curiosity. They were much easier to catch than birds, and didn’t bite as hard as a badger! I think flies are just so fascinating and they have so many stories to tell. I feel very lucky to be able to tell a few of them to human ears.

Literature references

- Doyle et al (2020) Pollination by hoverflies in the Anthropocene: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2020.0508

- Massy et al (2021) Hoverflies use a time-compensated sun compass to orientate during autumn migration: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2021.1805

- Hawkes et al (2022) Migratory hoverflies orientate north during spring migrationn: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsbl.2022.0318

- Hawkes et al. (2022) Huge spring migrations of insects from the Middle East to Europe: quantifying the migratory assemblage and ecosystem services: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ecog.06288

- Finch and Cook (2020) Flies on vacation: evidence for the migration of Australian Syrphidae (Diptera) https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/een.12856

- Hu et al (2016) Mass seasonal bioflows of high-flying insect migrants https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aah4379

- Nabeshima et al (2009) Evidence of frequent introductions of Japanese encephalitis virus from south-east Asia and continental east Asia to Japan https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/jgv/10.1099/vir.0.007617-0

Further info

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2026

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is only possible due to contributions from our partners and supporters.

- Find out about more about the British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk/

- Check out the Royal Entomological Society‘s NEW £15 Associate Membership: https://www.royensoc.co.uk/shop/membership-and-fellowship/associate-member/

3 thoughts on “The Most Remarkable Migrants of All: The Fascinating World of Fly Migration”