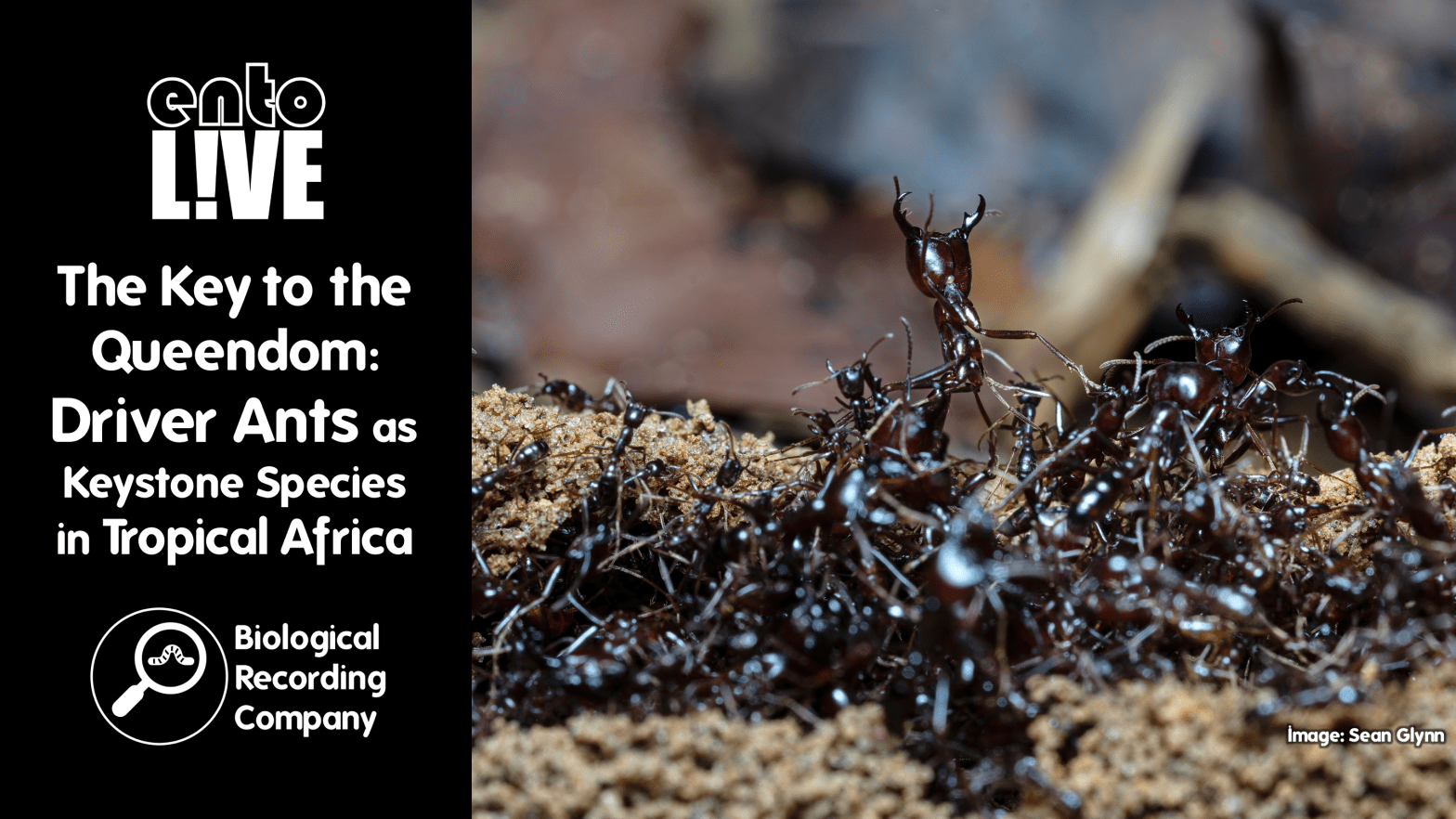

Driver ants form some of the most impressive colonies of any animal on Earth, up to 20 million strong. They form vast raids to capture their prey but surprisingly little is known about them. This talk explores what we know about driver ants and what we’re beginning to learn about this amazing group of social insects using cutting-edge modern tools.

Q&A with Dr Max Tercel

Max Tercel is a scientist studying the ecology of ants. He is interested in how ants affect the world around them and uses time-tested entomological techniques as well as newer cutting-edge molecular methods, such as DNA metabarcoding, in his research.

1. Do the two species of Dorylus in tropical Africa predate each other?

No, as soon as they see each other they immediately go in opposite directions. This is also true of encounters between different colonies of the same species. This behaviour makes sense. On a chance encounter between representatives of two colonies, each individual has no way of knowing how big the other’s colony is. It could be huge! The risk to reward ratio of interacting with the other species is heavily weighted towards risk. driver ants are ferocious – they are certainly not easy prey. It therefore makes sense for them to have evolved to steer totally clear of one another. Whilst much remains unknown about these ants, one of the things that we do know is that driver ant movement ecology is heavily determined by proximity to the nearest neighbouring colony.

2. What castes exist within Driver Ant colonies, and do these castes play different roles within raids?

Driver ant workers come in two or three distinct ‘morphs’ in terms of size. In other words, most workers tend to fall into one of two/three general size categories. There are also intermediate individuals who fall between these size classes, however. The largest workers are called supermajors. They have giant heads with large piercing mandibles, evolved for defence, and position themselves along the margins of a raiding party column, so protecting the other ants. The smallest workers – so-called minor workers – look more conventionally ant-like, with smaller heads and cutting mandibles. They can be found at the front of an advancing raid party, squeezing in amongst small gaps in the leaf litter and rooting any other animals out.

3. You mentioned there are other animals – e.g. beetles, flies, springtails, birds – associated with driver ant colonies. How come the driver ants leave these species alone, when they so ferociously attack everything else?

This is a really interesting question. And funnily enough, it is something we are already planning to investigate during the 2026 field season, using behavioural experiments. As a general rule, from my personal experience, it seems that most of the driver ant associates pass amongst the colony ‘without trace’. They are effectively invisible. This is just my personal observation though. The question is yet to be empirically researched. It will be exciting to see what we find next year – watch this space!

4. How do you manage to protect yourself from the ants whilst studying them!?

You get bitten all the time! Even if you avoid the actual raids, there are always driver ants in the leaf litter samples we collect, and they have a real knack for scurrying out of the sample and onto your body and giving you a nip. I do have a boiler suit that I wear sometimes, but this is only bearable when it’s a relatively mild day in the forest. More often I just take five minutes every now and then to pick the ants off myself after a round of sampling. It’s part of the job.

5. Last week we had an entoLIVE talk from Professor Elva Robinson focused on the Shining Guest Ant. This is a species which lives within the nest of much larger wood ants. Are there any ants with similar lifestyles living within Driver Ant colonies?

I highly suspect so. Again, no formal research here yet, but I think we’ve found at least one species – in the genus Pheidole – which seems highly associated with driver ant refuse piles. I’ve also seen them often around the edges of raid columns and sometimes also near on or the nests. It is also possible there are commensal ants within the driver ant nests, but I’ve not had a chance to see inside one.

6. Do driver ants always raid along the same routes?

This is one of the central questions being addressed by my research team. Generally, we think that driver ants tend not to raid in the same place multiple times, but they do sometimes. I have seen driver ants raid the same place three times in a week before, but this is a rarity. More often they tend to explore semi-randomly in all directions from the nest. We do not know what influences the decision to choose a particular direction and route to raid. Many of our assumptions of the biology and ecology of driver ants are based on understanding of similar army ants in South America. In these South American ants, it is known that the colonies raid in a highly ordered and efficient – almost mathematical – pattern. Driver ants seem to be more random.

Literature References

- Savage (1847) ‘I. On the habits of the “drivers” or visiting ants of West Africa’: https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1847.tb01686.x

- Gotwald Jr (1978) ‘Trophic ecology and adaptation in tropical old world ants of the subfamily Dorylinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)’: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2387902

- Mody et al. (2003) ‘Determinants of small-scale mosaics of arthropod communities in natural and anthropogenically disturbed habitats’: https://www.bgbm.org/BioDivInf/Biolog/Statusseminar1/StatusReport202001.pdf#page=136

- Schöning et al. (2005) ‘Temporal and spatial patterns in the emigrations of the army ant Dorylus (Anomma) molestus in the montane forest of Mt Kenya’: https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0307-6946.2005.00720.x

- Schöning et al. (2007) ‘Prey spectra of two swarm-raiding army ant species in East Africa’: https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00360.x

- Peters et al. (2011) ‘Deforestation and the population decline of the army ant Dorylus wilverthi in western Kenya over the last century’: https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.01959.x

- Van Huis et al. (2021) ‘Cultural aspects of ants, bees and wasps, and their products in sub-Saharan Africa’: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s42690-020-00410-6.pdf

- Gotwald (1995) ‘Army Ants: The Biology of Social Predation’

- Kronaeur (2020) ‘Army Ants: Nature’s Ultimate Social Hunters’

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk