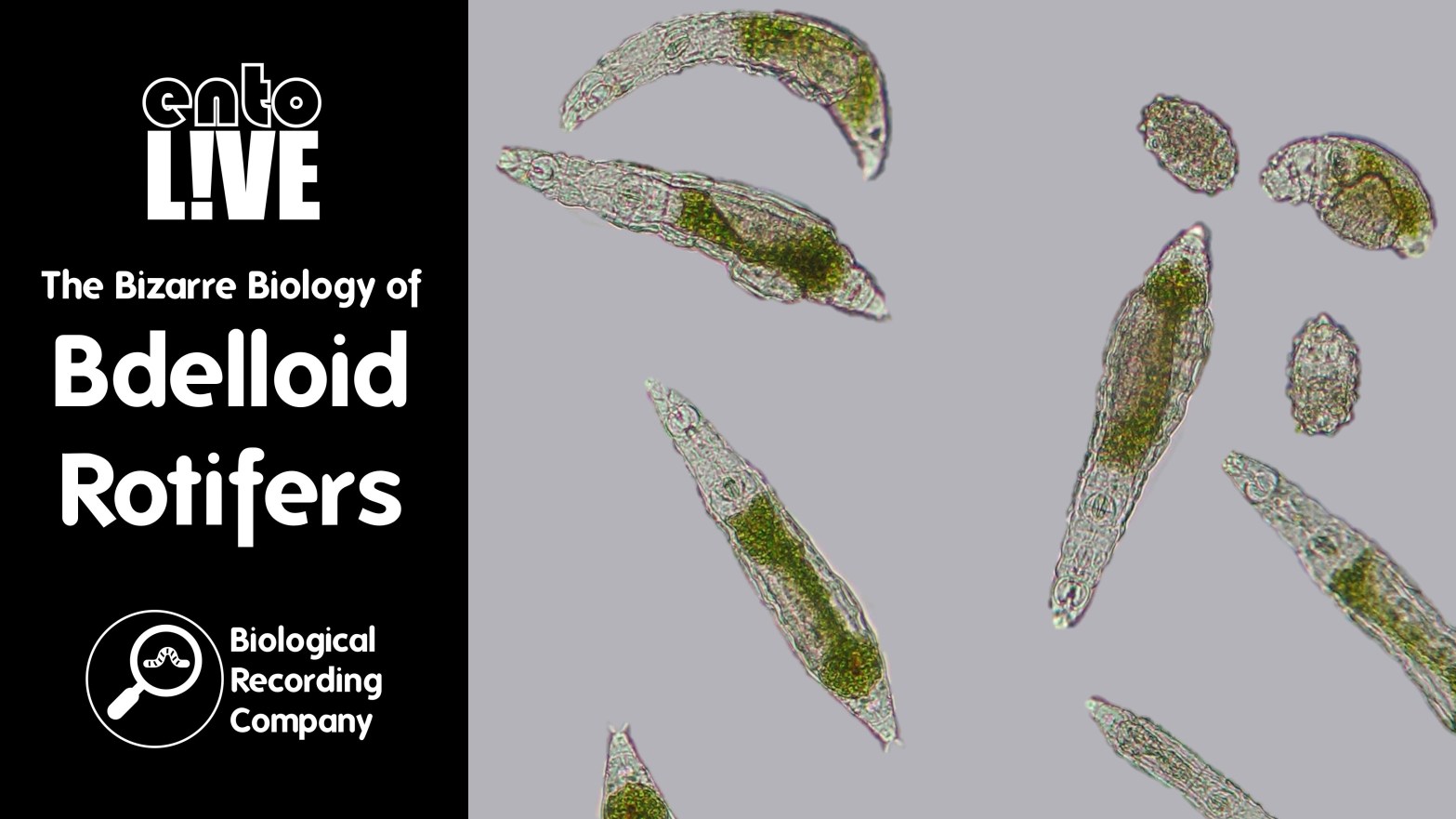

Bdelloid rotifers are tiny filter-feeding animals that live in freshwater habitats worldwide: in ponds, streams and lakes, even where the water sometimes dries up or freezes, like moss, soil, puddles and ice sheets. They are among the most resilient of all animals, and also have some of the strangest biology.

Unlike other known animals, all bdelloid rotifers are females, with no sightings of males in the 300 years since they were discovered — rotifer mothers lay eggs that hatch into genetic copies of themselves, without sex, sperm or fertilisation.

Another surprise is that bdelloid rotifers have been stealing DNA from other organisms on a massive scale by a process called horizontal gene transfer, so that about one in ten of their genes have been copied from different kinds of life, including bacteria, fungi and even plants.

Among these stolen genes, we recently discovered that bdelloid rotifers have copied dozens of recipes for antibiotics from bacteria, which the rotifers now use to fight off their own diseases. This unusual defensive strategy could lead to short-cuts in the race to develop new drugs against antibiotic-resistant infections in human patients, and might also shed light on the strangely sexless lifestyle of these animals.

Q&A with Dr Chris Wilson

Dr Chris Wilson is a Lecturer in Biology at the University of Oxford. Originally from Kent, he completed undergraduate studies at St Anne’s College and a doctorate at Cornell University in the USA before returning to the UK, where he has held research fellowships and teaching positions at Imperial College London and St Hilda’s College, Oxford. He is interested in the causes and consequences of sexual versus asexual reproduction, which he addresses by studying the evolution, ecology and genomics of microscopic freshwater rotifers and their natural enemies, particularly pathogenic fungi.

1. If rotifers reproduce asexually, how do scientists define species?

We usually think of a species as a group of organisms that are capable of reproducing to produce fertile offspring. It turns out that even though rotifers don’t reproduce sexually, it is still possible to robustly define them into discrete species. First and foremost, this can be done based on morphology. Namely, there are consistent, clustered morphological forms which exist within the diversity of rotifers. These clustered forms are distinct from one another – it’s not just a continuous spectrum of variation. We think these discrete forms arise because the environment selects for particular shapes of rotifers’ body parts (e.g. their so-called ‘teeth’ and ‘toes’). The most suitable of these morphological forms are then preserved under natural selection. For greater precision, or as a supplement to the morphological species concept, DNA can be used. Sequencing of bdelloid rotifer DNA has corroborated that there are indeed distinct, clustered genetic sequences within the broader spectrum of variation, matching what we might generally refer to as species.

2. You mentioned rotifers stealing genes from bacteria, protists and plants. Do they also steal genes from other animals?

It’s a great question. It’s very hard to tell if rotifers have been stealing genes from other animals. In contrast, plant DNA, for example, sticks out like a sore thumb amongst the genome of a rotifer – it is clear it doesn’t belong there. Other animal DNA, if hidden amongst a rotifer’s genome, would be much less obvious. We would love to look more closely at this question. My personal guess, for what it’s worth, is that bdelloid rotifers are almost certainly stealing genes from other animals. A harder, follow-up question, would be which genes are being stolen, and what are these new genes doing?

3. How hard is it to identify rotifer species?

Generally, it is very difficult. For a start, bdelloid rotifers are soft-bodied, which means that their body parts (particularly the so-called ‘wheel organs’) are often tucked away internally and not visible. It is these body parts which are essential to view for species identification. In practice, this means you must be fast, i.e., make every effort to minimise the time taken between extracting a sample containing rotifers in the field and viewing it under the microscope in the laboratory. Preserving rotifers is an even harder job because as soon as they are disturbed they contract, hiding their characteristic features internally. The only identification key for rotifers is in German and is around 50 years old, which adds another challenge. There are only a handful of people around the world who are really good at identifying bdelloid rotifers to species level. Some of the other rotifer groups with harder bodies are more easily identified.

4. Has the process of horizontal gene transfer generally been consistent within species?

Yes, generally it has been. This is because most of the horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers occurred a very long time ago. Horizontal gene transfer in rotifers is not quick; we estimate that it tends to happen only around once every 100,000 years. Rotifers have, of course, been around for several millions of years so over this time they have nevertheless accumulated a lot of so-called ‘foreign’ genes. Indeed, horizontally gained genes make up around 10% of bdelloid rotifer genomes, i.e., 1 in 10 bdelloid rotifers genes isn’t even an animal gene! Because of how slow this process is, many bdelloid rotifer species share the same horizontal genes which arrived hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of years ago. But, simultaneously, there are handfuls of genes which are unique to particular species and therefore have arrived more recently. These clusters appear to be consistent amongst individuals within a species.

5. How exactly does horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers work?

We don’t know! One of the great problems of horizontal gene transfer in rotifers being so rare (occurring once every 100,000 years or so) is that nobody has actually witnessed it happen. Several scientists have tried to make rotifers ‘eat’ DNA to see if it is copied into their genome, but none has seemed to stick. There are various hypotheses as to how the process works. One theory is that during desiccation, the rotifers’ genome becomes damaged, and may, during the repair stage, incorporate new genes from surrounding environmental DNA. The issue with that theory is that there are bdelloid rotifers which do not survive desiccation which still have horizontal genes. An alternative hypothesis is that it’s to do with ‘jumping DNA’ – pieces of DNA which can jump from one place in the genome to another, and perhaps even transfer from one organism to another. But while lots of animals have jumping DNA, only the rotifers have gained thousands of genes horizontally. For now, it’s a mystery, but it’s a really active research area in this field, and we’d love to know the answer in the future.

Literature References

- Wilson et al. (2024) ‘Recombination in bdelloid rotifer genomes: Asexuality, transfer and stress’: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168952524000283

- Wilson and Sherman (2010) ‘Anciently asexual bdelloid rotifers escape lethal fungal parasites by drying up and blowing away’: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1179252

- Wilson et al. (2024) ‘Tiny animals use stolen genes to fight infections – and could fight antibiotic resistance too’: https://theconversation.com/tiny-animals-use-stolen-genes-to-fight-infections-and-could-fight-antibiotic-resistance-too-234737

Further Info

- Örstan and Plewka (2017) ‘An introduction to bdelloid rotifers and their study’: https://www.quekett.org/starting/microscopic-life/bdelloid-rotifers-old

entoLIVE

entoLIVE webinars feature guest invertebrate researchers delving into their own invertebrate research. All events are free to attend and are suitable for adults of all abilities – a passion for invertebrates is all that’s required!

- Donate to entoLIVE: https://www.gofundme.com/f/entolive-2025

- Upcoming entoLIVE webinars: https://www.eventbrite.com/cc/entolive-webinars-74679

- entoLIVE blog: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk/category/entolive-blog/

- entoLIVE on YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLuEBNUcfMmE95Re19nMKQ3iX8ZFRFgUAg&feature=shared

entoLIVE is delivered by the Biological Recording Company in partnership with the British Entomological & Natural History Society, Royal Entomological Society and Amateur Entomologists’ Society, with support from Buglife, Field Studies Council and National Biodiversity Network Trust.

Check out more invertebrate research, publications and events from the entoLIVE partner websites:

- Amateur Entomologists’ Society: https://www.amentsoc.org

- Biological Recording Company: https://biologicalrecording.co.uk

- British Entomological & Natural History Society: https://www.benhs.org.uk

- Royal Entomological Society: https://www.royensoc.co.uk